Reading time: 10 minutes

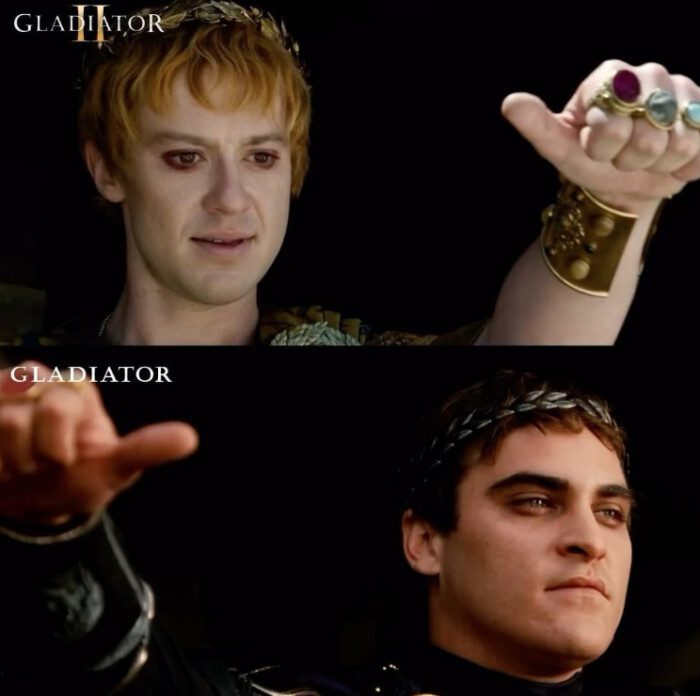

At first glance, it could be said that few people have popularized Ancient Rome in recent decades as much as Ridley Scott with his films Gladiator I and II. However, can we still maintain this claim if almost everything we see in Scott’s films is in complete opposition to what Ancient Rome actually was? Of course, Scott’s films are not documentaries, and many historical inaccuracies can be attributed to artistic freedom and the need for dramatization. Despite this, if the entire plot contradicts the very nature of Rome, perhaps the story should have been set in another historical period. Otherwise, anti-Roman themes are being marketed as Roman. While it is true that many of Scott’s choices arise from a lack of historical knowledge and understanding, it cannot be overlooked that through his films (not just Gladiator), he attempts to promote his own political ideology, which, in many ways, is part of the American mainstream but in no way reflects Roman ideals.

By Roberto Golovic

The 2000 Gladiator is undoubtedly a cinematic masterpiece; however, the main driver of the plot is “a dream that was Rome,” as Marcus Aurelius announces at the beginning of the film his desire for Rome to return to being a republic after his death. These words form the basis of the unimaginative and derivative Gladiator II from 2024, which could also be considered a soft reboot of the first film. This will sound strange to many, but the Roman Republic never truly fell – at least not until Rome itself fell.

How is this possible? Ridley Scott didn’t invent the fall of the Roman Republic, but perhaps he too was under the wrong influence – perhaps (the otherwise excellent) I, Claudius series, based on Robert Graves’ novel. In this work, every positive character, including Claudius himself (played by Derek Jacobi), laments the supposed fall of the Republic and mourns the time before the empire was established. The apocalyptic sense of the Republic’s demise was also contributed to by one of the best podcasts on this topic, Dan Carlin’s Death Throes of the Republic. At the same time, if you went to a library or a well-stocked bookstore, you might find books titled The Fall of the Roman Republic by Plutarch or Cassius Dio. However, none of the ancient historians ever titled their works ‘The Fall of the Roman Republic.’ This title is a later invention, often used by modern editors or historians to organize or describe passages from their works that deal with the period leading up to the establishment of imperial rule.

However, when Octavian Augustus became the first Roman emperor, he did not abolish the Roman Republic, but rather changed its form of governance. The system in which political power ultimately rested with the consuls transformed into one where it was concentrated in the hands of the imperator. When Augustus addressed the Senate and claimed he had “restored the Roman Republic,” these were not cynical words from the destroyer of the Republic, as often interpreted today, but rather a straightforward declaration that he had unified the Roman state, which had been torn apart by years of civil war. Both the senators and the citizens of Rome were aware of this, and their lives did not change significantly with the (partial) change in political organization, whether they lived in the capital or in the provinces. The state continued to collect taxes, the courts continued to enforce the law, the Senate continued to pass laws, consuls and tribunes were still elected, and so on.

The reason you are probably unaware of this is that in your understanding, “republic” is seen solely as a political system. From the perspective of a modern-day person, Rome transitioned from the democratic period of the Republic to the monarchical era of the Empire. However, the Roman Republic not only survived the “fall of the Republic,” meaning the establishment of the Empire, but it also endured the fall of Rome itself. Byzantium (the Eastern Roman Empire) preserved the concept of the Roman Republic in its New Rome (Nova Roma), Constantinople. While the Latin term res publica was increasingly replaced by the Greek politeia of the same meaning, the continuity of the Republic remained evident. This is clearly demonstrated in the Novels of Justinian (Novel Constitutional Decisions), written in both Latin and Greek in the mid-6th century. In these documents, republic/politeia is used as a term describing a comprehensive social order, within which the emperor rules and administers justice.

That the Roman Republic does not imply any specific form of government can also be concluded from Cicero’s seminal work, titled On the Republic (De re publica). Written several decades before the establishment of the Roman Empire (an event Cicero did not live to see), this work explicitly states that the republic can have different political systems: monarchical, aristocratic, or democratic. In On the Republic, Cicero examines the advantages and disadvantages of each form of governance, particularly emphasizing his preference for a combination of all three elements. In his view, this is what characterizes the Roman Republic: monarchical in the figures of the consuls, aristocratic in the Senate, and democratic in the popular assemblies.

