Reading time: 12 minutes

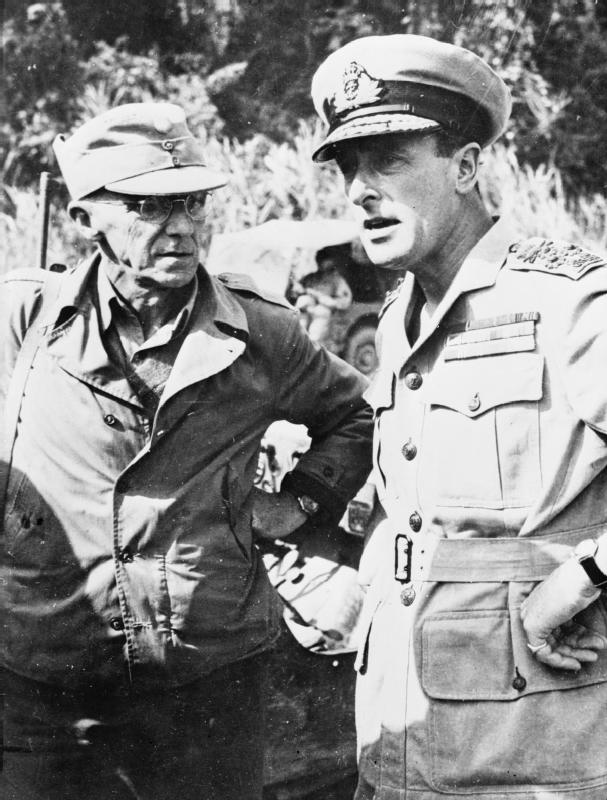

As famed as American commanders like Dwight Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur are today, one of the most important is the relatively little-known Joseph Stilwell.

Dubbed “Vinegar Joe” for his acidic tongue and temperament, Stilwell was one of the finest officers of the United States Army when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor.

By Morgan WR Dunn

Most importantly, he was one of its leading experts on a country that was to play a pivotal role in the history not just of the war, but of the 20th century: China.

Stilwell seemed to vocally hate just about everybody he shouldn’t have, and wasn’t afraid to insult and berate anyone he thought stood in his way. But, practically alone on the far side of the Pacific, “Vinegar Joe” also marshaled scant resources and men against a backdrop of distrust, incompetence, and a hellish war of conquest to help the Allies carry the day.

A NEW JOB FOR JOE

Joseph Warren Stilwell became a professional soldier at a time when the job was very much out of favor in the United States. Entering a peacetime army of only 50,000 in 1904, Stilwell filled his early career with tours of duty in World War I, the Philippines, and China, where he mastered the language and first saw the ancient grandeur of the culture, as well as the chaos and corruption which had reigned since the collapse of the last imperial dynasty.

By the time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Stilwell’s mastery of operational planning was recognised by his appointment to devise the Allied invasion of North Africa. But on 14th January, 1942, he was invited for “a fatherly talk” with Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson.

Stimson wanted to talk about what appeared to be a dead-end job: military advisor to Chiang Kai-shek, the ruler of Nationalist China, which had been locked in a harrowing war with Japan since as early as 1931. Although Stilwell thought the Chinese might remember him as “a small-fry colonel that they kicked around,” he nevertheless told Stimson he would go where he was sent.

“More and more,” Stimson told him, “the finger of destiny is pointing at you.” On 23rd January, “the blow fell”: Stilwell would spend the war in China.

FIGHTING FOR AND WITH CHIANG

In 1942, Chiang’s National Revolutionary Army served as the nominal national military alongside several warlord factions which had survived the turmoil of the 1920s and 1930s. Combined with Chiang’s obsession with destroying the Chinese Red Army, this dangerously disunified army was ill-equipped to resist the vast and aggressive forces of the Empire of Japan.

Chiang and his ambassador in the United States, T.V. Soong, insisted that poor-quality equipment was the problem. Stilwell disagreed; he “attributed their defeats to ignoring the basic principles of strategy and tactics, poor intelligence, bad staff work, and bad maintenance of weapons, vehicles and equipment.”

To counteract these problems, Stilwell demanded overall command of all Chinese forces, to which Chiang agreed but would never make good. However, Stilwell would control the flow of vital Lend-Lease materials to the NRA, effectively making him China’s quartermaster and armorer.

Stilwell despised the corrupt officers and politicians of China’s Nationalist government, but he also firmly believed that Chinese soldiers had just as much potential as American or European ones. “The Chinese soldier,” he declared, “is one of the best in the world. If he has the equipment and supplies, no one can lick him.”

All he had to do now was get that equipment into Chinese hands. The circuitous way ahead began in the British colony of Burma, where the Japanese were about to win a crushing victory.

