Reading time: 14 minutes

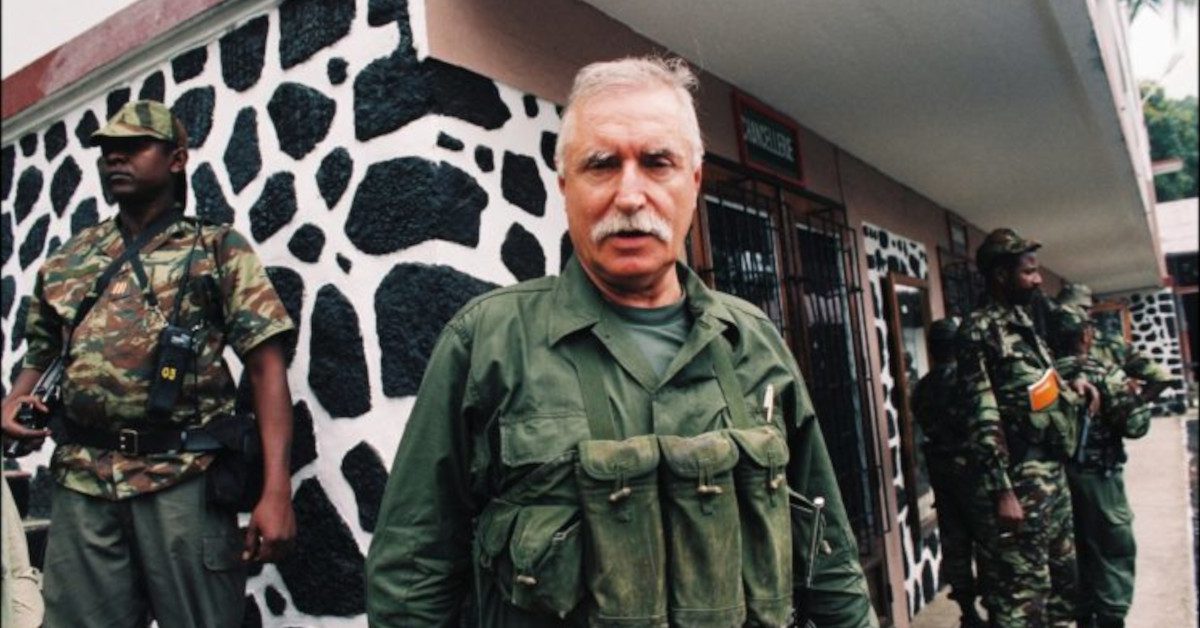

Bob Denard had not quite reached his 32nd birthday when a newspaper article caught his eye. It was a profile on the foreign mercenaries fighting for Moïse Tshombe’s breakaway state, Katanga, in southern Congo, and it contained a photograph of the only Frenchman in Tshombe’s service.

“His name was Antoine de Saint-Paul,” Denard recalled, “and I envied him.”

