Reading time: 6 minutes

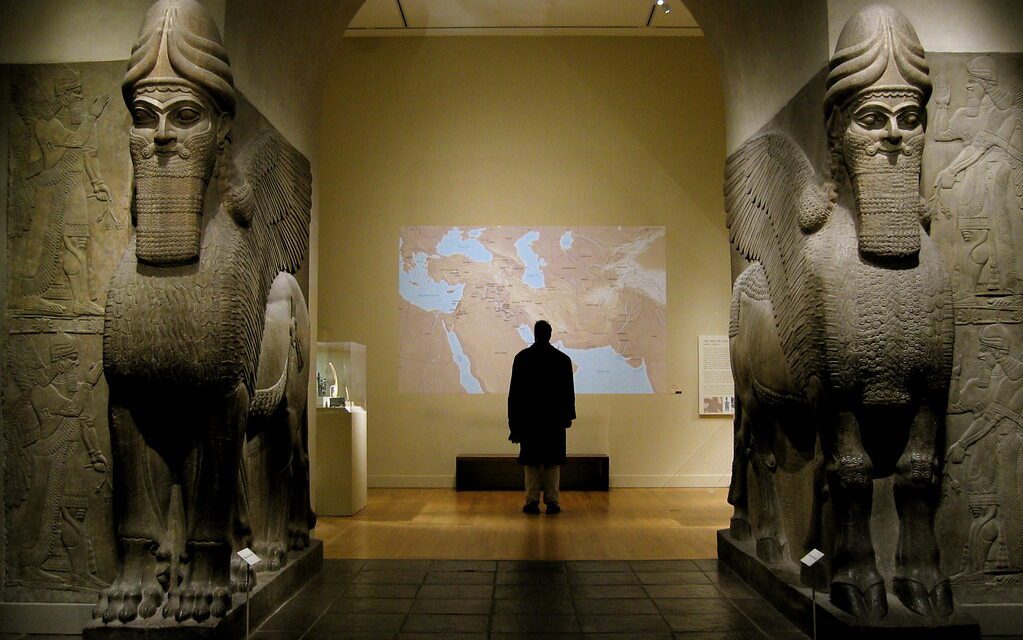

Mesopotamia, now located in the country of Iraq, has been home to some of Earth’s earliest civilizations and urban settlements, from the Sumerians to the Akkadians, as well as the centre of the Islamic world with the city of Baghdad under the Umayyad and Abbasid empires.

Yet the modern nation of Iraq is only just over 100 years old – a relatively new nation compared to many in the world.

How did Iraq, a home to ancient Empires turned battleground between bitter great powers, become the nation it is today?

By Mark McKenzie

From Ottoman Vilayets to British Mandate

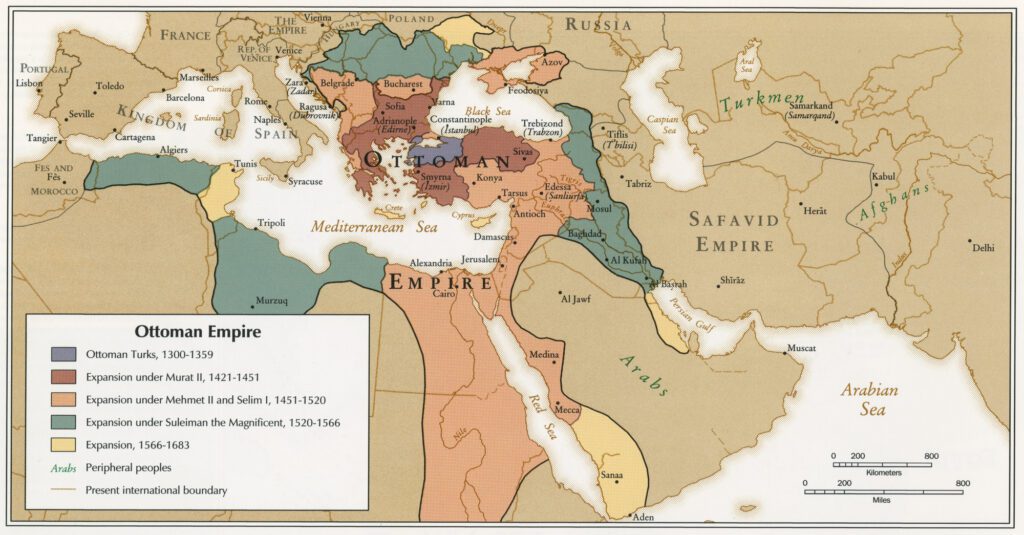

Following the fall of the older Islamic empires, the region of modern Iraq found itself a battleground between the Persian Safavids of Iran and the emerging Ottoman Empire, eventually coming under the more secure control of the Ottomans.