TURNING THE TABLES IN BURMA

As long as Japan controlled the seas and skies in eastern China, the shortest and safest route for Lend-Lease supplies to enter the country was through Burma. By March 1942, just weeks after Stilwell arrived in theater, Japanese forces succeeded in cutting this route, making his first task to reopen it. But the routed troops available to him were too exhausted, disorganised, underequipped, and ill-trained.

By May, Stilwell, then 59 years old, chose to retreat on foot, leading his staff to safety in India. Once he’d arrived, he told reporters “I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”

Discussing the failure with Stimson and General George Marshall, Stilwell outlined his plan to make good. With a reformed and retrained Chinese army, he would open a new route, the Burma Road, to carry supplies over the Himalayas, a daunting obstacle known to Allied personnel as “the Hump.”

His plans clashed with those of General Claire Lee Chennault, commander of U.S. air forces in China, who enjoyed a friendlier relationship with Chiang and argued in favor of airlifts to supply the Chinese. Stilwell also irritated British leaders, whose priority was India, by disagreeing with their strategy and, frequently, by accusing them and their men of cowardice and incompetence.

British and Chinese leaders were unwilling to commit troops for the recapture of Burma. Physically weakened after the retreat and with no real power, Stilwell arrived in Chongqing, China’s wartime capital, on 3rd June. For the next two years, he would fight the war in offices and boardrooms, and his opponent, as he saw it, was not Japan, but Chiang himself.

STILWELL’S GRAND PLANS

Joseph Stilwell was the archetypal simple American military man. Unlike his Chinese and British counterparts, whom he saw as “all pose and bumptiousness,” he dispensed with medals and insignia, wore his old World War I campaign hat, and carried a Model 1903 Springfield rifle instead of a sidearm.

His disdain for ceremony and his concern for his men led them to nickname him “Uncle Joe.” To most others, however, the old “Vinegar Joe” was closer to the truth. And for Chiang Kai-shek, Stilwell had a derisive nickname of his own: “Peanut,” a term coined by a member of Stilwell’s staff who said the Chinese leader was like “a peanut perched on top of a dung heap.”

In Stilwell’s view, Chiang was more interested in preserving his power and Lend-Lease supplies to fight the Communists than the Japanese, and was willing to overlook massive corruption in his ranks. In Chiang’s, China had already borne the brunt of the fighting for a decade, and Stilwell’s attempts to overhaul the Chinese army threatened to undermine his delicate hold on power.

Stilwell wanted to reforge China’s army into modern, highly-trained divisions built along American lines capable of destroying the Japanese in the field. But any attempt to divert men from his supporters’ armies would weaken Chiang’s position, and while he often agreed to Stilwell’s plans in person, he obstructed them in practice.

“Chiang’s resistance to Stilwell’s proposals,” wrote historian Barbara Tuchman in her seminal biography of the general, “was never fixed or solid but changeable and vacillating in proportion to what he thought Stilwell could obtain for him from America.”

His goal was to collect as much weaponry and material as possible to strengthen his forces while Chennault’s air units, which actually received the bulk of Lend-Lease supplies, would hold off the Japanese.

Eventually, thanks to persuasion from Soong, Chiang agreed to supply Stilwell with 50,000 men to be transformed into an Americanised corps in India in exchange for guarantees of monthly deliveries of 5,000 tons of supplies via the Hump and 500 combat planes. It was nowhere close to Stilwell’s vision, but it would give him what he needed to achieve his obsession: a reversal in Burma.

TOO MUCH VINEGAR

Stilwell displayed an astonishing ability to make do with very little, often at the expense of the men under his command. At his disposal was just one American formation, the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), or Merrill’s Marauders, an early special forces unit.

Using the Marauders as regular infantry led to severe casualties: Stilwell would send sick men back to the front and dismiss their concerns about the hardships and horrors of jungle warfare. One Marauder, recalling a moment when he had Stilwell “in his sights,” said “I coulda’ squeezed one off and no one woulda’ known it wasn’t a Jap who got that son of a bitch.”

Stilwell was equally unpopular with British forces. When he gave all the credit for the Allied capture of the Burmese town of Mogaung to his Chinese troops, British commander Michael Calvert wired to Stilwell’s headquarters, “Understand Chinese have taken Mogaung. We have taken umbrage.” Stillwell’s son Joseph Jr., an intelligence officer, unhelpfully replied that “umbrage must be a very small village because he could not find it on the map.”

But Mogaung, along with the recapture of the strategically important town of Myitkyina, marked the turning of the tide. The victories allowed the Allies to reopen the Burma Road, re-energising Lend-Lease deliveries and leading Chiang to pay Stilwell a rare compliment by renaming the route the Stilwell Road. As Japanese forces weakened, China’s armies were reinvigorated and began to draw closer to victory.