By Morgan W. R. Dunn

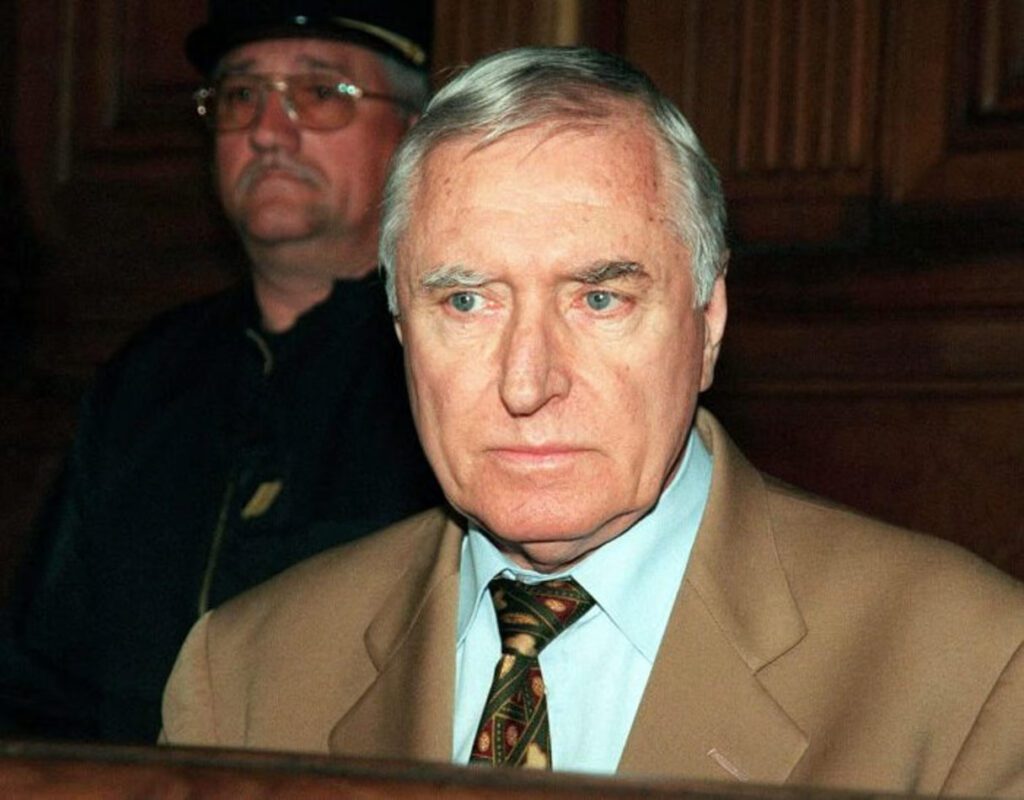

Thus began a thirty-year career as a soldier-for-hire in over a dozen conflict zones across Africa. By the end, Denard had served as an unofficial privateer of the French government, aroused endless outrage (and from some, admiration), and established his own domain in the Comoros. This was the career of Bob Denard, “the corsair of the Republic.”

A Soldier’s Childhood

Born Gilbert Bourgeaud in Bordeaux on 7 April 1929, Bob Denard was just 10 years old when German troops entered his village of 500 people. The Germans, he later said, “appeared magnificent to our kids’ eyes: beautiful, sporting, merry, with their marvellous machines, tents, sidecars, guns… we followed their tracks to collect their spent cartridges, which we filled with powder, so that we too could play at war.” Already, he wanted to be a soldier.

In 1945, the 16-year-old Denard faked his age and joined the French Navy as an apprentice mechanic. His naval career would last eight years. In that time, he saw savage fighting in the Mekong Delta during the First Indochina War, almost lost a leg to an infected wound, and was promised the Croix de Guerre, only to have it taken away after a drunken rampage in a Vietnamese bar.

After eight years of service, Denard had only reached the rank of quartermaster, equivalent to an army corporal. Determined to become an officer, he believed class and regional prejudice in the navy would always prevent him from achieving his dream. When his contract ended in 1953, he quit.

Denard was left a bitter and fervently anti-communist man. His military career seemingly over, Denard joined a construction company in French-ruled Morocco. He married and had a son, and later joined the Moroccan police.

In 1954, Denard was arrested for allegedly taking part in a plot to assassinate Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France. Released after 14 months in prison, he moved to Paris with his family, worked as an appliance salesman, and occasionally as hired muscle. In December 1960, meeting some friends in a bar, he told them he was “bored shitless.” That evening, he spotted the photo of Saint-Paul taken in Katanga, a breakaway state in the south of what, until June 1960, had been the Belgian Congo.

“Denard disappeared into the night,” wrote his biographer Samantha Weinberg, “and the next [his friends] heard of him was six months later… dressed as a dashing officer of the Katanganese gendarmes and sporting the beret of the paracommandos.”

In the World of the Awful Ones

Denard had no luck joining Colonel Roger Trinquier, head of a mission to supplement and train the Katangese Gendarmerie. Instead, he flew to Brazzaville in what had, until six months earlier, been the French Congo. After a chance meeting with a Katangese politician, Bob Denard was commissioned a sous-lieutenant in the Katangese Gendarmerie, with a salary of 13,000 Belgian francs a month – a fortune at a time when a French minimum wage worker could expect to earn less than 300 francs in the same time.

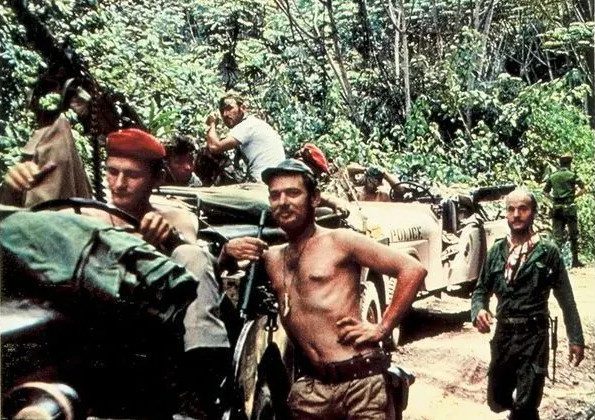

Hundreds of foreign mercenaries found work during the Congo Crisis. These men were known to the Congolese as les affreux – “the awful ones,” because, explained one Belgian mercenary, “we like to risk our lives. Especially because risking your life can pay big when it’s tough.” Some were veterans of European armies. Others were simply men looking for excitement.

