Reading time: 14 minutes

From August 1914 to November 1918, over 416,000 men served in Australian forces fighting the First World War, in theatres ranging from the Pacific to the Middle East and France. 60,000 died far from home in battles fought thousands of miles away. But soon after the war began, one of the few instances when the fighting came home to the continent occured.

By Morgan W. R. Dunn

Spurred by professional frustration, bitterness at imperial racial politics, and a fateful call to arms from the Ottoman capital, Gool Badsha Muhammad and Mullah Abdullah, men from the fringes of Outback society, carried out a gruesome assault on hundreds of unarmed civilians. The aftermath brought riotous mobs, harsh new conditions for German, Austrian, and Asian residents, and a fresh shock to the country as the worst of the war years loomed.

Broken Hill: New Year’s Day, 1915

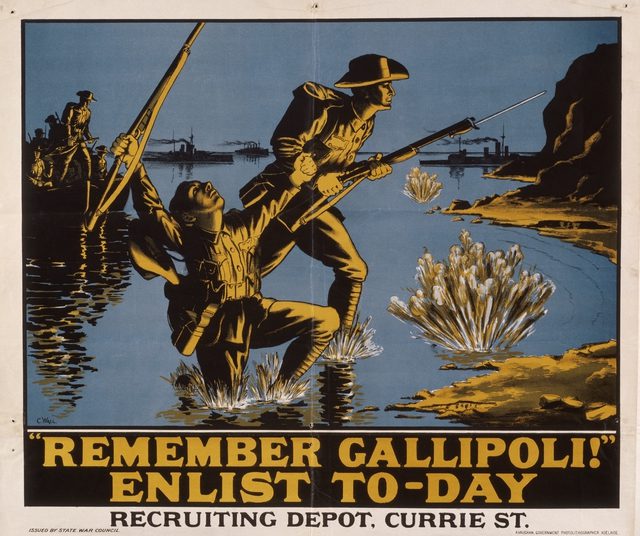

New Year’s Day, 1915 was a bright one. At the height of the southern summer, the weather was clear and warm. The national mood in Australia was still fresh, unaffected by the still-new war on the other side of the world, with Australian forces not yet engaged at the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey and the public none the wiser as to what was really happening.

