Why January 6 Was Not Like a Banana Republic

Reading time: 5 minutes

After the January 6 insurrection, many observers, including former US presidents, current legislators, pundits, journalists, and editorial writers invoked the mob violence and bloody mayhem as the usual political culture of so-called “banana republics.” Although it is an easy comparison to make, Latin Americanists found this galling, because the term refers to a specific economic and political trope created by and in service to US interests. Using the phrase banana republic to describe any attempted coup or insurrection draws on a century of stereotypes about Latin America created by the US to serve US interests. As a description of the events of January 6, the comparison lacked both subtlety and accuracy.

By Dario A. Euraque

When it is invoked to describe nations, banana republic conjures up a range of clichés and caricatured images of US–Central American and Caribbean diplomatic relations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Coined by O. Henry in a 1904 story collection, Of Cabbages and Kings, banana republics referred to countries led by dictators, oligarchs, and “strongmen,” who ruled over Indigenous and/or mixed-race peasants, and managed economies dependent on agricultural exports, stereotypically coffee or bananas. The labor force in these economic ventures in the Caribbean were usually descendants of enslaved people participating in anti-imperial struggles against Spanish colonialism.

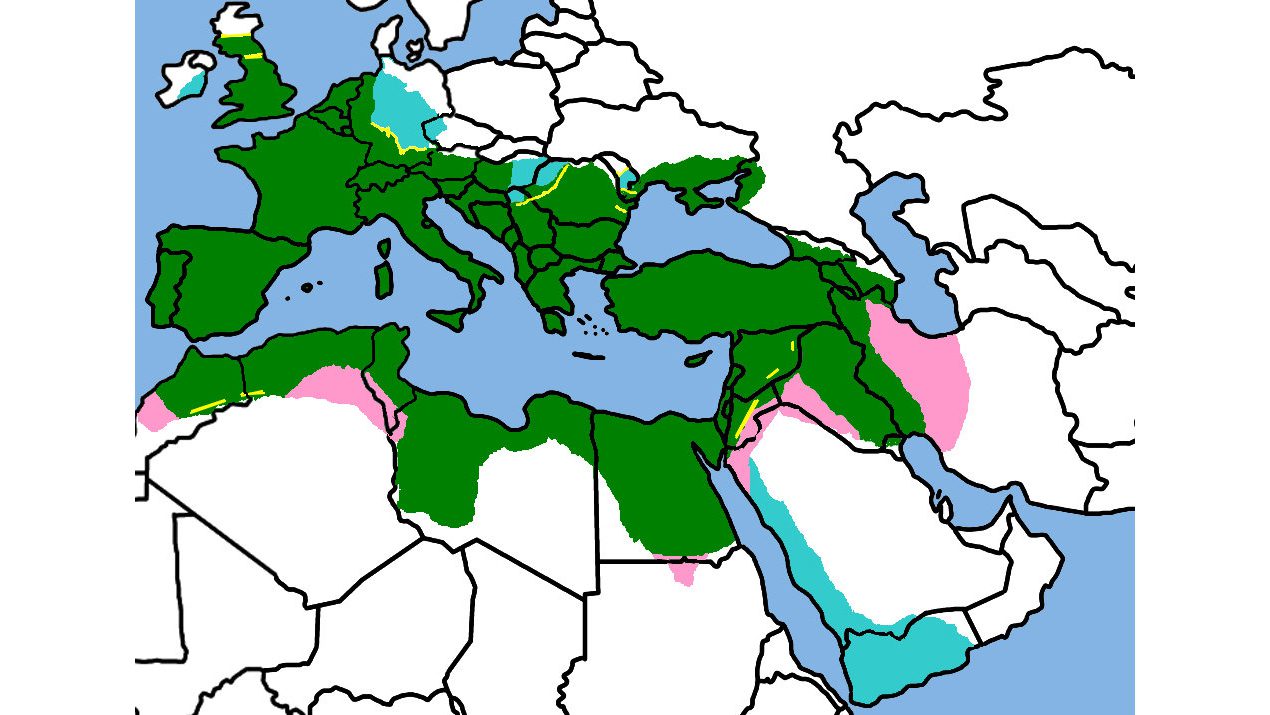

US citizens, diplomats, and military men who ventured into Latin America in the late 19th century brought with them visions of their country’s place in the world grounded in white supremacy and colonialism. Drawn to the region’s rich agricultural products, mining, and natural resources, Americans viewed the region as a racially backward place ripe for exploitation. From the outset, so-called banana republics were linked to racial and cultural legacies left by colonialism in Honduras, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Panama. Honduras, the first nation to be branded a banana republic in 1904, denounced American involvement in the region’s economics and government as early as the 1850s.

