Explorer, Scientist, and Humanitarian Hero

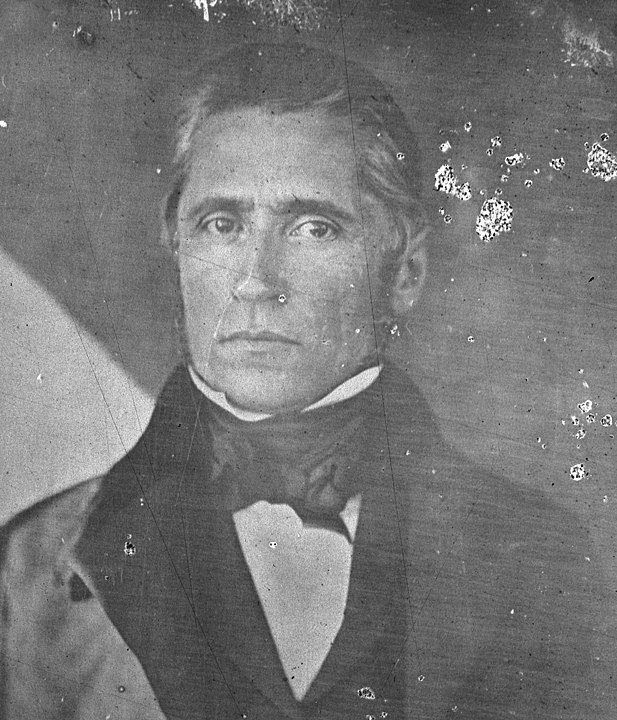

By Caitlan Hester. Sir Paul Strzelecki (1797-1873) spent over four years exploring 7,000 miles of mainland Australia and Tasmania on foot.

He found gold and summited Australia’s highest mainland peak. He mapped New South Wales and set up irrigation channels in Tasmania.

These incredible contributions to Australian agricultural and economic growth would later earn him a knighthood.

Strzelecki was also a humanitarian, philanthropist, environmentalist, nobleman, scientist, and businessman. His research included geology, palaeontology, meteorology, mineralogy, geography, ethnology, biology, and agricultural science.

He could have retired early as a famed explorer and scientist. But he went on to selflessly serve over 200,000 children in Ireland during the Great Famine.

Early Life in Prussia

Paul (Pawel) Edmund de Strzelecki was born in Prussia-controlled Poland on July 20, 1797. He was the youngest of three children, born to noblemen.

Paul’s father died in 1801 followed by his mother in 1807. In response to Paul’s mother’s death, his aunt sent him to school in Warsaw at 10 years old. He remained there until moving to Cracow at the age of 17.

Paul would return to the family estate and be reunited with his brother and sister 4 years later.

Military, Tutoring, Business, and Loss

As a young man, Strzelecki spent a stint in the Prussian cavalry before becoming a tutor.

Paul (23) fell in love with his pupil’s sister, Adyna (15), whose father rejected Strzelecki’s proposal. Historians say it’s conjecture, but rumour insists the young couple tried to elope, and their plan was thwarted.

Paul and Adyna would exchange letters for over 40 years, but never marry.

Strzelecki packed his bag and went abroad. He began to travel around Europe; Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Switzerland, and Italy. And he began to develop his interest in the sciences, often self-taught.

While in Italy, he met and befriended the Polish Count Francis Sapieha. They became close friends and the Count made Strzelecki the business administrator of his estates. He excelled at his work and the two formed a strong bond.

Unfortunately for Strzelecki, the Count died in 1829, and Strzelecki found himself in a legal dispute over the will. Once again, Strzelecki sought travel and the natural sciences.

The Natural Sciences and World Travel

Strzelecki travelled to France, Africa, and then England.

He remained in England for a few years, acquiring knowledge of geology, geography, and agricultural sciences.

In June of 1834, he left for North America where he conducted ethnographic research about the life and culture of indigenous tribes. He studied the geological features and agricultural practices in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean.