Denard became second-in-command of Groupe Mobile C and earned a chance to lead his unit in a parade in Tshombe’s honor, during which he “mixed his white and black troops together for the march down an Elisabethville boulevard. The Katangese crowds applauded. Belgians looked shocked. At a reception afterwards, Tshombe congratulated Denard on his enlightened leadership and gave him command of a unit in Albertville.”

But soon after his triumphal march, on 28 August, United Nations peacekeepers began Operation Rumpunch, an effort to scour the Congo of foreign mercenaries. It only resulted in 300 arrests; Denard was among them.

The Corsair of the Republic

No sooner was Denard in Brussels than he turned right around. On 15 September, “wrapped in bandages and carrying papers identifying him as a Belgian civilian injured crocodile hunting,” he turned up at Colonel Faulques’s headquarters once more.

Denard, now leading a half-Katangese section of 30 men armed with mortars in jeeps having “arrived in the Congo with the two red wool stripes of a corporal,” was soon promoted to captain, and had even succeeded Faulques by December 1962. He earned a reputation as a tough leader who would fight for his men’s pay. But just weeks later, exhausted Katangese forces finally surrendered to UN peacekeepers.

After Katanga, Denard spent part of 1963 training royalist rebels fighting in North Yemen’s civil war. The following year, he was invited back to the Congo and made a colonel. He spent several years combating Simba rebels, supporters of the murdered Congolese prime minister Patrice Lumumba.

In 1967, Denard became involved in a plot with another mercenary leader to overthrow Congolese president Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. Wounded and evacuated to Angola, he attempted to rejoin the fight by crossing the border with his men mounted on bicycles, but the Mercenaries’ Revolt collapsed when Denard’s column withered under enemy attention.

Spending the rest of the 1960s in Kurdistan, Angola, Gabon, and the Nigerian breakaway state of Biafra, by the close of the decade, Denard’s reputation was tarnished by failure. To clean it up, he needed a new venture. Benin fell into his lap.

Operation Shrimp

Benin, formerly the French colony of Dahomey, had only been independent for 12 years when a young leftist army officer, Major Mathieu Kérékou, seized power in 1972. Kérékou nationalised major French companies in Benin and unleashed a wave of violence against dissidents.

A man like Denard was an invaluable asset to a man like Jacques Foccart, chief advisor to President Charles de Gaulle on French African policy and the president’s agent when it came to getting African leaders to toe the French line. Foccart’s thumbprint was on a coup attempt against Kérékou backed by the leaders of Togo, Gabon, and Morocco into supporting a coup attempt against Kérékou.

Denard was contracted to hire 90 “technicians” for the operation and given a budget of over $1 million ($5.6 million in 2025). On the night of 16 January 1977, this “Omega Force” landed at Cotonou, Benin’s capital; one detachment seized the airport, while another shelled the presidential palace.

Opération Crevette (Operation Shrimp) ground to a halt, however, due to two strange circumstances. The first occurred at the airport. A North Korean delegation was in town accompanied by a contingent of North Korean soldiers, who quickly counterattacked over the runway, pinning down Denard’s group.

Denard’s forward detachment, meanwhile, had been shelling an empty palace. President Kérékou was spending the night in a house nearby. When he heard firing, he rushed to the radio station, declaring that

“… a group of mercenaries in the pay of desperate international imperialism launched an armed attack at dawn this morning… Consequently, every activist of the Beninese Revolution… must consider themselves and behave like a soldier at the front.”

The coup attempt failed after just three hours. Denard retreated, abandoning documents identifying him and his men, down to the serial numbers on their weapons. A French court sentenced Denard, in absentia, to five years’ imprisonment. A Beninese judge gave him the death penalty.

Viceroy of the Comoros

With 1977 off to a bad start, Denard proved lucky once again. In February, Ahmed Abdallah Abderemane, former president of the Comoros, judged that the time was right to overthrow his successor, Ali Soilih. Soilih, a socialist, had come to power in August 1975 when he staged a coup against President Said Mohamed Jaffar, who himself had seized power from Abdallah. Denard had been involved in both coups, and found employment with Soilih. But Soilih, breaking ties with France, dismissed Denard.

