Reading time: 6 minutes

If you go to the Surrey Hills of northwest Tasmania, you’ll see a temperate rainforest dominated by sprawling trees with genetic links going back millions of years.

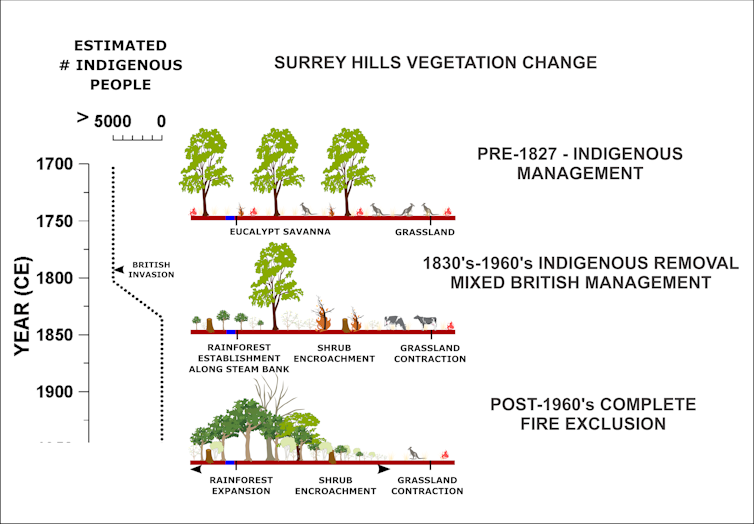

It’s a forest type many consider to be ancient “wilderness”. But this landscape once looked very different.

The only hints are a handful of small grassy plains dotting the estate and the occasional giant eucalypt with broad-branching limbs. This is an architecture that can only form in open paddock-like environments – now swarmed by rainforest trees.

These remnant grasslands are of immense conservation value, as they represent the last vestiges of a once more widespread subalpine “poa tussock” grassland ecosystem.

By Michael-Shawn Fletcher, University of Melbourne

Our new research shows these grasslands were the result of Palawa people who, for generation upon generation, actively and intelligently manicured this landscape against the ever-present tide of the rainforest expansion we see today.

This purposeful intervention demonstrates land ownership. It was their property. Their estate. Two hundred years of forced dispossession cannot erase millennia of land ownership and connection to country.

Myths of “wilderness” have no place on this continent when much of the land in Australia is culturally formed, created by millennia of Aboriginal burning – even the world renowned Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.

British impressions

Today, the Surrey Hills hosts a vast 60,000-hectare timber plantation. Areas outside the modern plantations on the Surrey Hills are home to rainforest.

On first seeing the Surrey Hills from atop St Valentine’s Peak in 1827, Henry Hellyer – surveyor for the Van Diemen’s Land company – extolled the splendour of the vista before him:

an excellent country, consisting of gently rising, dry, grassy hills […] They resemble English enclosures in many respects, being bounded by brooks between each, with belts of beautiful shrubs in every vale.

It will not in general average ten trees on an acre. There are many plains of several square miles without a single tree.

And when first setting food on the estate:

The kangaroo stood gazing at us like fawns, and in some instances came bounding towards us.

He went on to note how the landscape was recently burnt, “looking fresh and green in those places”.

It is possible that the natives by burning only one set of plains are enabled to keep the kangaroos more concentrated for their use, and I can in no way account for their burning only in this place, unless it is to serve them as a hunting place.

The landscape Hellyer described was one deliberately managed and maintained by Aboriginal people with fire. The familiarity of the kangaroo to humans, and the clear and abundant evidence of Aboriginal occupation in the area, implies these animals were more akin to livestock than “wild” animals.

A debated legacy

Critically, Hellyer’s accounts of this landscape were challenged later in the same year in a scathing report by Edward Curr, manager of the Van Diemen’s Land company and, later, a politician.

Curr criticised Hellyer for overstating the potential of the area to curry favour with his employers, for whom Hellyer was searching for sheep pasture in the new colony.

These contrasting perceptions are an historical echo of a debate at the centre of Aboriginal-settler relations today.

Authors such as Bruce Pascoe (Dark Emu) and Bill Gammage (The Biggest Estate on Earth) have been challenged, ridiculed and vilified for over-stating the agency and role of Aboriginal Australians in modifying and shaping the Australian landscape.

These ideas are criticised by those who either genuinely believe Aboriginal people merely subsisted on what was “naturally” available to them, or by those with other agendas aimed at denying how First Nations people owned, occupied and shaped Australia.

New research backs up Hellyer

We sought to directly test the observations of Hellyer in the Surrey Hills, using the remains of plants and fire (charcoal) stored in soils beneath the modern day rainforest.

Drilling in to the earth beneath modern rainforest, we found the deeper soils were full of the remains of grass, eucalypts and charcoal, while the upper more recent soil was dominated by rainforest and no charcoal.

We drilled into more than 70 rainforest trees across two study sites, targeting two species that can live for more than 500 years: Myrtle Beech (Nothofagus cunninghami) and Celery-top Pine (Phyllocladus aspleniifolius).

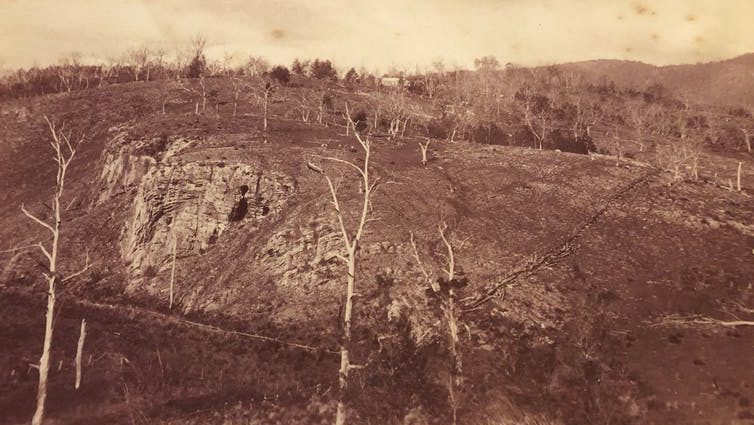

None of the trees we measured were older than 180 years (from 1840). That’s just over a decade following Hellyer’s first glimpse of the Surrey Hills.

Our data unequivocally proves the landscape of the Surrey Hills was an open grassy eucalypt-savanna with regular fire under Aboriginal management prior to 1827.

Importantly, the speed at which rainforest invaded and captured this Indigenous constructed landscape shows the enormous workload Aboriginal people invested in holding back rainforest. For millennia, they used cultural burning to maintain a 60,000-hectare grassland.

Learning from the past

Our research challenges the central tenet underpinning the concept of terra nullius (vacant land) on which the tenuous and uneasy claims of sovereignty of white Australia over Aboriginal lands rests.

More than the political implications, this data reveals another impact of dispossession and denial of Indigenous agency in the creation of the Australian landscape.

Left unburnt, grassy ecosystems constructed by Indigenous people accumulate woody fuels, in Australia and elsewhere.

Forest has far more fuel than grassland and savanna ecosystems. Under the right set of climatic conditions, any fuel will burn and increasing fuel loads dramatically increases the potential for catastrophic bushfire.

That’s why Indigenous fire management could help save Australia from devastating disasters like the recent Black Summer.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.