Reading time: 5 minutes

It’s only February and already 2022 is shaping up badly. A huge volcanic eruption off the coast of Tonga, the prospect of war with Russia, the ongoing pandemic (and its economic disruptions). And that’s even before we touch on Chinese sabre-rattling over Taiwan or Sex and the City’s disastrous reboot.

Welcome to the New Year: as ghastly as the old one.

By Miles Pattenden, Australian Catholic University

A history of bad times

I write not to make light of our world’s very real problems, but rather to put them into some perspective. 2020, 2021 and perhaps now 2022, have all been bad.

But they have not been worse years than, say, 1347, when the Black Death began its long march across Eurasia. Or 1816, the “year without a summer”. Or 1914, when the assassination of an obscure Habsburg archduke precipitated not one but two global conflicts – one of which brought about millions of deaths in the world’s most horrific genocide.

There have been plenty of other bad years, and decades, too. In the 1330s, famine set in and ravished Yuan China. In the 1590s a similar famine devastated Europe, and the 1490s saw smallpox and influenza begin to work their way through the indigenous populations of the Americas (reciprocally, syphilis did the same amongst inhabitants of the Old World).

Life has often been “nasty, brutish, and short”, as the political philosopher and cynic Thomas Hobbes observed in his Leviathan in 1651. And yet historians, even now, sometimes point to one particular year as worse than the others.

Yes, there may have been a time within historical memory when it really was the worst hour to be alive.

536: the worst year in history?

536 is the current consensus candidate for worst year in human history. A volcanic eruption, or possibly more than one, somewhere in the northern hemisphere would seem to have been the trigger.

Wherever it was, the eruption precipitated a decade-long “volcanic winter”, in which China suffered summer snows and average temperatures in Europe dropped by 2.5℃. Crops failed. People starved. Then they took up arms against each other.

In 541 bubonic plague arrived in Egypt and went on to kill around a third of the population of the Byzantine empire.

Even in distant Peru, droughts afflicted the hitherto flourishing Moche culture.

Increased ocean ice cover (a feedback effect of volcanic winter) and a deep solar minimum (the regular period featuring the least solar activity in the Sun’s 11-year solar cycle) in the 600s ensured that global cooling continued for more than a century.

Many of the societies living in 530 simply could not survive the upheavals of the decades that followed.

The new ‘science’ of climate history

Historians now take a particular interest in subjects such as this because we can collaborate with scientists to reconstruct the past in new and surprising ways.

Only a fraction of what we know, or think we know, about what happened during such murky moments now comes from traditional written sources. We have a few for 536: the Byzantine historian Procopius wrote that year that “a most dread portent has taken place”, and the Roman senator Cassiodorus noted in 538

[…] the sun seems to have lost its wonted light and appears a bluish colour. We marvel to see no shadows of our bodies at noon and to feel the mighty vigour of its heat wasted into feebleness.

Yet the real strides in historical understanding of this “worst ever year” are emerging through application of such advanced techniques as dendroclimatology and analysis of ice cores.

Dendroclimatologist Ulf Büntgen detected evidence of a cluster of volcanic eruptions, in 536, 540 and 547, in patterns of tree-ring growth. Likewise, “ultraprecise” analysis of ice from a Swiss glacier undertaken by archaeologist Michael McCormick and glaciologist Paul Mayewski has been key to understanding just how severe the climate change of 536 was.

Such analyses are now seen as important, even essential, resources in the historian’s methodological toolkit, especially for discussing periods without an abundance of surviving records.

Some historians – including Kyle Harper, Jared Diamond and Geoffrey Parker – use developments in this growing field to construct whole revisionist narratives about the rise and fall of particular societies. For them, conditions on our planet are far more significant in driving our history forward than we ever realised.

Coping with adversity

But what was it like living through a climate-changing event such as that which began in 536? It’s a question historians continue to ponder as we sift through our sources.

Most of those alive in 536 probably didn’t know they had it so bad. As historians, we are prone to over-rely on anecdotal doom-laden snippets like the quotations from Procopius and Cassiodorus.

Yet, like the proverbial frog in boiling water, the average person back then may only have realised slowly just how grim conditions in their world were getting. The worst moment would not in fact have been in 536 but some time after – when the full effects of plagues and droughts, chills and famines had truly set in.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about the year 536:

Articles you may also like:

General History Quiz 46

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. Have an idea for a question? Submit it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! If you would like an invite to future history quizzes please enter your details below. Subscribe * indicates required Email Address * First Name Last Name […]

3 Squadron RAAF – Podcast

As the Allied armies fought across North Africa, first against the Italians and then the Vichy French and Rommel’s Afrika Korps, one squadron of the RAAF was there from the beginning. No. 3 Squadron was the first RAAF squadron to leave Australia and played an important part in many of the important battles from 1940 to 1943 across North Africa, Tunisia and Sicily.