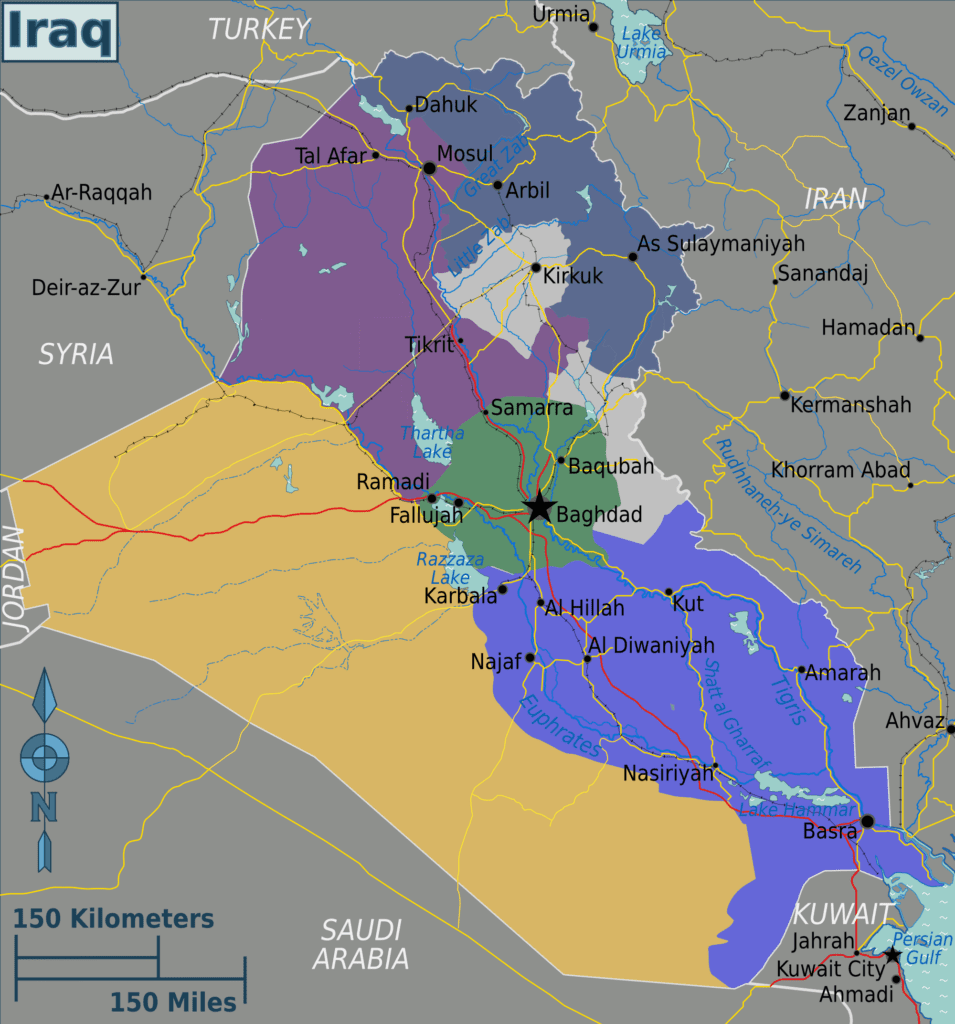

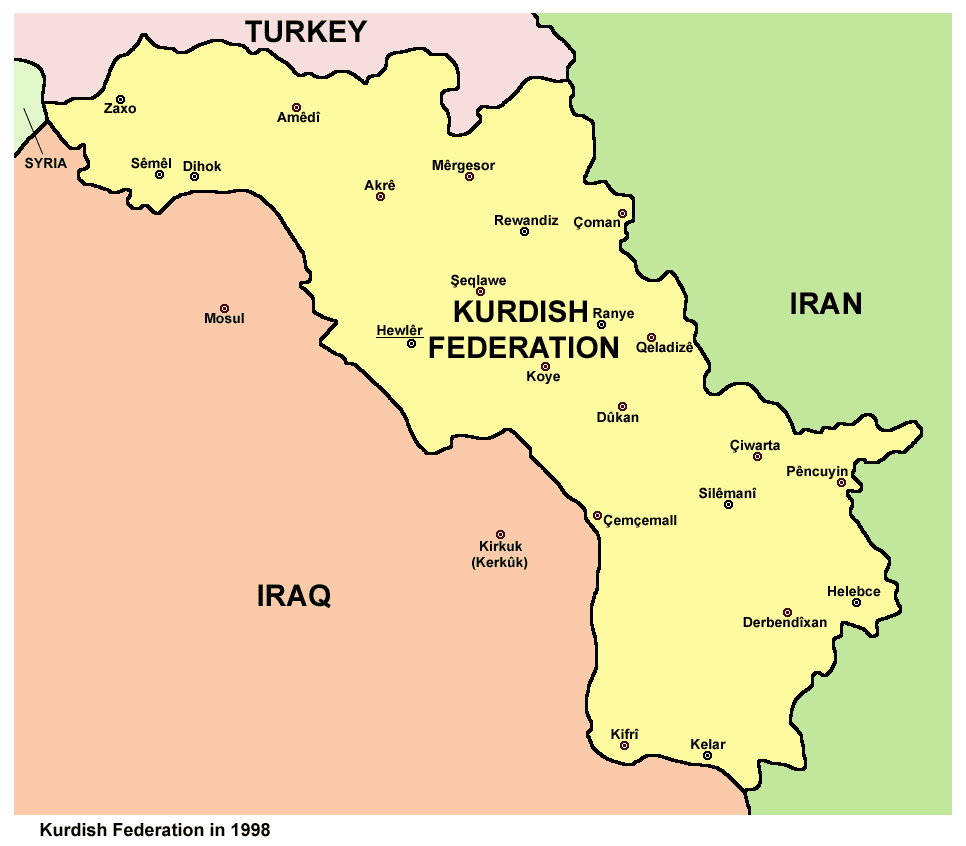

It is here that the region was administratively divided into the three vilayets (zones/regions) of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra. From many centuries of conflict, these vilayets were characterized by three distinct majority groups: the Kurds in Mosul, the Sunni majority in Baghdad, and a higher concentration of Shi’as in Basra.

Yet despite these divides, the three regions were consistently referred to by Ottoman elites as containing a single people — the Iraqi people.

Following reforms in the Ottoman Empire, administrative control of all three vilayets began to centralize under Baghdad at the centre, and despite some rebellious disturbances under Ottoman rule, the autonomy granted to the Iraqi region led to a long period of relative peace.

The Beginning of the End

Before the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I, the Allies had incited long-standing rebellious attitudes towards the Ottomans in the region. With the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, the British moved swiftly to take over the Basra and Baghdad vilayets and attempt to grant independence to the Kurdish region of Mosul.

Under the threat of the new Turkish state that emerged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, the British feared losing the Mosul vilayet and decided to incorporate it into the new mandate of Iraq at the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.

Thus, just as the new Turkish state was born of a homegrown nationalist drive, the new state of Iraq was forged from foreign fear and political strategy.

British Machinations: Crafting Iraq

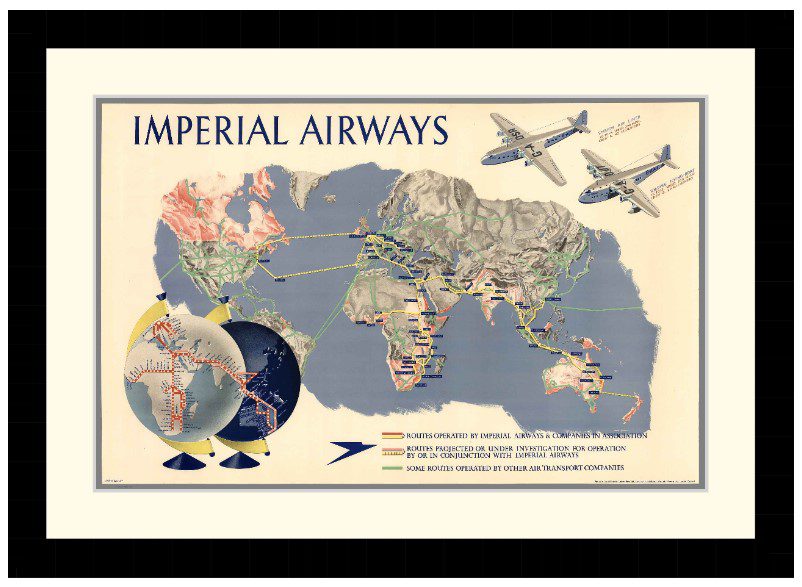

With the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the British sought to consolidate their influence in the region, particularly in territories rich in oil reserves.