He spent two years studying geology and meteorology in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile.

Travelling on British ships along the coasts of the Americas, he became opposed to the slave trade. Strzelecki’s writings pleaded for humanity and land rights for indigenous people, black people, and people of colour.

He sailed the Polynesian islands and then carried out the first geological survey ever conducted in New Zealand.

Australia Expeditions – Strzelecki’s Claim to Fame

In April 1839, Strzelecki landed in Australia, where he would spend four years exploring, mapping, and making a name for himself.

He covered over 7,000 miles of New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania on foot with the help of Aboriginal guides.

Strzelecki entered new territories with permission from the Aboriginal people and never by force.

Gold, the Grose River, and the Blue Mountains

Shortly after arriving in Sydney, Strzelecki met Governor George Gipps. It was a meeting that would initiate a 3-month journey along the Grose River, through the Blue Mountains.

He discovered gold and silver in the area of Bathurst but Governor Gipps was fearful that a gold rush could turn violent. So, he asked Strzelecki to conceal his findings. Because of this delay, Strzelecki’s claim to the discovery of gold would later be contested.

Mt Kosciuszko, Gippsland, and a Close Call

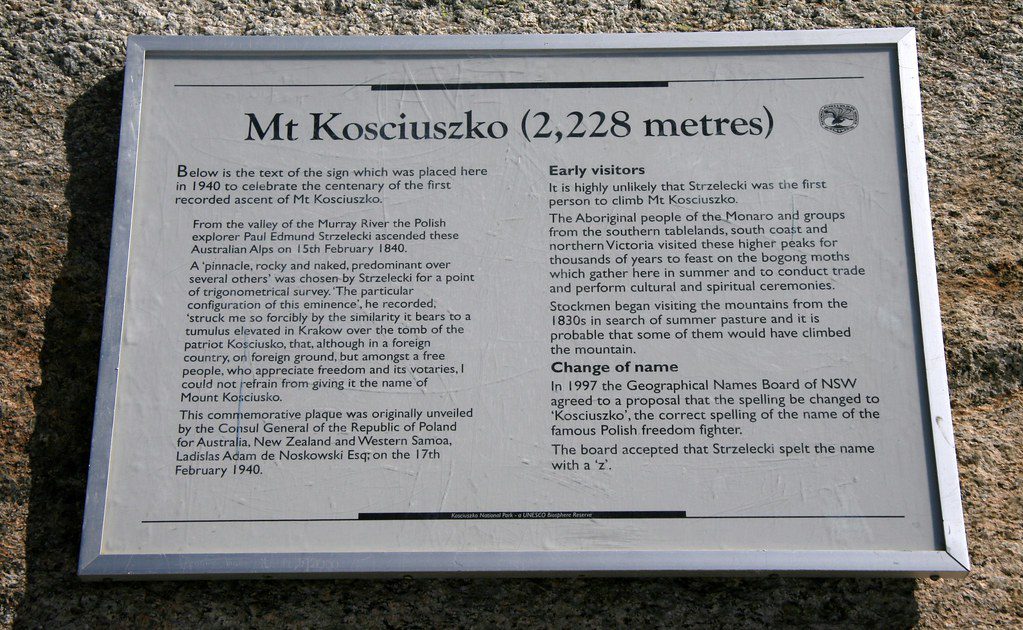

In 1840, Strzelecki, with a team of explorers and Aboriginal guides ventured into the Snowy Mountains where they identified Australia’s highest mainland point. He became the first European to take the summit. He named the mountain Mt Kosciuszko, after the Polish-Lithuanian military leader and freedom fighter, Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

The team then travelled south through Eastern Victoria in the area that he dubbed Gippsland, for the governor. Mt Kosciuszko brought Strzelecki fame, but Gippsland offered him notoriety, as Gippsland was ripe for farming and emigration.

