Reading time: 9 minutes

Sir Thomas More was among the leading statesmen of the Tudor period and his legacy has long survived his execution for treason in 1535. He has been portrayed on screen, stage and in literature and in his own time was at forefront of the English humanist movement.

By Neil Johnston, The National Archives

Sir Thomas More’s trial and execution was shocking in England (and beyond) and the events retain a special prominence, even among the many infamous events of Tudor England.

More publicly opposed Henry VIII’s claim that he was the Supreme Head of the Church in England. Defiant in the face of Henry and his ministers, More refused to take the Oath of Succession, because the preamble of the Act of Succession rejected papal authority over English ecclesiastical affairs. This was his final act of defiance.

In the years prior to his death, More had supported neither Henry’s divorce from Queen Katherine or his marriage to Anne Boleyn. Although More had enjoyed an uneasy truce with Henry and Anne, this eventually evaporated as Henry’s opposition to what he saw as papal intrusion into his affairs became more stringent.

A run of success

More had enjoyed an illustrious legal career before moving into public service. Although he entered Oxford University in 1492, his father, the lawyer Sir John More, wished him to follow in his footsteps. He recalled Thomas to London and enrolled his son as a law student at New Inn, before entering Lincoln’s Inns in 1496. Although only at Oxford for two years, More had fallen under the influence of academics pursuing new forms of learning, especially those who were leading the study of ancient Greek as a means of reinterpreting early Christian texts, including the Bible. This was to leave a deep impression on More, who sought to combine his study with the more worldly need to earn a living as a lawyer.

More merged his scholarly and legal interests to such successes that he was elected an MP in 1501, before being selected to serve as undersherrif of London in 1510. By this point, he had come to Archbishop Thomas Wolsey’s attention, who employed More as an intermediary and secretary for some years, during which he wrote his most famous work, Utopia. More formally entered royal service in 1518 when he was sworn as a royal councillor and thereafter he rapidly rose in Henry VIII’s esteem and was the king’s principal secretary from 1519.

Mixing legal, diplomatic and secretarial work, More’s career continued to blossom and he was promoted to the highest legal position in England when appointed to the lord chancellorship in October 1529, becoming one of the few laymen to hold this office. He also expanded the influence and remit of Chancery by modernising its functions, which reflected his desire to improve people’s lives through proactive public service. It must also be said that More used his positions to pursue and punish those he deemed heretics.

In opposition to the king

Despite his abilities, More’s personal politics increasingly conflicted with the king’s policies. Henry had failed to secure papal approval to annul his marriage to Katherine. More’s refusal to accept Henry’s claim that his marriage to Katherine had been illicit meant that he was demonstrably in opposition to the king. Inevitably, his resignation as lord chancellor followed in May 1532.

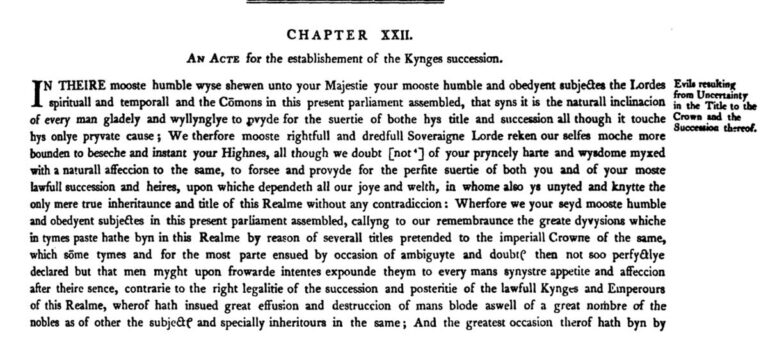

By this point, More had been eclipsed by new men who sought significant reforms to religious policy, led by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, and his ally Thomas Cromwell. In May 1533, Cranmer presided over Anne Boleyn’s coronation. In March 1534, Henry had Cromwell push the Act of Succession through Parliament, which legislated that Anne was the rightful queen and that any heirs were rightful successors to the Crown, through a clause requiring subjects to swear an oath that acknowledged the whole of the act. Several attempts were made to have More swear the oath, but each time he refused. His tactic was to remain silent.

For this, More was arrested in April 1534 and held at the Tower of London, where Cromwell and others again sought to secure his support for the language used in the acts of Supremacy and Succession. More remained silent, neither disowning the legislation nor supporting it. His silence, however, was unacceptable to a king who disliked any demonstration of opposition. Up to four attempts were made to have him swear the Oath of Succession but More was adamant that he would not.

But politics continued to confound More’s position. In November 1534 Parliament reconvened and passed the Act of Supremacy that declared Henry and his lawful heirs as the head of the Church in England. Parliament also passed an additional Treason Act and it was this that was used to condemn More.

Trial as performance

Having languished in the Tower for over a year, More was eventually charged with treason in May 1535. But before we think about More’s trial, it is worth remembering that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, treason trials were performative: the Crown used them to demonstrate that challenges to its authority would be met with the full force of the state.

In the early modern period, treason trials held at the Court of King’s Bench were political acts where the court officials were expected to secure a guilty verdict. In politically significant cases, a special court (called a commission) was established to try the accused. It usually assembled at the Court of King’s Bench in Westminster Hall or some other imposing building such as the Guildhall in London.

A Grand Jury of commissioners was empanelled, usually made up of the senior office holders of the state and presided over by men such as the Lord Chancellor of England or the Lord Chief Justice of the Court of King’s Bench, who were joined by the Chief Justices of the Court of Common Pleas and Exchequer, and their puisne (junior) judges. The Crown’s law officers, the solicitor general and attorney general will have joined them, as well as some of the senior nobles of the kingdom. This was an imposing body for any person to face.