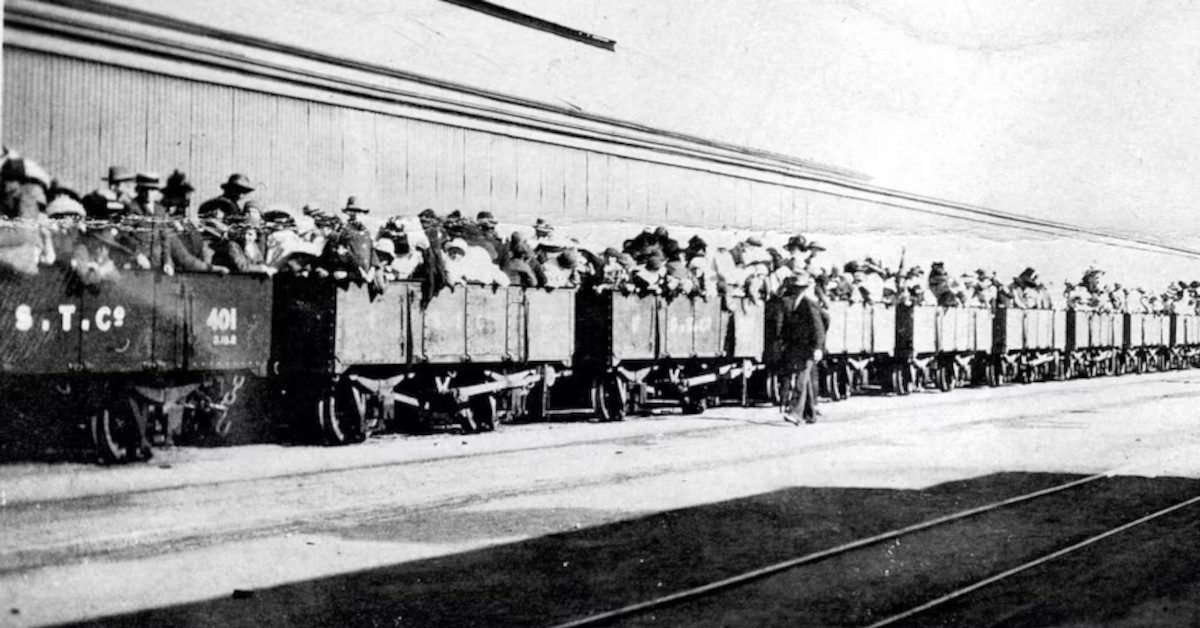

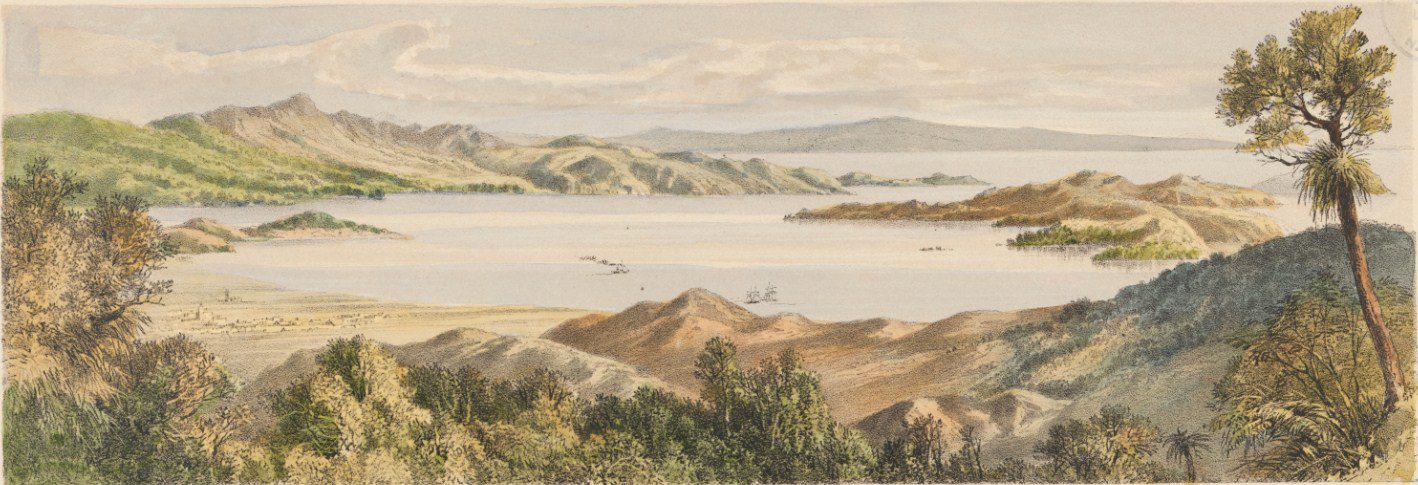

On such a fine day, a celebration of the new year seemed well in order. In Broken Hill, New South Wales, the local chapter of the Manchester Unity Independent Order of Oddfellows (MUIOO) fraternal organisation had arranged with the Silverton Tramway Company to supply a special train to carry 1,200 holiday makers of all ages from Sulphide Street Station to nearby Penrose Hill in Silverton for a picnic.

