Reading time: 7 minutes

As the year 1922 dragged to a close, a weary public feared that it was doomed to die in doldrums. On the harrowing heels of World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic came a “summer journalistically so dull that an English farmer’s report of a gooseberry the size of a crabapple achieved the main news pages of the London metropolitan dailies.” One Lord Carnarvon remembered that “the public was in a state of boredom with news of reparations, conferences, and mandates, and craved for some new topic of conversation.”

And that’s exactly what they got. On November 26th, archaeologist Howard Carter and his patron—the same Lord Carnarvon—ventured inside the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun.

It was the archaeological find of the century—perhaps the greatest in the field’s entire history. Desperate for intrigue and escapism, the world was instantly enraptured. Said one contemporary writer, “to the past we must go as a relief from to-day’s harshness.” The ensuing craze, known as Tutmania, came to define the popular culture of the 1920s.

Fascination with ancient Egypt—”Egyptomania”–had struck the Western world before, dating back to antiquity. It came in waves, beginning with the Roman conquest of Egypt and rushing back into public consciousness with each major archaeological discovery. However, this intrigue was never so great—and never so widespread—as it became when Tutmania reigned supreme.

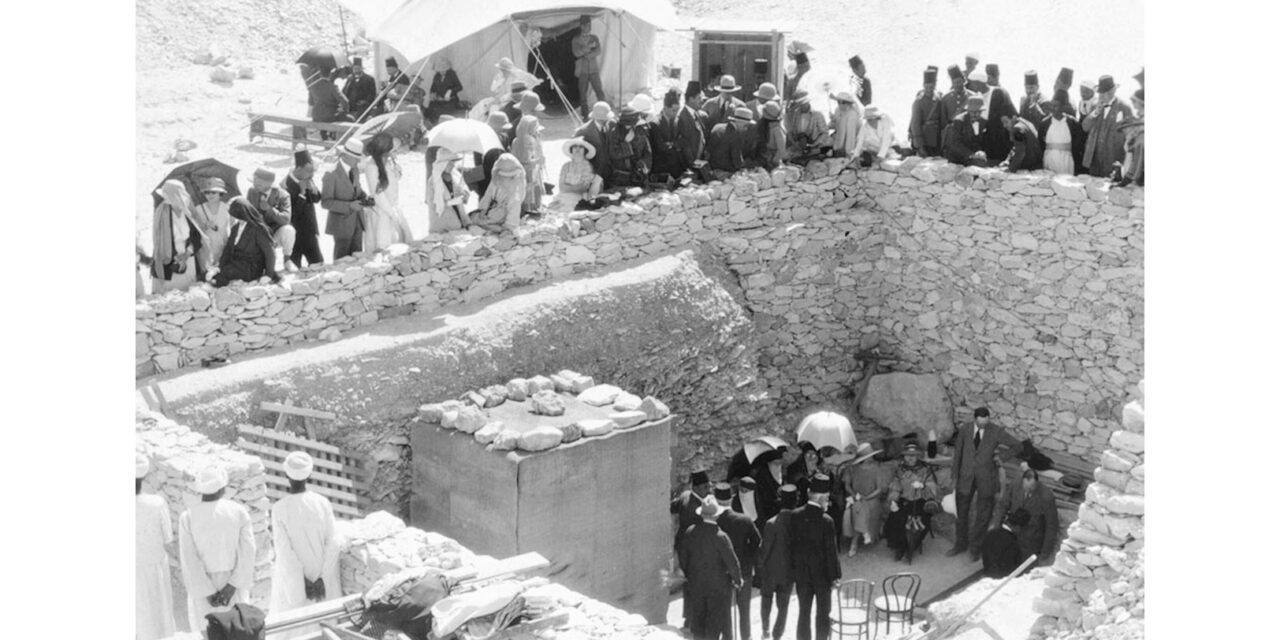

Press coverage of the excavation was aggressive, with newspapers battling for the rights to cover the story. Photographers—as well as ordinary visitors—camped outside the tomb, desperate to catalogue each artifact as it was removed. The rubbernecking was so intense that it was feared the tomb might collapse under the sheer weight of the assembled throng.