Now, Soilih’s policies were wrecking the Comorian economy. Denard agreed to help Abdallah topple Soilih, in exchange for generous payment and a contract to rebuild the Comorian army. The mercenary agreed.

On the night of 13 May 1978, Denard and 80 men armed with hunting rifles landed by boat in Moroni, the capital. Determined not to repeat the Benin debacle, Denard had relied on a contact to make sure Soilih was in the presidential palace. He even took out a 2 million franc loan on a car dealership he owned in his hometown of Grayan to finance the expedition.

When his team reached the palace, Denard found the president in bed with two young girls. “So Mr. President,” he said, “this is the price one pays for failing to keep one’s word with one’s friends.” Soilih did not survive the night. The official explanation was that he was shot while trying to escape.

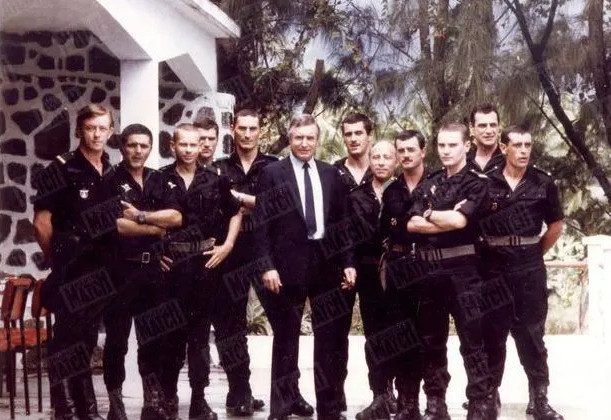

Denard’s men were soon rushing around the islands restoring order. The colonel himself became a popular figure: Comorians nicknamed him Bako (“wise one”), and hailed him as a savior of Islam from Soilih’s atheist regime. Taking a local wife, Denard converted to Islam under the name Saïd Mustapha M’hadjou and spent four months remaking the Comorian army and shoring up Abdallah’s new government.

Comorians considered Denard a hero. The rest of the world did not. The Organisation of African Unity, the United Nations, and countries willing to lend money to rebuild Comoros’ shattered finances refused to deal with Abdallah as long as “the wolf of the Indian Ocean” was in charge of his army. Knowing he couldn’t stay, Denard departed the islands once again in September.

The Colonel’s Downfall

Denard remained active in exile. The new Presidential Guard he’d established for Abdallah required money. During his time in Biafra, Denard had forged links with South Africa, and it was to this pariah state that he turned in 1979 for help. The South Africans agreed to fund Abdallah’s forces in return for a surveillance station on the islands and a chance to burnish their apartheid-damaged international standing.

The deal came just in time. In 1980, Denard’s patron, René Journiac, Foccart’s successor as Head of the African Department, died in a plane crash in Cameroon. The following year, François Mitterrand, a Socialist, would be elected President of France; the Socialists promised sweeping policy changes in Françafrique. During negotiations with South Africa, France quietly granted a last-minute blessing to return to Comoros.

For a decade, Denard was the uncrowned king of the island nation. He had his pick of business opportunities and authority to represent Comoros in financial aid missions abroad. France contributed over half of the national budget, which Denard couldn’t touch. The remainder, from South Africa, was under his complete control.

Denard’s power rested on the Presidential Guard (PG). This unit, made up of mercenaries and Comorians, functioned as a private militia for the colonel and a guarantee for Abdallah. During the 1980s, Denard and the PG foiled three coup attempts; the national army was largely sidelined.

Abdallah’s rule was vouchsafed by hired, lawless foreigners paid by the most hated country in Africa. Comoros’ worsening status in Africa, along with Denard’s souring reputation (several Comorians had been tortured to death by his men during the coup attempts), finally caused the delicate balance to crumble.

On the night of 26 November, Abdallah, “the father of independence,” was found shot dead in his office. Suspicion immediately fell on Bob Denard. “I am not the murderer of President Abdallah,” he countered. “Nor are any of the men under my command.” Disbelieving Comorians on the steps of the Grand Mosque shouted at the colonel, “‘Denard, assassin! PG nalawe! [get out]”

South Africa suspended its support; France sent warships. Denard claimed that Abdallah had ordered him to disband the dilapidated Comorian Armed Forces, and that a disgruntled army officer was the assassin; his critics pointed out that it was the PG that was unsustainable, and Denard who stood to gain if the president were out of the way.