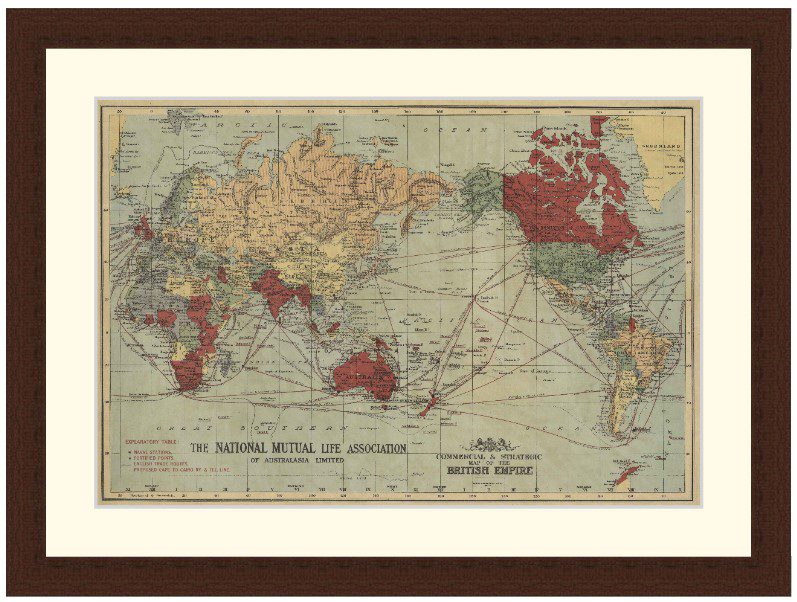

The picnickers represented the white, English-speaking population of Broken Hill, then a bustling, prosperous silver mining town. But they were not the only inhabitants of the area. Since the 1860s, the interior of Australia had relied on camel drivers from Afghanistan and British India to transport goods. Residing in “Ghantowns,” their own districts near Outback settlements, these “cameleers” provided a vital link to major cities and transport hubs.

But in November 1914, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V directed the Sheikh al-Islam, his religious representative as Caliph, Ürgüplü Mustafa Hayri Efendi, to issue a call to jihad, or holy war, for Muslims across the world. It was an attempt to leverage the Sultan’s position as Caliph, or foremost Muslim leader, in the Ottoman Empire’s contribution to the alliance of the Central Powers.

Mehmed hoped that it would particularly rile the Muslims of British India to rebel against Britain, and although it largely failed in that aim, it did reach the ears of many men on the fringes of the Muslim world. Two of these men, Gool Badsha Muhammad and Mullah Abdullah, were among the cameleers in New South Wales on the first day of 1915.

Who Were Gool Badsha Muhammad and Mullah Abdullah?

Gool Muhammad and Mullah Abdullah were representative of the often ignored underclass which made the British Empire function. Born into the Pashto-speaking Afridi tribe around 1874 in Tirah region of the North-West Frontier of India, an area in the mountainous border between modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, Gool Muhammad came to Australia as a young man to work as a camel driver before leaving to join the Turkish Army. He returned to Australia around 1912, but had difficulty finding work in the by-then declining camel trade. Instead, Gool Muhammad worked in the silver mines for a time until he was laid off, and then began operating an ice cream vending cart to earn a living.

Mullah Abdullah was the older of the two. Born around 1855, also in the North-West Frontier region, he was a literate Dari speaker who came to South Australia about 1890, probably working as a cameleer around Broken Hill from 1899. He probably also struggled to find further work as a cameleer in the years before the First World War, leading him to work as a halal butcher.

In the immediate aftermath of the events of 1 January 1915, journalists, likely ignorant of both the Broken Hill Ghantown and Islam itself, claimed that Abdullah was called “Mullah” as an indication of his status as a mullah, or Muslim priest. However, Australian Muslim scholar Dr. Abu Bakr Sirajuddin Cook doubts this. Firstly, he writes, “Islamic practice does not require formal qualifications for the halal slaughter of meat.” Moreover, both men were drug users – “they smoked together Indian hemp [i.e., cannabis], known to the natives by the name of gungha,” according to The Barrier Miner, allegedly sometimes mixed with laudanum. Not only is drug use forbidden in Islam, it would be utterly unacceptable for a religious leader.

Abdullah lived separately from his fellow Muslims in Williams Street. He had been fined several times for improper butchering, and he had struggled to work without membership in the Butchers’ Union. He found a sympathetic ear in Muhammad, who would vent his simmering anger at his loss of work. Both men had suffered racial discrimination from the townspeople, and both were increasingly bitter and nationalistic. And finally, with the Sultan’s call to war, they felt they’d found an outlet for their grievances.

The Picnic Train Attack

The Silverton Tramway train, made up of two brake vans and 40 ore cars with temporary benches, left Sulphide Street Station at around 10 o’clock on Friday morning. It made a single stop to collect extra passengers and then proceeded through the outskirts of town. Near the cattle yards, some of the passengers noticed Gool Muhammad’s white ice cream cart parked near a water main embankment for a nearby reservoir, sporting a Turkish flag and with two men crouching nearby.

Shots were fired. The passengers thought this was part of the festivities, and some even cheered. They only began to understand once they noticed the casualties. Sanitation inspector William Shaw pitched forward with a bullet wound in his back, saying “I’m shot.” Shaw’s daughter Lucy suffered a wound to her elbow. 17-year-old Alma Cowie died in her boyfriend’s arms with a wound to the head. Alfred Millard, the supervisor for the water pipe, was shot off his bicycle as he rode out to repair a leak. Four others were wounded.

