Reading time: 6 minutes

Finding shipwrecks isn’t easy – it’s a combination of survivor reports, excellent archival research, a highly skilled team, top equipment and some good old-fashioned luck.

And that’s just what happened with the recent discovery of SS Iron Crown, lost off the coast of Victoria in Bass Strait during the second world war.

By Emily Jateff, James Cook University and Maddy McAllister, Flinders University.

Based on archival research by Heritage Victoria and the Maritime Archaeological Association of Victoria, we scoped an area for investigation of approximately 3 by 5 nautical miles, at a location 44 nautical miles SSW of Gabo Island.

Hunting by sound

We used the CSIRO research vessel Investigator to look for the sunken vessel. The Investigator deploys multibeam echosounder technology on a gondola 1.2 metres below the hull.

Multibeam echosounders send acoustic signal beams down and out from the vessel and measure both the signal strength and time of return on a receiver array.

The receiver transmits the data to the operations room for real-time processing. These data provide topographic information and register features within the water column and on the seabed.

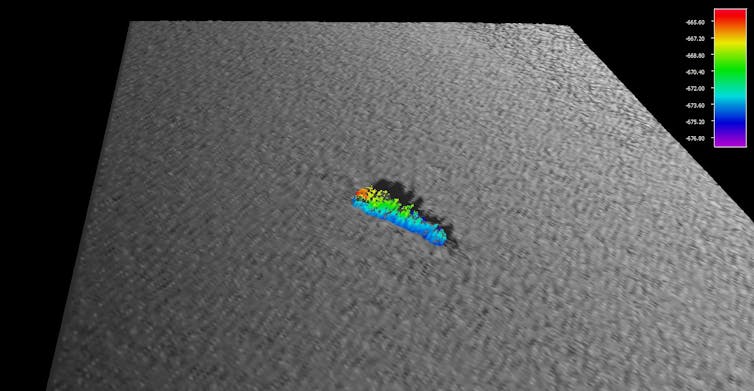

At 8pm on April 16, we arrived on site and within a couple of hours noted a feature in the multibeam data that looked suspiciously like a shipwreck. It measured 100m in length with an approximate beam of 16-22m and profile of 8m sitting at a water depth of 650m.

Given that we were close to maxing out what the multibeam could do, it provided an excellent opportunity to put the drop camera in the water and get “eyes on”.

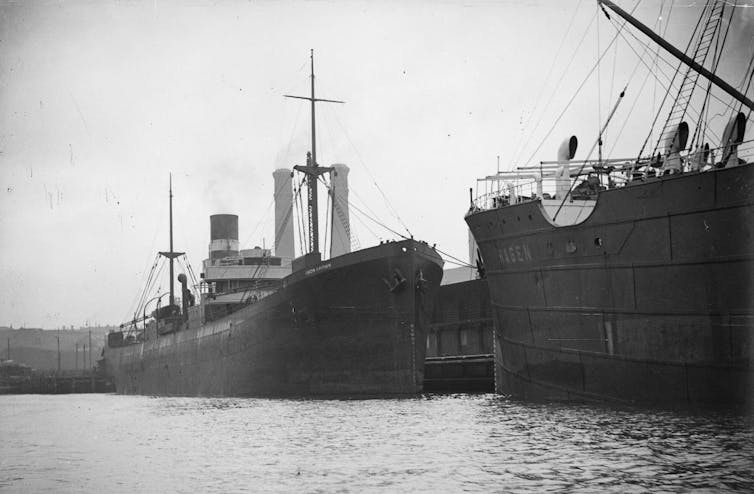

The camera collected footage of the stern, midship and bow sections of the wreck. These were compared to archival photos. Given the location, dimension and noted features, we identified it as SS Iron Crown.

The merchant steamer

SS Iron Crown was an Australian merchant vessel built at the government dockyard at Williamstown, Victoria, in 1922.

On June 4 1942, the steel screw steamer of the merchant vavy was transporting manganese ore and iron ore from Whyalla to Newcastle when it was torpedoed by the Japanese Imperial Type B (巡潜乙型) submarine I-27.

Survivor accounts state that the torpedo struck the vessel on the port side, aft of the bridge. It sank within minutes. Thirty-eight of the 43 crew went down with the ship.

This vessel is one of four WWII losses in Victorian waters (the others were HMAS Goorangai lost in a collision, SS Cambridge and MV City of Rayville lost to mines) and the only vessel torpedoed.

After the discovery

Now we’ve finally located the wreck – seven decades after it was sunk – it is what happens next that is truly interesting.

It’s not just the opportunity to finally do an in-depth review of the collected footage stored on an external hard drive and shoved in my backpack, but to take the important step of ensuring how the story is told going forward.

When a shipwreck is located, the finder must report it within seven days to the Commonwealth’s Historic Shipwreck Program or to the recognised delegate in each state/territory with location information and as much other relevant data as possible.

Shipwrecks aren’t just found by professionals, but are often located by knowledgeable divers, surveyors, the military, transport ships and beachcombers. It’s no big surprise that many shipwrecks are well-known community fishing spots.

While it is possible to access the site using remotely operated vehicles or submersibles, we hope the data retrieved from this voyage will be enough.

It was only 77 years ago that the SS Iron Crown went down. This means it still has a presence in the memories of the communities and families that were touched by the event and its aftermath.

No war grave, but protected

Even though those who died were merchant navy, the site isn’t officially recognised yet as a war grave. But thanks to both state and Commonwealth legislation, the SS Iron Crown was protected before it was even located.

All shipwrecks over 75 years of age are protected under the Commonwealth Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976. It is an offence to damage or remove anything from the site.

This protection is enhanced by its location in deeper water and, one hopes, by the circumstances of its loss.

Sitting on the sea floor in Bass Strait, SS Iron Crown is well below the reach of even technical divers. So the site is unlikely to be illegally salvaged for artefacts and treasures.

Yet this also means that maritime archaeologists have limited access to the site and the data that can be learnt from an untouched, well-preserved shipwreck.

Virtual wreck sites

But, like the increasing capabilities for locating such sites, maritime archaeologists now have access to digital mapping, 3D modelling technologies and high-resolution imagery as was used for the British Merchant Navy shipwreck of the SS Thistlegorm.

These can even allow us to record shipwreck sites (at whatever the depth) and present them to the public in a vibrant and engaging medium.

Better than a thousand words could ever describe, these realistic models allow us to convey the excitement, wonder and awe that we have all felt at a shipwreck. Digital 3D models enable those who cannot dive, travel or ever dream of visiting shipwrecks to do so through their laptops, mobiles and other digital devices.

Without these capabilities to record, visualise and manage these deepwater sites, they will literally fade back into the depths of the ocean, leaving only the archaeologists and a few shipwreck enthusiasts to investigate and appreciate them.

So that’s the next step, a bigger challenge than finding a site, to record a deepwater shipwreck and enable the public to experience a well-preserved shipwreck.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcast about the discovery of SS Iron Crown

Articles you may also like:

Damien Parer, Australia’s Iconic WW2 Photographer – Podcast

Parer was selected as an official war photographer for the Department of Information. He would go on to record many of the iconic images of Australian troops in that war.

Australian VC’s in the Mediterranean, WWII – Video

There were six Australian VC recipients during the Mediterranean and North African Campaigns of the second world war. From the heroics of Lt. Roden Cutler in Damour, Corporal Edmondson of the Desert Rats defending Tobruk in 1941 to Sgt. Kibby with his tommy-gun in El Alamein. Learn more about Australian gallantry in the Deserts of North Africa.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.