Strzelecki’s most famous expedition almost ended in tragedy after passing the La Trobe River. The party had to abandon everything and return to Melbourne. They were able to survive with scarce food for nearly three weeks thanks to their Aboriginal guides, Charlie Tarra and Jackey.

He later organized expeditions of Liverpool Plains, Newcastle, and Port Stephen.

Irrigation and Coal in Tasmania

Strzelecki spent his last two years in Australia in Tasmania. He climbed the highest peak of Flinders Island and established a laboratory in Launceston in May 1840.

He discovered coal in Northern Tasmania and also became friends with Governor Sir John Franklin. Strzelecki helped Franklin plan irrigation channels for the agricultural areas hit by drought.

They established The Tasmanian Society of Natural Sciences and The Tasmanian Journal.

The Publication That Shaped Southeast Australia

In April 1843, a 45-year-old Strzelecki left Australia to return to London. On his way to London, he visited Bali, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Cairo.

Back in England he became a British citizen and published Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Dieman’s Land. It was the first detailed, scientific book about Australia.

He also published the first map of Gippsland as well as the first geographical map of Eastern Australia and Tasmania. His publication and maps helped open Victoria for agriculture and emigration.

For this, the Royal Geographical Society awarded him the Gold Founder’s Medal. Later in life, he would also be knighted by Queen Victoria for this work.

Innovative Humanitarianism in Ireland

Meanwhile, in the 1840s, the Whig party wasn’t taking action regarding the European potato blight. The situation was escalating, leading to the disaster of the Great Famine in Ireland.

Hundreds of thousands died of starvation and disease with hundreds of thousands more fleeing the country.

The British Relief Association Appoints Strzelecki

A group of English bankers formed a famine relief fund called the British Relief Association. They appointed Strzelecki as their main agent and placed him in charge of the distribution of supplies in Western Ireland.

When he arrived in January 1847, he was horrified by the humanitarian crisis he witnessed.

Aid Arrives at Schools and Revolutionizes Relief Plans

Before Strzelecki’s plan, aid was handed out in public spaces. Children were often overpowered in the chaos of the starving riot grabbing for pieces of food.

Strzelecki made this observation and developed a groundbreaking relief plan. He would give the starving children food rations directly through the schools. Strzelecki’s plan fed the children, gave them clothing, and provided hygienic supplies.

Despite contracting typhoid while in Ireland, Strzelecki dedicated himself to hunger relief. It’s estimated that at the peak of the program, around 200,000 children were being fed.

The Lasting Impact of Strzelecki’s Plan

But Strzelecki’s plan not only fed and clothed children. It also kept children in schools. It allowed parents to get back on their feet. And it kept families out of the infamous, disease-ridden workhouses.

Strzelecki also helped impoverished Irish families seek new lives in Australia.

Strzelecki Orders the Destruction of His Life’s Work

Throughout the rest of his life, Strzelecki continued to contribute to various causes as a philanthropist.

He died in October 1873 in London at the age of 76. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery but was moved to Poland in 1997, where he was buried at the Church of St. Adalbert in the Crypt of Eminent Poles.

Despite his long life and many accomplishments, much of Sir Paul Strzelecki’s life remains shrouded in mystery.

In his will, he requested that he be buried in an unmarked grave. And he ordered the destruction of all his journals, notes, letters, reports, and papers.

Conclusion – Strzelecki the Enigma

Unfortunately, because Strzelecki ordered the destruction of his records, everything we know about him comes from secondary sources.

One of his biographers, Paszkowski, wrote “it was impossible to write a satisfactory biography of Strzelecki,” despite 40 years of research.

![Sir Paweł Edmund Strzelecki [Memorial Plaque Clerys Department Store]-113492](https://historyguild.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Sir-Pawel-Edmund-Strzelecki-Memorial-Plaque-Clerys-Department-Store-113492.jpg)

He was a fascinating character often described as social, charming, and intelligent. But he was also a secretive, wandering loner who never married.

