Reading time: 5 minutes

The decision that Germany and the US will allow the export of M1 Abrams and Leopard 2 tanks to Ukraine, alongside the British Challenger 2 tanks promised in mid January is the culmination of Nato’s policy to assist Ukraine and an important symbolic step in the west’s response to Putin’s aggression.

By David Grummitt, The Open University

The export of German and US tanks to Ukraine is not without risk, both real and symbolic. In purely military terms, well-trained, well-led and motivated Ukrainian tank crews operating the Leopard 2 or M1 Abrams will be better protected, have better firepower and be more manoeuvrable than their Russian counterparts. Provided the Ukrainians can cope with the fact that they will need different ammunition, spare parts and possibly fuel they can make a difference, significantly enhancing Ukraine’s capability to defend its territory.

If these conditions are met and if the west makes available the 300 tanks that the Ukrainian leadership demands, they can be a gamechanger. Tanks can deliver rapid gains of territory to the Ukrainians in a summer offensive.

Just as important, however, is the need to continue to supply long-range artillery to Ukraine to degrade Russia’s logistical capabilities and destroy troop concentrations.

Replaying old stories

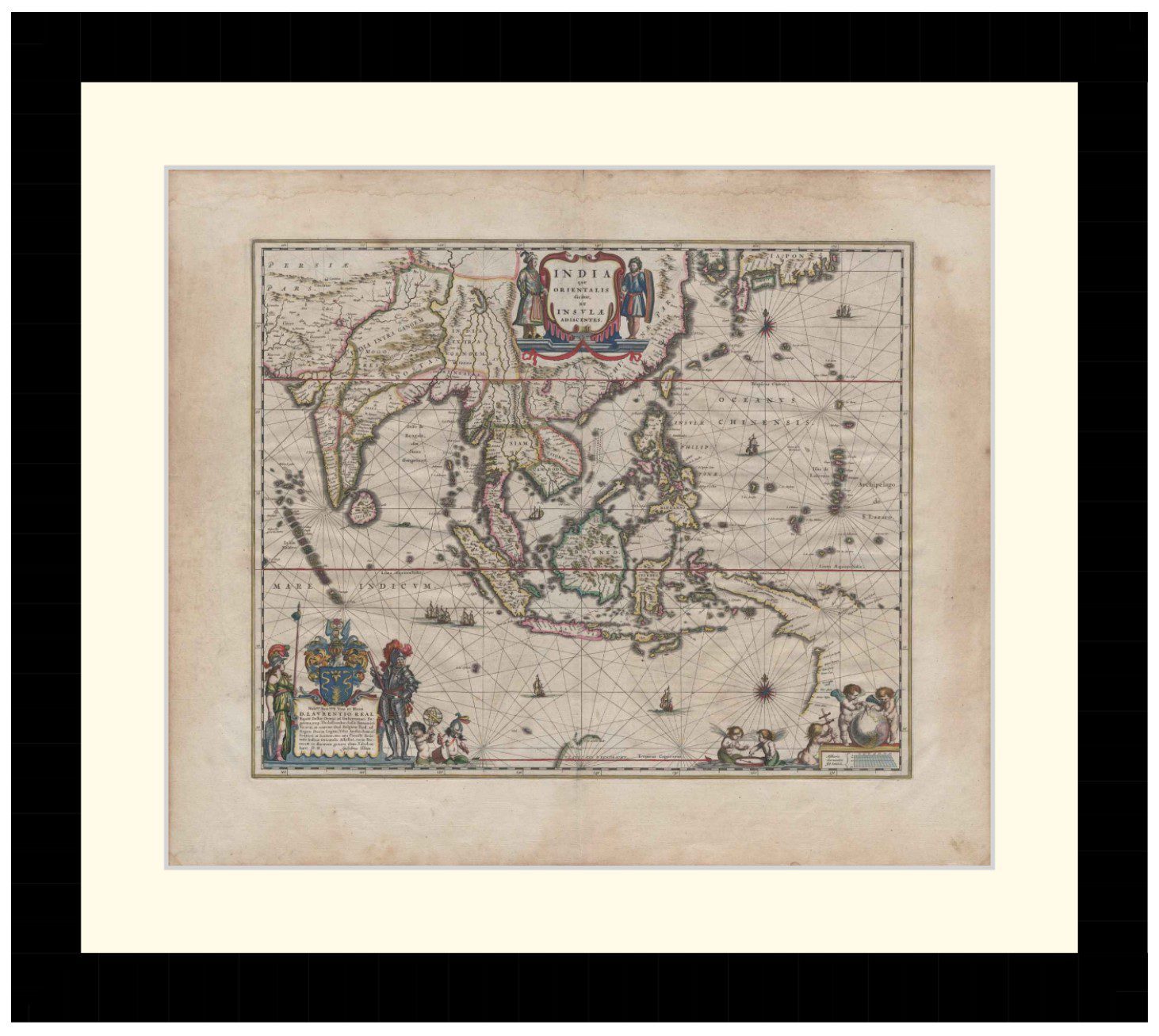

Symbolically, the presence of US and German-made tanks in Ukraine is more problematic. Nato’s cold war doctrine was largely based on the experience of German tanks in the second world war – especially during the Wehrmacht’s desperate retreat across Ukraine in 1943-44 when small groups of German tanks successfully counterattacked, delaying the Soviet Red Army’s advance.

The presence of Abrams and Leopard 2s in Ukraine promises to recreate the never-fought battles of the cold war with tanks and tactics designed for the clash of Nato and the Warsaw Pact armies across the German plains in the 1980s.

In the 1970s Nato and the Soviet Union faced each other across the border between East and West Germany. Leaders in both blocs were aware of a growing discrepancy in conventional forces, a crucial component of which was the “tank gap”. By the end of the decade the Soviets had 10,000 more tanks in Europe than Nato.

The newest Soviet tanks – the T-64 and the T-72 – were superior to contemporary Nato models in terms of armour, firepower and manoeuvrability. If the Soviets had invaded, Nato would have been unable to stop their larger conventional forces and would – sooner rather than later, have been forced to use nuclear weapons to avoid defeat. Attempts at US-German cooperation to produce a new tank – the MBT-70 – had failed miserably in the late 1960s. In the next decade both developed their own solutions to close the tank gap.