Thus, the public was bombarded with dispatches from the Valley of the Kings—all of which they eagerly consumed. And just as quickly as public interest caught fire, profiteering followed.

In time for Christmas of that year—less than a month after the discovery—all manner of Egyptian-themed chintz flooded the market. Biscuit tins decorated with ancient motifs, compacts of face powder—even sarcophagus-shaped mechanical pencils and pocket knives. One company attempted to market everyday lemons, with no connection to Egypt whatsoever, as “King Tut brand.”

But the commercial phenom was not limited to novelties or citrus. The New York Times reported that “nobody is watching the revelations from the tomb of Tut-ankh-Amen with greater interest than the… style designers, jewelers, cabinet-makers, workers in ceramics and even architects. The modern coiffure creator, beauty specialist, and cosmetic manufacturer are said to be equally interested.”

Indeed, much of the design aesthetic of the Art Deco style was influenced by ancient Egyptian art—and nowhere is this more prominent than in the iconic image of the flapper. The bobbed haircuts and drop-waisted dresses essential to that style strongly resemble those seen on the walls of ancient tombs.

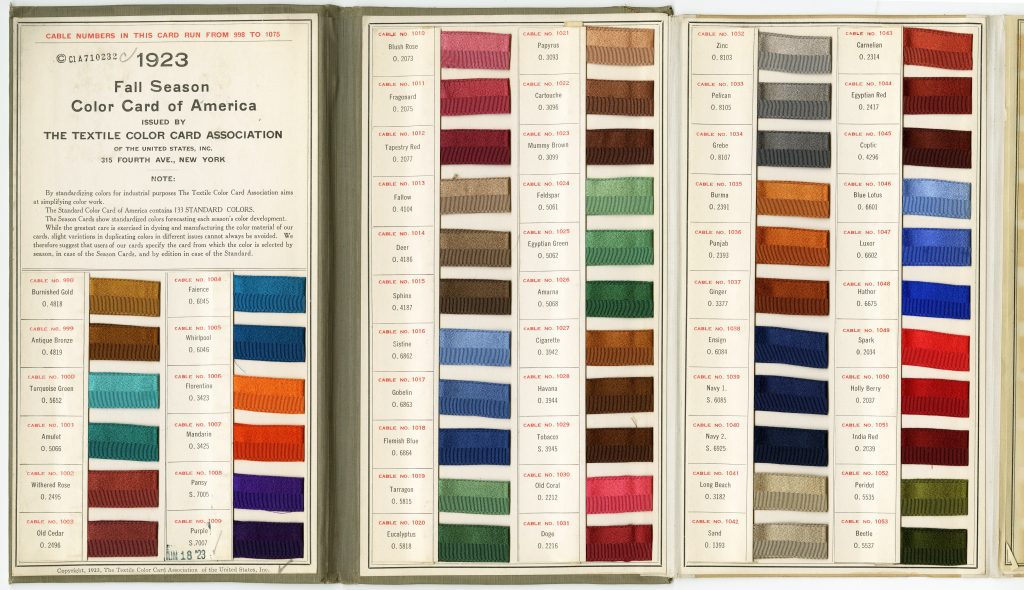

The fashion influences didn’t stop there. Dresses made from large swaths of fabric were called “mummy wraps,” and a fashion house in London developed the “Tutankhamen Over-Blouse,” a tunic cut affair with heiroglyphic embroidery. Even the very infrastructure of fashion was impacted by the trend—this 1923 sampler from the Textile Color Card Association of America features hues such as “Luxor,” “Papyrus,” and “Mummy Brown.”

The trend extended to architecture as well. Many buildings of the era feature Egyptian motifs in their elaborate relief carvings—a style called ‘neo-pharaohnism’–and the skyscrapers of the day are reminiscent of ancient obelisks in their shape. One particular architectural fad of the time was the Egyptian theater, movie theaters festooned with ancient Egypt-inspired designs. And of course, these theaters made an excellent venue to view the numerous Egypt- and mummy-themed films that came out following the discovery.

The popular music of the day was not exempt from Tutmania either—in 1923, the tune Old King Tut was released, followed closely by the similar Old King Tut Was A Wise Old Nut. Interestingly, the progress of the excavation can be tracked in the lyrical differences between the two songs.

