Reading time: 7 minutes

On July 25 1882, Inspector Frederick Secretan, the head of Victoria Police’s Detective Branch, shifted uncomfortably in his seat. In the wake of the Kelly Gang fiasco, during which Ned’s infamous band of outlaws had managed to elude the police until the bloody shootout at Glenrowan, a royal commission had been called to inquire into Victoria’s police force. Secretan’s detectives had been singled out for particular criticism. Now, as he fronted the commissioners, the inspector sought to explain the methods he deployed for detecting crime in Melbourne and across Victoria.

By Benjamin Wilson Mountford, Australian Catholic University

The anxiety and sense of impending chaos that accompanied the 1850s gold rushes had led to the early adoption of plain-clothes policing in colonial Victoria. Unlike in Britain, where detectives were discouraged from wearing plain clothes and liaising with criminals, Melbourne’s gumshoes were to move across the colony, detecting crime and weeding out offenders. Lacking scientific modes of inquiry, they relied on their ability to conduct surveillance and to establish relations with informants, or “fizgigs”.

By the 1880s there were 28 detectives in the colony. Seven were based in country districts, one serviced the post office, four were clerks and 16 were deployed on outdoor duty across Melbourne. The metropolitan force, Secretan explained, divided the city into spheres of influence, with the numbers of detectives apportioned accordingly. Ideally, Secretan suggested to the commissioners, 38 detectives would be deployed across Victoria, “including one Chinese”.

Secretan’s Chinese detective, and one of the men who had been briefly involved in the hunt for the Kelly Gang, was Detective Fook Shing.

Like tens of thousands of his countrymen, Fook Shing had journeyed from China to Australia during the gold rushes of the 1850s. Leaving troubled Guangdong, via the British ports of Hong Kong and Singapore, he appears to have arrived at South Australia (probably to avoid the poll tax implemented to deter Chinese arrivals at Melbourne) and to have walked overland to the goldfields.

On the Bendigo diggings, Fook Shing served the colonial government as a local “headman” (a “Chief of the Chinese” as he put it) and took a leading role in community life – being active in Chinese societies, running a successful theatre and brickworks. Wealthy, connected and well represented in court, he kept a pistol under his pillow for when extra-legal methods were required to protect his followers.

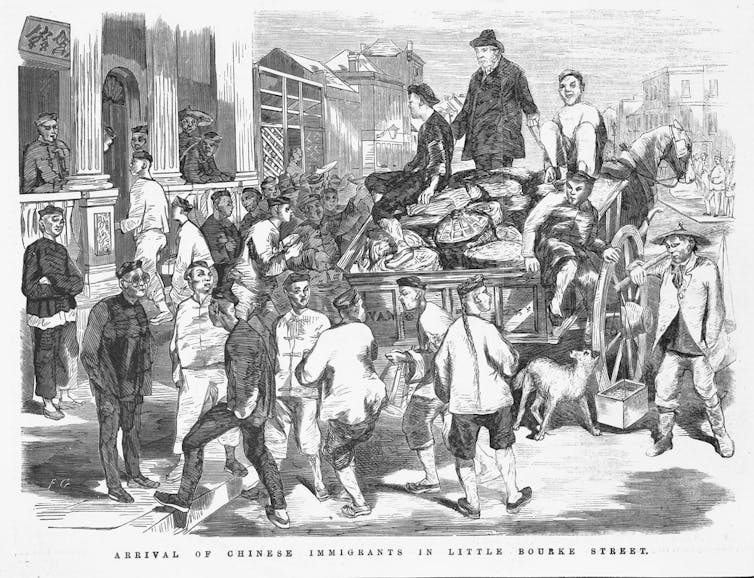

For the (heavily Irish) Victorian police force, who relied on interpreters of mixed quality, were befuddled by Chinese names and struggled to identify Chinese criminals, men like Fook Shing proved invaluable on the goldfields. During the 1860s, as the Chinese in Victoria increasingly left the gold country and congregated in Melbourne, particularly around the city’s growing Chinatown in Little Bourke Street, Fook Shing was formally appointed to the Victoria Police.

For the next 20 years, Fook Shing served as Melbourne’s Chinese detective. From his home, just off Little Bourke Street, he policed the Chinese community and visitors to the area. Among his colleagues he was regarded as a “trustworthy member of the service” who could “always be relied upon” and impressed with his “intimate knowledge of the Chinese criminal class” in Melbourne.

This support was mirrored up the chain of command. Superior officers paid tribute to his performance in the line of duty and awarded a number of gratuities in acknowledgement of service.

But the work of the Chinese detective was hardly confined to Melbourne. Fook Shing could regularly be found on assignment in country Victoria. There he was given “every facility” by local authorities, who (in the words of one goldfields constable) found him “in a position to give all necessary information and point out any further steps” for tracing Chinese criminals.

Word of his arrival in country towns spread quickly among local Chinese criminals and suspects. In 1875, for instance, the Chinese detective asked the murder suspect An Gaa: “You know Fook Shing?” The accused replied that he did, having been warned of the detective’s impending arrival by his fellow Chinese prisoners in Castlemaine Jail.