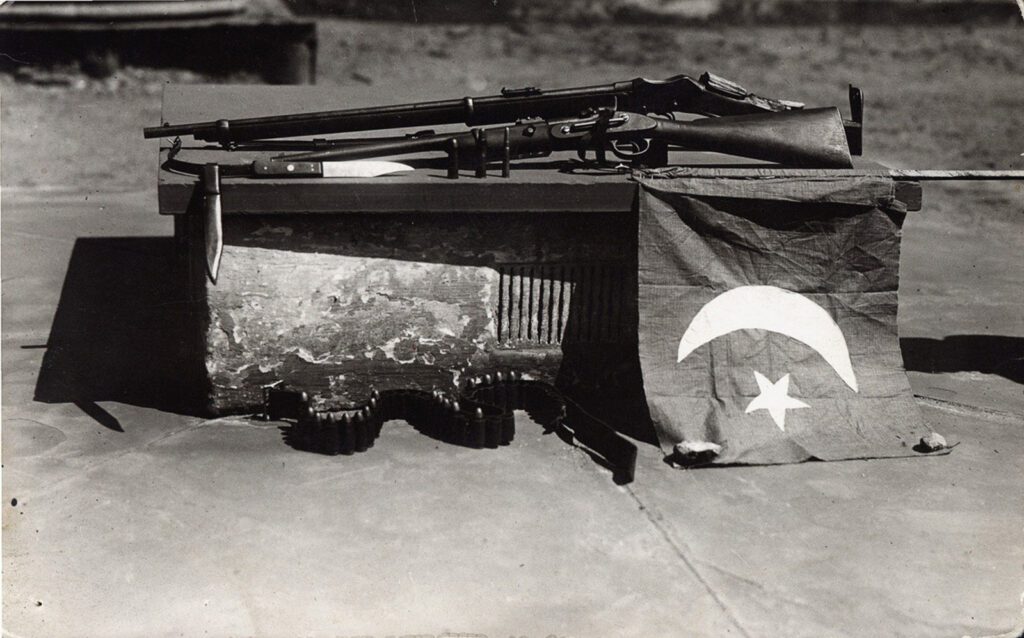

Gool Muhammad and Mullah Abdullah had traveled to the spot that morning, Muhammad carrying a Martini-Henry rifle and Abdullah with an aged Snider-Enfield rifle, with 80 antiquated cartridges bought from Frank Pincome’s shop in town. (Pincome had been only too glad to shift ten-year-old stock for a rifle which had been out of use by British forces for 30 years.) Abdullah had written a letter of intention in which he claimed to have attacked “for my faith, in obedience to the order of the Sultan and the order of the Koran.”

When the train, full of now-panicked passengers, stopped at a siding 850 yards away, the attackers resumed firing until the engine was started again and the train driven almost a mile on. Assistant guard William Elsegood ran to a nearby pumping station to raise the alarm, while Muhammad and Abdullah made their escape.

The Battle of Broken Hill

The response from the townspeople was rapid. Police contacted a Lieutenant Resch at the nearby army camp for assistance, and two cars loaded with armed men arrived at the scene of the attack at 10:50. On the way back to their camp, Abdullah and Muhammad shot 70-year-old tinsmith Thomas Campbell in the stomach.

Meanwhile, the police, now in just one car after the other had broken down, spotted the fleeing attackers north of the West Camel Camp. Abdullah and Muhammad ran onto Cable Hill, a quartz outcrop, turned, and fired on their pursuers. The police were reinforced by local militiamen and rifle club members. A nearby resident, 69-year-old labourer James Craig, ignored advice to come inside out of his yard, suffered a shot to the hip, and died the next day.

In the ensuing battle, “the general operations,” reported The Barrier Miner, “were under the direction of Inspector Miller and Lieutenant Resch. The attacking party spread out on the adjoining hills, and there was a hot fire poured into the enemy’s position, the Turks [sic] returning the fire with spirit but without effect, which is rather surprising, as the range was short, and the attacking parties in some cases exposed themselves rather rashly in their efforts to get a shot. There was a desperate determination to leave no work for the hangman, or to run the risk of the murderers of peaceful citizens being allowed to escape.”