Before reaching acclaim for his work in Australia, Strzelecki had been neither wealthy nor deprived. He was thought to have savings in a French bank, but he funded his travels by selling rocks, fossils, and minerals. His many well-to-do friends also offered their hospitality which offset his travel costs.

A self-taught geologist, determined explorer, and selfless humanitarian – this Polish nobleman turned English gentleman saved over 200,000 Irish children and influenced modern-day Australia.

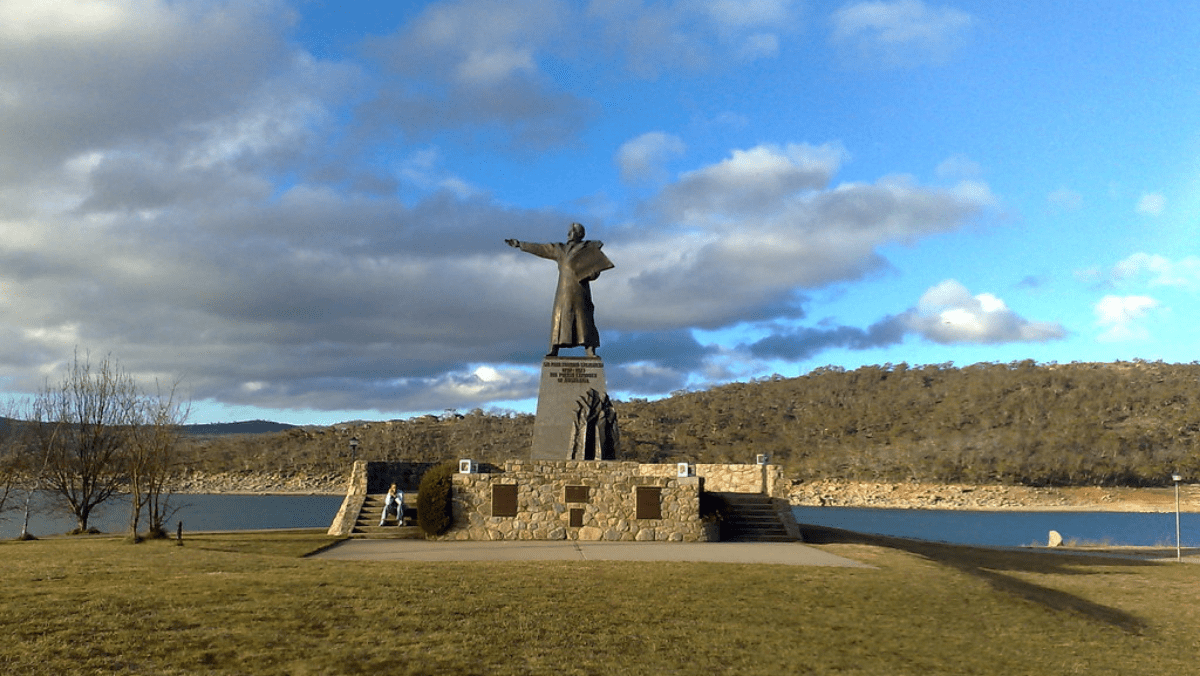

He is remembered with places named after him, statues and recognition in Australia, Ireland and Poland. He even has a bike tour named in his memory, the Strzelecki Tour.

Articles you may also like

Battle of 42nd Street – Anzacs Proving Germany Could be Beaten

Morale can make all the difference on the battlefield. On the 27th May 1941, with the Greek island of Crete close to loss and the Allies in full retreat, a 12 minute moment of madness by Australian and New Zealand troops proved that aggression and bravery could overcome Germany’s elite troops. By Richard Shrubb. Background […]

Hi all,

I invite you to the English version of this http://www.mtkosciuszko.org.au website. You will find reliable information related to the conquest of Mt Kosciuszko the highest peak of Australian mainland, and about Paul Edmund Strzelecki the explorer who gave the mountain its name.