‘A civilised specimen’

At much the same time, Fook Shing served as guide for colonial and foreign observers seeking to understand the Chinese and their coming to Australia. “We need no magic horse or flying carpet to take us into China,” the great colonial author and journalist Marcus Clarke reflected in 1868.

All we do is turn down Little Bourke-street and our friend F – S –, once a Mandarin, now a distinguished member of the detective force, will point out to us the ‘manners and customs’ of his countrymen.

A decade later, in a two-part feature entitled “Melbourne Illustrated”, the London Graphic illustrated newspaper surveyed all the usual marks of colonial progress: the port, the commercial exchange, the university, the public library and gardens, and (of course) the racecourse.

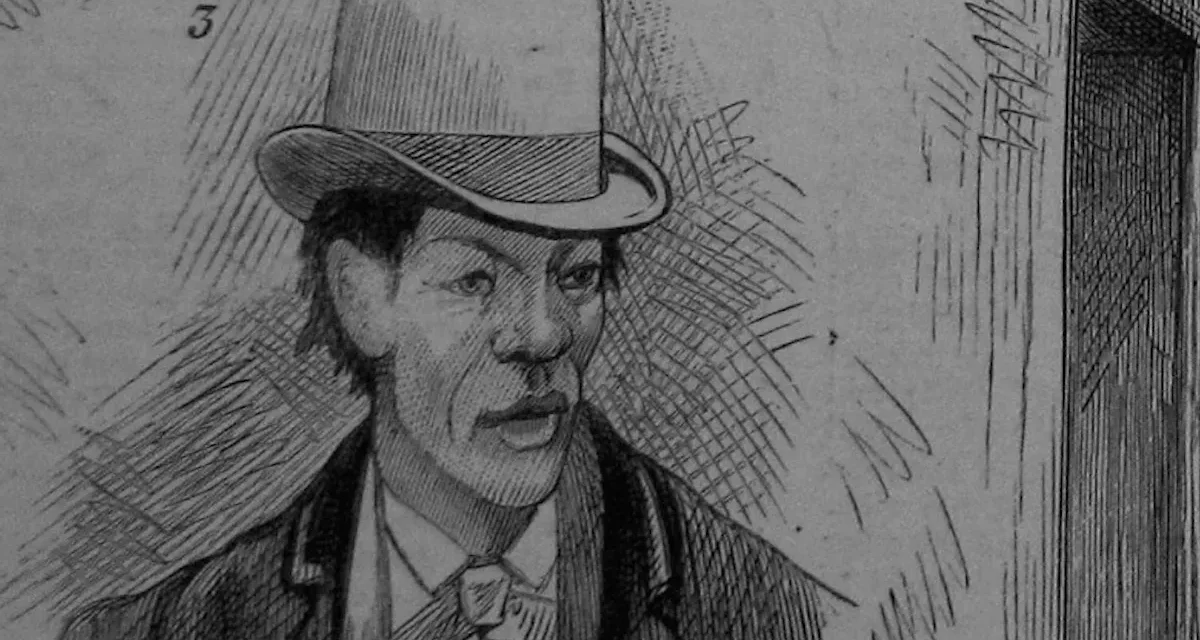

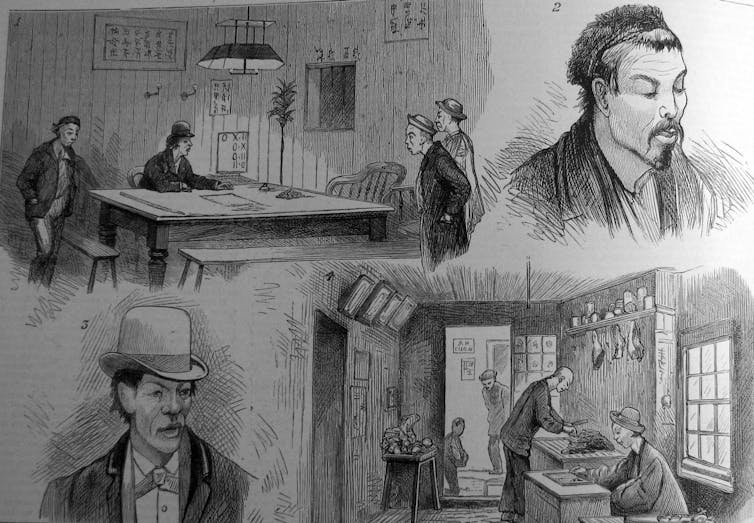

Finally came a reflection on the “Anti-Chinese Movement” and a visit to Chinatown. “The Chinese question is the topic of the day”, the author informed his metropolitan audience, reflecting on the strong racial anxiety that the presence of the Chinese in Australia had evoked since the gold rushes, “and it may interest you as well as the Australians … We had as our guide Fook Shing, the Chinese detective, whose portrait I have taken as being a civilised specimen of a Chinaman.”