At 1 o’clock, the pursuit party rushed Muhammad and Abdullah’s position. Abdullah, who in his letter had “asked God that I might die an easy death for my faith,” was found dead on the ground. Muhammad was barely alive, with one bullet wound “through the upper part of the chest on the right side; one had grazed the root of the neck on the left side; one had gone through the right forearm; the fingers of his left hand were lacerated, and there was a bullet wound in the left thigh.” He died soon afterwards from shock; a letter from Sultan Mehmed V was found in his waist-belt thanking him for his Turkish Army service. The pursuers suffered one casualty, Constable Robert Mills, who was wounded twice and survived.

Both bodies were buried in secret by an Aboriginal tracker beneath “the floor of a public building used for storing mine explosives.” The local Muslim population, infuriated at the pair’s attack on unarmed civilians, refused to allow them to be buried in hallowed ground.

Was Broken Hill Australia’s First Terrorist Tragedy?

The Battle of Broken Hill prompted frantic fury in the area and nationwide in the following weeks. On the evening of 1 January, a mob stormed the Broken Hill German Club and torched it. Fearing a similar attack on the North Camel Camp, a party of police and soldiers was dispatched to offer their protection. When the mob arrived, these men held them off long enough for the crowd’s fury to wane, and the camp was safe.

Nevertheless, the national attitude to Australians and residents of German and Turkish descent turned decidedly hostile in the aftermath. On Sunday, 3 January, Prime Minister Billy Hughes said “I see it is alleged to have been the act of Turks. If so it shows the necessity for rigid supervision of all enemy subjects.” On 5 January, all employees deemed enemy aliens were fired from Broken Hill’s mines, and several Germans, Austrians, and Turks were ejected from the town.

Misinformation ran rife. After the Sydney paper The Bulletin published a humour piece lampooning the Germans’ response as praising an overwhelming Turkish victory in Australia, numerous other papers picked up the story as genuine. Similarly, the Melbourne Herald and several other Australian papers circulated a story purportedly sourced from a “Mrs H. Philipson, of Lowe street, Marrickville, N.S.W.” In it, Mrs. Philipson (who exactly that was and how she had obtained the information was never explained) claimed that the official response in Berlin had it that “a force of Turks surprised and put to flight a superior force, which was being transported by rail. Forty of the enemy were killed and seventy wounded; the casualties among the Turks being only two killed.” This “victory” supposedly left “the way open for an attack on Candbris, the capital of Australia, and its most strongly fortified centre.”

Perhaps the most enduring error was in describing the attack. In the years after the September 11 2001 attacks in New York, and again after the 2014 Lindt Cafe siege in Sydney, media outlets and bloggers rediscovered the Picnic Train Attack and commonly branded it “Australia’s first terrorist attack.”

Scholars have pushed back against this label. The Broken Hill attack, say experts like Dr. Cook and Christine Adams, historian and curator of the Sulphide Street Railway and Historical Museum, was not an attempt to inflict terror or destabilise Australian society. Instead, it should be understood as the expression of deeply felt grievances on the part of Gool Muhammad and Mullah Abdullah as Muslims and Asian men in a rigidly racialised society.

Muhammad and Abdullah were among what historian Christine Stevens called “the untouchables in a white Australia.” Adams also notes that Abdullah was frequently bullied by local boys, who pelted him with stones and shouted racial abuse at him. And even when they still had work as cameleers, both men were subject to racial and professional discrimination from unionised Australian teamsters, who disliked the cameleers’ foreignness and their competitiveness providing a more efficient service at a lower cost.

It’s beyond question that Mullah Abdullah and Gool Badsha Muhammad committed a heinous crime. Bitter, frustrated, isolated, and far from home, they lashed out at innocents, killing and wounding in response to their treatment. Nevertheless, this was not an ideological attack, but a tragic example of what can happen when people pushed to the fringes of society react with anger and violence.

Articles you may also like

Vietnam: The Advisory Years to 1965 – Audiobook

VIETNAM: THE ADVISORY YEARS TO 1965 – AUDIOBOOK By Robert Futrell (1917 – 1999) This book explains the policy of the United States and France toward Vietnam beginning after World War II until the beginning of America’s entry into the Vietnam War in 1965. Please leave this field emptyTell me about New Quizzes and Articles Get […]

History’s Greatest Nicknames

Reading time: 7 minutes

A browse through any military history book will no doubt bring up titles of famous officers, often bearing unusual, surprising, or sometimes downright hilarious nicknames. In many cases, it’s clear where the sobriquet originated, while other examples hold a less-obvious significance.