THE FINAL INSULT

In desperation, Japanese commanders threw everything they had at one final terrifying attempt to crush China in Operation Ichi-Go. Over the course of eight grueling months, 500,000 Japanese troops succeeded in defeating Chinese forces numbering over a million. Although the victory couldn’t stop the eventual Japanese defeat, it was an enormous embarrassment for Chiang, particularly as an ascendant Mao Zedong’s army was beginning to collect victories.

At last, Stilwell thought, his chance had come to seize command in China. He appealed directly to President Franklin Roosevelt, who in turn sent an ultimatum via Stilwell: place the general “in unrestricted command of all your forces,” or the Lend-Lease tap would be shut off.

Roosevelt’s envoy Patrick J. Hurley warned Stilwell to wait to deliver the message, but Vinegar Joe wouldn’t hear of it. He finally had the chance to win his ongoing feud with the Chinese Generalissimo in the most satisfyingly insulting fashion possible.

After delivering the letter, he even wrote a celebratory poem in his diary, which began:

I’ve waited long for vengeance,

At last I’ve had my chance.

I’ve looked the Peanut in the eye

And kicked him in the pants.

VICTORY AND DEFEAT

Stilwell’s intended insult hit too close to the bone. The United States couldn’t afford to lose China as an ally, and Chiang knew it. Calling the message “the greatest humiliation I have been subjected to in my life,” he responded by demanding Stilwell’s recall. At last, on 19th October 1944, Stilwell wrote in his diary “THE AX FALLS.” He was being replaced.

Much of the Lend-Lease material which Stilwell had fought so hard to get to China, and which Chiang had been so reluctant to expend, would prove immensely useful – to the Communists, who would capture large amounts of weaponry, clothing, vehicles, ammunition, medicine, and other critical supplies in the Chinese Civil War, which resumed with a vengeance almost immediately after Japan’s defeat.

Chiang’s regime would collapse just a few years later, but Stilwell could take no satisfaction from it. He died while being treated for stomach cancer on 12th October 1946, almost exactly two years after he was ousted from China, a country he loved even as he hated its leaders.

Joseph Stilwell was in many ways the least agreeable of America’s top generals in the Second World War. Irritable, demanding, and confrontational, he lacked the diplomatic skill required for his sensitive assignment.

Nevertheless, his single-minded drive to achieve victory in Asia kept a beleaguered China in the fighting for years longer than it might have otherwise, and his uncommon respect for the much-derided Chinese soldier ensured that at least a few would achieve their potential when their country needed them most.

While his memory was obscured by Chiang’s defeat, Stilwell deserves to be remembered as a valiant soldier for the Allies who faced almost impossible odds and emerged as a critical figure in victory.

Podcasts about Joseph Stilwell

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 48

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. Have an idea for a question? Submit it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! Sign up to our Newsletter to get your weekly fill of History News, Articles and Quizzes Please leave this field emptyTell me about New Quizzes and […]

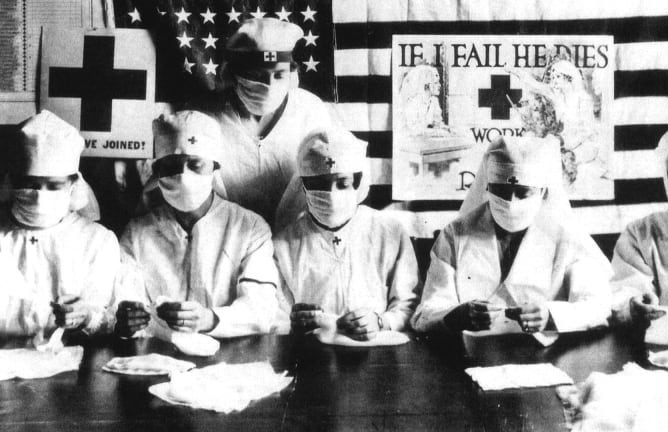

“The Flu”: A Brief History of Influenza in U. S. America, Europe, Hawaii

“THE FLU”: A BRIEF HISTORY OF INFLUENZA IN U. S. AMERICA, EUROPE, HAWAII By A. Mouritz (1861 – 1943) PREFACE This Booklet has been written and compiled for the use of any student or layman who seeks concise and clear information on the history of Influenza. Brief and salient facts are set forth relating to “Flu” […]

Warfare spurred on the welfare state in the 20th century – but it probably won’t in future

The link between warfare and welfare is counter-intuitive. One is about violence and destruction, the other about altruism, support and care. Even the term “welfare state” – at least in the English-speaking world – was popularised as a progressive and democratic alternative to the Nazi “warfare state” during World War II. And yet, as new research shows, […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.