But just as he was etched into contemporary impressions of colonial Victoria, Fook Shing also confronted anti-Chinese racism and discrimination. Despite his impressive record over 20 years, and in contrast to a number of less accomplished white colleagues, the Chinese detective was never promoted above his entry rank of detective third class.

Opium and information

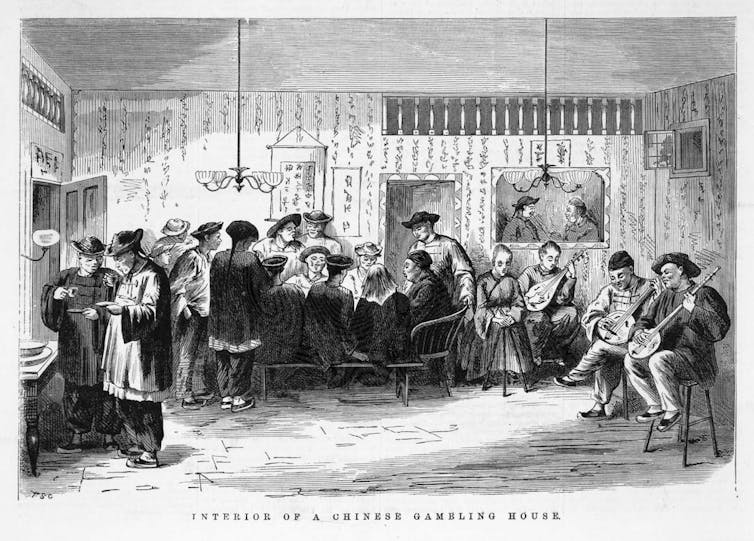

At times he endured poor relations with both uniformed policemen and fellow detectives. Colonial newspapers, meanwhile, regularly critiqued his gambling and his opium smoking, reporting his appearance in the gambling houses and opium dens that grew up along Little Bourke Street to service the community. “The Chinese Detective”, The Age declared in January 1873, while complaining about the lenient sentences being handled out to illegal Chinese gamblers, is “himself an inveterate gambler”.

While they disliked the sensational media attention, Fook Shing’s superiors were rather less concerned by these apparent moral failings. In fact, they quietly accepted them as essential to policing the Chinese – and helped to pick up the tab. After interrogating An Gaa, for instance, Fook Shing submitted a receipt for funds “spent obtaining information”.

“The amount charged,” Secretan noted when organising Fook Shing’s reimbursement, “is principally for opium supplied to the Chinese … I know opium is necessary to obtain anything from the Chinese at all.”

On occasion, Fook Shing appears to have carried his investigations beyond Victoria. In October 1875 the Chinese detective travelled to Sydney in pursuit of Ah Hon for “larceny of opium” and successfully ensured the offender was committed for trial.

While it was quietly approved by the Victoria Police’s top brass, Fook Shing’s drug use eventually took a heavy personal toll. By the 1880s, his health declining, he was utilised as an interpreter, before eventually being retired unfit for further service in 1886. A decade later, having anglicised his name, Henry Fook Shing was laid to rest in Melbourne Cemetery.

In recent decades, the importance of Australia’s commercial relationship with China and increasing migration from China to Australia have helped to spark renewed interest in the historical links between the two countries. As stories like Fook Shing’s remind us, colonial Australia was not simply an outpost of Britain, it was also a society intricately connected to China.

Towards the end of the 1850s, perhaps as many as one in five men on the Victorian goldfields was Chinese; by the end of the 19th century Melbourne’s Chinatown was among the most well-known in the world.

As he trawled the streets of Marvellous Melbourne and traipsed across the countryside on behalf of the Victoria Police, Fook Shing played a vital role in mediating between the colonial state, white settlers and the first generations of Chinese migrants to arrive in large numbers and to make their homes in Australia.

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Articles you may also like:

North Africa in WWII: Total War with Honour?

Reading time: 7 minutes

The North African campaigns during the Second World War have a reputation for being “clean” wars, free from the atrocities we see when studying the Eastern front or the Pacific theatre. However, when we look a little more closely, we can see this romanticized image is a little tarnished in places; we’ll take a look at what the historical record can tell us, as well as some details shared by Australian veterans of the conflict.

Weekly History Quiz No.271

1. When was the first Sino-Indian War?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

39th Militia Battalion and the Kokoda Track – Part 2

Reading time: 10 minutes

After the retreat from Kokoda, the battered survivors of B Company, 39th Battalion regrouped at the small village of Deniki. Major Allan Cameron, a 30th Brigade staff officer, arrived shortly after at Deniki on 4th August. Disgusted by the apparently ‘unsoldierly’ appearance of B Company, he jumped to the conclusion that these men must have run away from the fighting and had abandoned Kokoda for no reason. He sent them further back to Isurava in disgrace, depriving the remainder of the 39th of the only troops with battle experience. This wouldn’t be the last time that a textbook tactical withdrawal would be mistaken for cowardice. Cameron then decided that Kokoda must be recaptured.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.