If the Roman Republic is not a political system, then what is it exactly? This is a difficult question to answer, though it would be tempting to say that for the Romans, the Republic was synonymous with the state. However, this would be an overly simplified claim, as the Republic, as an idea, was something more than that. A literal translation of the term res publica would be “public matter,” suggesting that it pertains to something involving all citizens. This awareness existed among the Romans from the very beginning of the Republic until its fall in 1453. Therefore, the survival of the Republic was not limited to mere terminological and ideological terms, but also had very practical implications. Unlike their Eastern and, in the Middle Ages, Western contemporaries, even the late Roman Empire maintained a special relationship between authority and the people.

In the New Rome, just like in the Old, the Hippodrome was located next to the imperial palace, and the emperors often used it to convene large public assemblies. At these gatherings, they tried to generate support for a particular decision or simply gauge the people’s sentiment on a specific issue. For example, Emperor Anastasius I, in the early 6th century, handed his diadem to the rebellious masses in the Hippodrome and offered his resignation. Unlike Anastasius, whose resignation was not accepted, Emperor Michael V was overthrown when he attempted to do the same about 500 years later. Emperor Alexius III, at the turn of the 12th to 13th century, addressed the “Senate, Church, and people” of Constantinople with the news that he had managed to reduce the tribute (so called “German tax”) owed to German King Henry VI, from 5,000 to 1,600 pounds of gold. However, the public reaction was so negative that the emperor soon reversed his decision and decided that the tribute should not be paid at all.

Essentially, the actions of later emperors do not deviate substantially from the practices of the Republic during the time of Caesar and Augustus. Both ascended to their positions through approval in the Senate and popular assemblies, with the overwhelming support of the Roman populace. Until the Crisis of the Third Century, each emperor assumed power only after the Senate enacted a special law, lex de imperio. This law formally granted the new emperor legal authority, including the transfer of imperium (executive power) and other rights associated with the imperial office. In other words, even though the emperor ideologically enjoyed the status of a deity in the pagan era, and of God’s chosen representative in the Christian period, he was always, first and foremost, a public servant. His legitimacy could be questioned by poor performance in office, which often led to his overthrow – more often than not accompanied by varying degrees of violence.

While dynastic succession often provided the most straightforward path to the throne, it was by no means a surefire guarantee of power, as contrasted with the practices in the Western kingdoms. It was not uncommon for a Roman army to decide it had a better candidate for the purple. However, if the population of the capital sided with the reigning emperor, he would retain power. On the other hand, if they turned their backs on him and allowed an usurper to enter the city, a new emperor would soon be seated on the throne.

This relationship with their monarch was a constant source of astonishment among other medieval European monarchies, which did not have the Roman Republic as the cornerstone of their political ideology. That dynastic lineage is not the sole, or even the main, source of legitimacy is a continuity from the earlier Empire. It would seem that Ridley Scott had some notion of this concept, since in Gladiator I, Marcus Aurelius bypasses his son Commodus when selecting his successor, promising the purple to the more capable and honourable Maximus. However, in Gladiator II, the same concept is completely discarded, and Marcus Aurelius’ grandson is mentioned as the “prince of Rome,” possessing “blue blood”- terms that would have meant absolutely nothing to Romans of that time.

In summation, referring to the Roman Empire as a ‘Republic’ may seem counterintuitive to most as, since the 18th century, monarchies and republics have been viewed as mutually exclusive forms of government. This has been further reinforced by modern (but not Roman) conventions of using the terms ‘Republic’ and ‘Empire’ to differentiate between two phases of Roman history. However, by projecting our contemporary worldviews onto the past, we break one of the fundamental rules of history. For the Romans, ‘republic’ was a far more complex concept that did not depend on the form of government. The Roman Republic had an empire long before it had an emperor, and even after it gained an emperor, it did not cease to be a republic. The changes that occurred in the Roman state and the roles of its institutions over the centuries were not the result of sudden political upheaval. Instead, they reflected a gradual process of adjustment and evolution – sometimes influenced by the needs of the elites, sometimes by the demands of the people, and often by external factors.

It is not uncommon for political terms to change their meaning over time or across geographical regions. The American understanding of a nation has little in common with how that term is interpreted in Europe. What was considered liberal a century or two ago would be seen as conservative today. While the title of despot was once a coveted position in Byzantium, today it is synonymous with a tyrant. However, the term tyrant itself had no negative connotations among the ancient Greeks in the 5th century BCE, it simply referred to an autocratic leader who rose to power outside the traditional framework of aristocracy or hereditary rule.

With that in mind, we should recognize that the Roman Republic is far older than today’s concept of a republic, and it should not be diminished by retroactive interpretations, such as those propagated by Hollywood, among others. Ironically, by using Rome to promote his own political ideology, Ridley Scott (who is not alone in this, but is the most vocal) has, through his works, aligned more closely with the decadent Roman emperors he seeks to criticize – emperors who abused their positions to satisfy their personal whims.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

For further reading on the continuity of the idea of the Roman Republic in the later Roman Empire, one should refer to The Byzantine Republic: People and Power in New Rome by Anthony Kaldellis.

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.284

1. What was the purpose of the 1948 Marshall Plan?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

This article is published with the permission of the author. If you would like to reproduce it, please get in touch via this form.