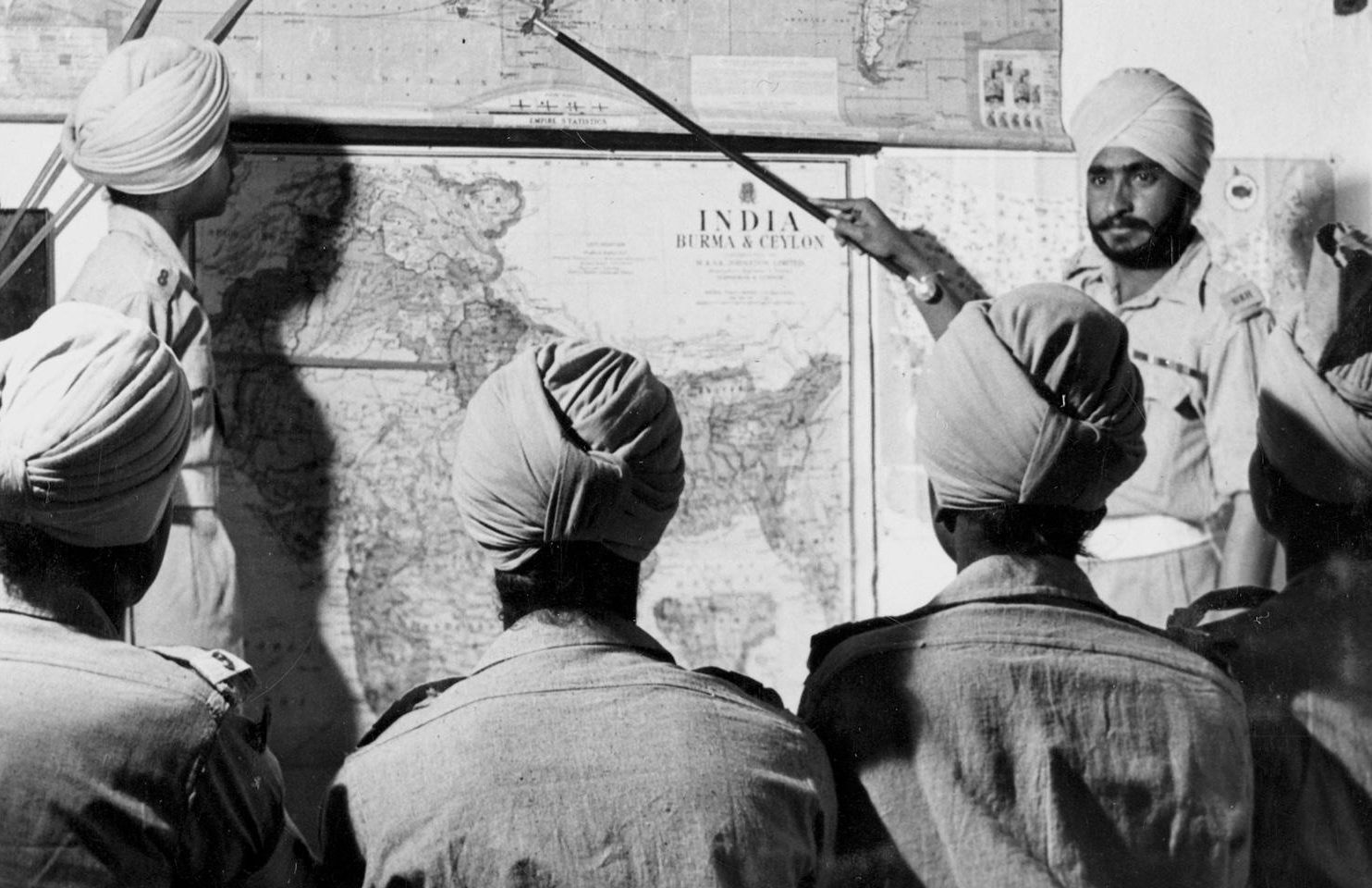

Five myths about the partition of British India – and what really happened

Reading time: 6 minutes

This August marks 75 years since the partition of the Indian subcontinent. British withdrawal from the region prompted the creation of two new states, India and Pakistan.

The process of transferring power grossly simplified diverse societies to make it seem like dividing social groups and drawing new borders was logical and even possible. This decision unleashed one of the biggest human migrations of the 20th century when more than ten million people fled across borders seeking safe refuge.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.