By 1929, Honduras was the main exporter of bananas in the world. Enterprises owned by two US corporations, the United Fruit Company and the Standard Fruit Company, financed wars among Honduran elites to secure concessions to build railroads, develop banana plantation infrastructure, and obtain tax-free imports. O. Henry’s writings on Honduras served as a primer on the region for Americans arriving after these wars. As John Soluri has shown in Banana Cultures, marketing campaigns promoting the general consumption of bananas among US citizens at this time assumed O. Henry’s views about the countries where this commodity originated.

Henry’s writings did far more than create a US market for an agricultural commodity; they shaped an expansionist US policy in the region. For many in this generation of US agents in Latin America, the end goal was to annex these economically productive but politically unstable so-called banana republics, including Cuba and Honduras. Long before he headed the FBI between 1924 and 1972, J. Edgar Hoover favored the annexation of Cuba in a primary school debate. In fact, before the CIA was created at the end of the 1940s, Hoover placed FBI agents in much of the Caribbean and Central America to support the dictators who ruled these nations.

Beginning in the 1930s, the United Fruit Company dominated the banana republics. United Fruit Company was headed by Sam “the Banana Man” Zemurray, who enjoyed close relations with the US State Department and the CIA. In 1954, Zemurray used the CIA to support a military coup against the president of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz, who had challenged Zemurray’s monopolies. During this period, US diplomats appeared either as active agents of US corporations or as negligent facilitators of a neocolonial American empire. The US military served these corporate and national interests by providing “protection” to the economic interests of white US elites. Until 1959, US diplomatic relations with these nations were framed by the imposition of imperialistic political and economic policies and hegemony, from the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, Dollar Diplomacy, and the Good Neighbor Policy in the 1930s and 1940s.

After 1950, Good Neighborliness succumbed to Cold War posturing between the US and the Soviet Union and their allies. Between the 1960s and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, US diplomacy often drew on the caricature of banana republics. The origins and course of the Cuban Revolution, for example, were often caricatured as another example of a civil war conflict mired in banana republic politics and lacking democratic goals and issues of equity. The US invasion of Panama in 1989, authorized by President George H. W. Bush, a former CIA chief, apprehended dictator Manuel Antonio Noriega. In framing the invasion around Noriega’s indictment for cocaine trafficking and his status as a paid informant of the CIA, the government and media reinforced the banana republic stereotype that had shaped US perceptions of the region for 80 years.

Stereotypes and parodies of the banana republic were common in travelogues, films, newsreels, military documentaries, school textbooks, and mass-produced school slideshows from the 1950s through the 1980s. These include Jacques Tourneur’s Appointment in Honduras (1953) and Woody Allen’s Bananas (1969). The stereotype even shows up in films that purport to critique US intervention in Nicaragua during the Reagan administration, such as Alex Cox’s Walker (1987).

Parody and critique of this kind, to say nothing of real historical context, were ignored in the press coverage of the January 6 insurrection. Invoking the banana republic trope, created originally to mask a diplomatic chauvinism committed to furthering narrow economic interests and empire building in Latin America, while ignoring its historical origins, did a disservice to the complexity and danger of the assault on democracy by a minority faction.

This article was originally published in Perspectives on History.

Articles you may also be interested in

Reckoning with slavery: What a revolt’s archives tell us about who owns the past

Reading time: 6 minutes

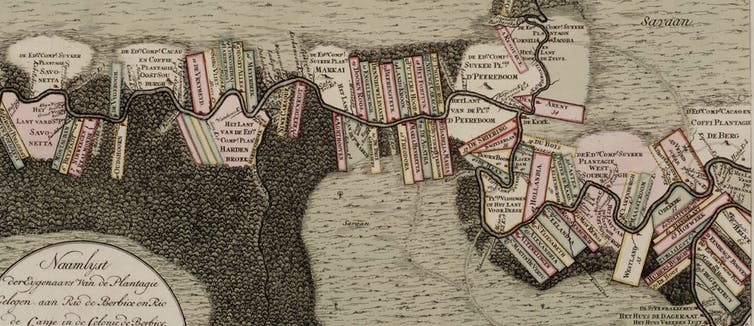

During the revolt, former slaves organized a government and controlled most of the colony for almost a year. The Dutch either fled altogether or holed up on a well-fortified sugar plantation near the coast. A regiment of European soldiers sent from neighboring Suriname mutinied and joined the rebels they had come to defeat. But obligated by treaties, indigenous peoples such as Carib and Arawak fought on the side of the Dutch. The revolt ended when the rebels, out of food and arms, were overpowered by enemies who had received an infusion of men and supplies from the Dutch Republic.

The text of this article is republished from Perspectives on History under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.