Old King Tut was released very shortly after the discovery, and is largely speculative about the luxury in which Tutankhamun lived—and what manner of dancing girls he may have encountered—but by the release of Old King Tut Was A Wise Old Nut, more information about the tomb had been made public, and some references to actual fact were included in the lyrics. The line “they stored his tomb with beef and wine to help his journey on / today we find the beef is there but all the wine is gone” refers directly to the discovery of preserved meat and empty wine casks in the tomb.

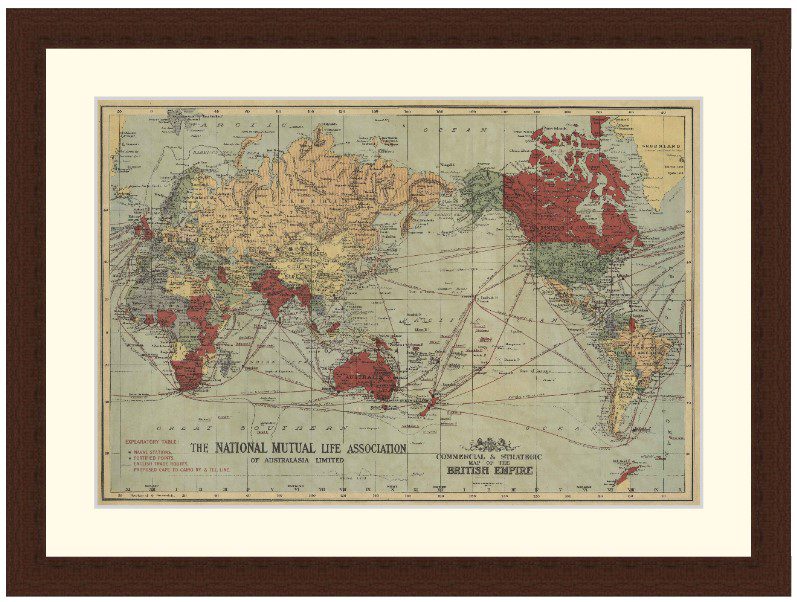

As spectacular as Tutmania was, however, the effects of Tutankhamun’s discovery were not limited to the Western world. The discovery came at a crucial time for Egypt, as well, which had gained its independence from England less than a year prior. At a time when their national identity was uncertain, Egyptian people—Copts and Muslims alike—began to take greater pride in their illustrious history, a movement which came to be known as Pharaohnism.

Some aspects of Pharaohnism mirrored those of Western Tutmania. The first Egyptian-made film, In the Country of Tut-Ankh-Amun, came out in 1923, and stories featuring ancient tombs and mummy’s curses were popular in Egypt as well as overseas. The difference between these stories was in their tone: while Western writers portrayed mummies and curses as frightening or tragic, Egyptian writers portrayed reanimated mummies as guardians of Egyptian culture, often reproaching foreign powers that had mistreated their nation. Additionally, the first Egyptology program at an Egyptian university was established in 1924, allowing the Egyptian people a stake in the excavation of their own ancient history.

Tutmania was not all harmless fun, however, nor a universally-positive driver of national pride. The continued looting of ancient tombs for the antiquities trade—and the trade in mummified human remains—was encouraged by the worldwide fervor. For the sake of illicit profit, many tombs were ransacked and many ancient people removed from their intended final resting places.

For good or ill, Tutmania’s effects were many and far-reaching. It is impossible to survey the aesthetics and popular culture of the 1920s without encountering some vestige of ancient Egyptian influence, be it in the music, fashion, architecture, or even the marketing of ordinary lemons. In this, perhaps, the pharaoh Tutankhamun has achieved genuine immortality.

Articles you may also like

Forgotten: Britain’s civilian mass prison camps from World War I

Reading time: 6 minutes

In 1914, Britain stood at the forefront of organising one of the first civilian mass internment operations of the 20th century. 30,000 civilian German, Austrian and Turkish men who had been living or travelling in Britain in the summer of that year found themselves behind barbed wire, in many cases for the whole duration of World War I.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.