In 1979 the West German armed forces, the Bundeswehr, accepted the new Leopard 2 into service, followed three years later by the arrival in Germany of a new American tank, the M1 Abrams. Both were better protected, faster and had more effective guns than their predecessors. But Nato’s armoured doctrine still relied on quality rather than quantity to meet the Soviet threat.

In 1984, with the new generation of Nato tanks, including the British Challenger 1, in service, Soviet tanks still outnumbered their opponents by nearly three to one. Nevertheless, despite the appearance of a new Soviet “super tank”, the T-80, Nato was closing the tank gap. It also developed new fast-moving combined arms tactics, designed to strike deep into the attacking Warsaw Pact forces.

By the end of the decade Nato generals in West Germany could be confident that their tanks could blunt any Soviet invasion without needing to push the nuclear button.

In the event the cold war and the Soviet threat to western Europe collapsed with the Berlin Wall. The M1 Abrams and British Challenger 1 proved their mettle – and the validity of Nato armoured doctrine – in the deserts of Iraq and Kuwait during the 1991 Gulf War.

In the following decades Nato main battle tanks – the M1 Abrams, the Challenger 1 and 2, and the Leopard 2 – were deployed in peacekeeping operations in the Balkans or fighting insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan. Indeed, in George W Bush’s “New World Order” the main battle tank seemed a relic from the past. In the battle against terrorists and non-state actors, drones and “smart” bombs seemed much more relevant than 70-ton tanks.

Crimea changed approach

This changed suddenly and dramatically in 2014 with the Russian annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas. The US again sent their Abrams to Germany and German-made Leopard 2s were deployed to the Baltic states as part of Nato’s new enhanced forward presence battlegroups.

From 2014 until the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Nato states, including Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Poland and the Netherlands, expanded their tank forces and refocused from counterinsurgency to fighting a near-peer adversary on a conventional battlefield.

However, this decision pans out on the battlefield, it promises to hand Putin an important domestic propaganda victory – and one you can be sure he will exploit to the full.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about US and German tanks in Ukraine

Articles you may also like

Neutrality At All Costs: The Netherlands in WW1

By Fergus O’Sullivan World War 1 was a conflict that engulfed entire continents and swallowed up whole generations of men. It is the cause of trauma that has stayed with entire nations, even now, more than a century since it ended. However, for some countries the Great War is no more than a footnote in […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.