The mercenary had nowhere to turn. Comoros now rejected him, South Africa could no longer afford the embarrassment of bankrolling him, and France risked international shame if Denard was allowed to remain in the islands. Leaving the country he’d called home for 15 years in the early hours of 15 December, 1989, Denard found refuge in South Africa; France refused to accept him.

Bob Denard’s Last Battle

For over 30 years and in every corner of Africa, Bob Denard had blazed a trail of destruction and controversy. He’d acquired six wives, friendships (and rivalries) with a score of dictators, and countless wounds. Denard was widely hated, but he cut a figure dashing enough that, in 1979, American director Clint Eastwood met with him to discuss making a movie based on his life. (Eastwood later soured on the idea of glorifying genuine violence).

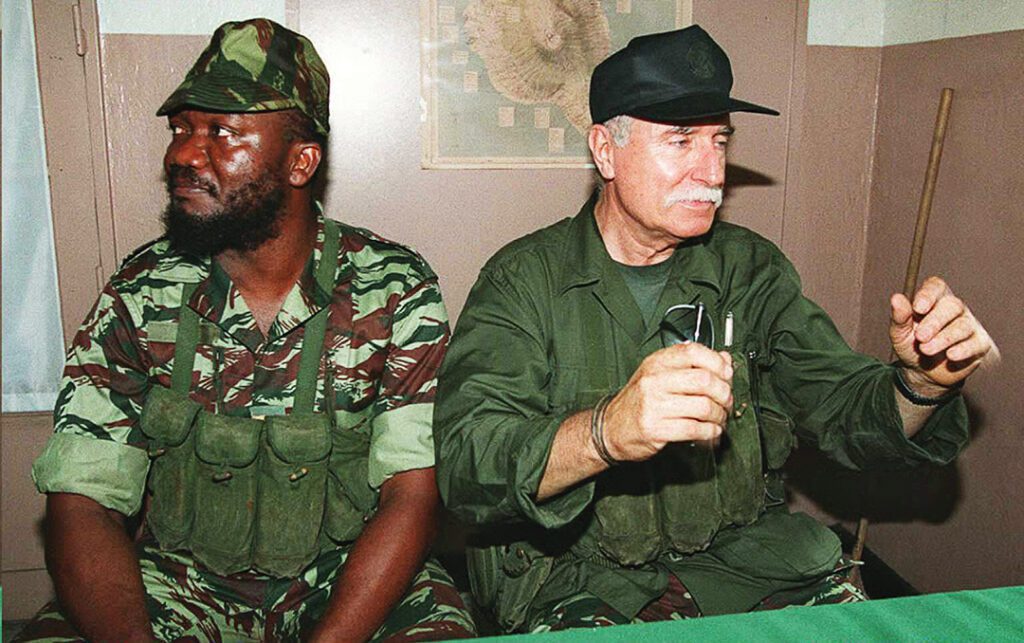

Even in exile, Denard still managed to sell his services to the Hutu-dominated Rwandan government during that country’s genocide. And finally, unable to resist one last grasp at personal glory, the old colonel took 30 men in inflatable boats to the Comoros on 27 September 1995. He overthrew Abdallah’s successor, Said Mohamed Djohar, but on 3 October, French troops arrived to finish Denard’s career at last. Even bolstered by nearly 300 Presidential Guards, the colonel could see that his time had ended. He surrendered without firing a shot.

Finally banished from his African fiefdom, Denard retired to France. Liable for three decades’ worth of criminal charges, the old colonel spent ten months in jail after his trial over the 1995 coup and was soon on trial again after his release. In June 2006, a sentence was finally handed down: five years’ imprisonment for “belonging to a gang who conspired to commit a crime.” A second sentence of four years came in June 2007. Denard, by then in his late 70s and suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, served no time.

Bob Denard died on 13 October 2007, unapologetic to the end. In 1993, Ahmed Abdallah’s sons’ death sentences (passed by a court loyal to Djohar) were commuted, allegedly thanks to President Mitterand and King Hassan II of Morocco. “Ask the people of the Comoros what they think of me now,” Denard said during a conversation with Weinberg. “Don’t you think they would like the Colonel back now?”

Podcast episodes about Bob Denard

Articles you may also like

The R1 – South African Bush Rifle

Reading time: 9 minutes

In the wake of the rise of the Soviet Union’s AK-47 and the USA’s litany of rifles during the Cold War, South Africa needed a modern automatic service rifle. After trialling several different guns, the South African government settled on the Belgian FN FAL battle rifle. As a result, the “Rifle R1” was born – the bush gun of Southern Africa.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.