A jury of peers would also be empanelled to determine the evidence presented to the court. The procedure differed significantly to modern trials. Guilt was assumed from the outset. The accused was not permitted to know the charges before the trial commenced, they could not call witnesses, nor could they submit evidence. They could challenge the court, and many did, but they were denied the support of a legal counsel. They were entirely alone against the might of the state apparatus.

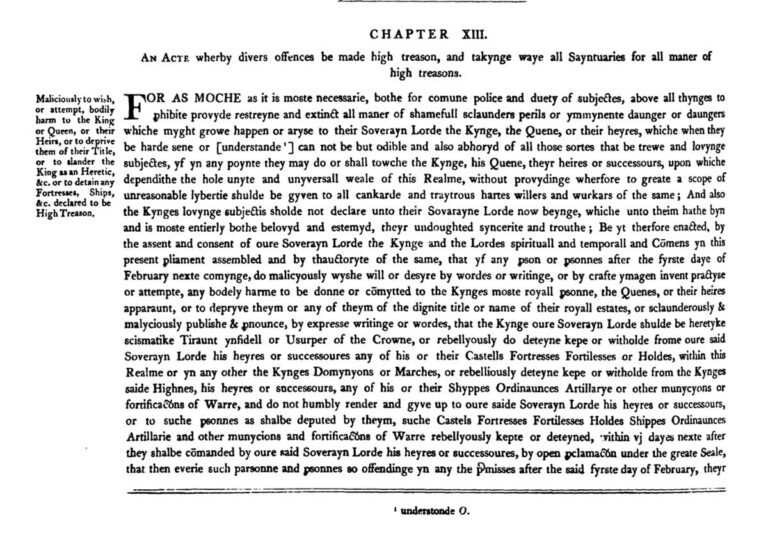

Despite all of this, treason trials could often be perilous for the Crown when the accused were tried under the 1352 Treason Act, especially with the need to prove that the accused had ‘compassed and imagined’ the downfall of the monarch. But this was not More’s crime.

More’s conviction

Under the terms of the 1534 Treason Act (26 Henry VIII, c 13), which came into force in February 1535, one section was a direct response to More’s silence: anyone who did ‘deprive them [the king or queen, or their legal heirs] of the dignitie title or name of their royal estates’ was a traitor. Silence, in this instance, was seen as overtly denying the king his title of supreme head of the Church of England. And that was treasonous.

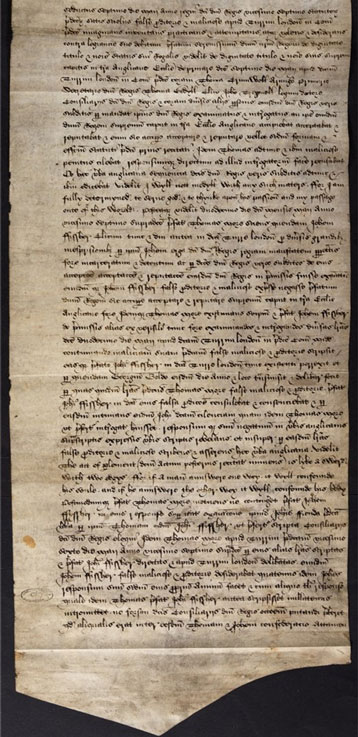

More was brought to trial on 1 July 1535 and the outcome was never seriously in doubt. The charges were listed on the indictment: that in not swearing the oath of succession More was in violation of Henry’s Treason Act by depriving the king of his royal dignity; that he had been in ‘confederacy’ with a fellow prisoner in the Tower, Bishop John Fisher; and in the presence of Richard Rich, the solicitor general, he had overtly (but without malice) rejected the king’s title on 12 June. More disputed each of these before the jury and his poise was noted in the face of certain death.

Having been dismissed to consider the evidence, the jury took just 15 minutes to deliberate. Upon returning to the court, they pronounced More’s guilt, although it is unclear if he was convicted on all charges or just one.

It was only now that More revealed his thoughts. Condemning the parochialism of Henry’s motives in declaring his supremacy, as well as Parliament and the bishops who supported Henry, More said, ‘For of the aforesaide holy Bishopps I have, for every Bisshopp of your, above one hundred; And for one Councell of Parliament of yours, I have all the councelss made these thousande years. And for this one kingdome, I have all other christian Realms.’

Soon after he was lead away, having been sentenced to a traitor’s death. He was executed on 6 July 1535 by beheading. His body was likely buried in St Peter ad Vincula at the Tower of London.

A growing legacy

Whether or not the charges would have been enough to condemn More under the 1352 Treason Act is a moot point. In 1535, he was guilty of denying the king his rights as the most high-profile opponent of Henry’s claim to supremacy over the Church of England. In the short term, Henry and his counsellors had faced down a formidable opponent. They also swiftly banned publications about More’s life or trial. These restrictions were relaxed over the rest of the sixteenth century and More’s complicated life fascinated many people.

Beyond England, tributes to More were swift and he was quickly acknowledged as a martyr. His legacy has continued to grow, both because of his published works, but also him dramatic death. While he had made his name as a writer during his own time, his reputation as a public official and pursuer of heretics remains controversial to this day. Canonized in 1935, Pope John Paul II recognised Sir Thomas More as the patron saint of statesman and politicians in 2000.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about Treason to the Crown

Articles you may also like

A World War II battle holds key lessons for modern warfare

Reading time: 6 minutes

Between Aug. 7, 1942, and Feb. 9, 1943, U.S. forces sought to capture – and then defend – the Pacific island of Guadalcanal from the Japanese military. What started as an amphibious landing quickly turned into a series of massive air and naval battles. The campaign marked a major turning point in the Pacific theater of World War II. It also revealed important lessons about the nature of warfare itself – ones that are particularly relevant when planning for conflict in the 21st century.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.