At the top of the priority list lay securing access to Mesopotamian oilfields, and the threat of other powers, or worse – a new local power – gaining control over these fields propelled the British towards the creation of Iraq.

Sanctioned by the League of Nations in 1920, the British mandate of Iraq saw colonial policies aimed at fostering dependence and quelling dissent, with a minimal local armed force and hollow institutions.

The Formative Years: Political Turbulence

The Hashemite monarchy under King Faisal, installed by the British and imported from Syria, struggled to balance the challenge of forming a new nation for the interests of the people of Iraq without resisting British interests.

Despite Iraq’s independence being officially granted in 1932, the subsequent 1936 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty granted Britain a military presence and air bases in Iraq. While the Iraqi elite understood Britain’s exit would need to be slow if it were to happen at all, such treaties incited further anti-British sentiment, culminating in a series of uprisings and revolts.

With the government essentially formed by a British game of divide and conquer amongst the local tribes, Iraq’s political landscape during the first two decades of independence was characterised by a power struggle between competing factions vying for control.

Following the death of King Faisal and his successor taking power, political coups and assassinations gradually increased in frequency and severity. This turbulent period would set the precedent for what was to come.

Rise of the Baathists and Saddam Hussein

Founded in the 1940s with a resurgent pan-Arab nationalist agenda, the Baathists emerged as a distinct group within the government that campaigned for secularism, socialism, and Arab unity.

After rising to the rank of chief of police, Saddam Hussein led the Baathists to victory during the 17 July Revolution of 1968.

Having received assistance from the CIA, Saddam Hussein began his reign.

Paranoid from seeing previous leaders deposed and executed, Saddam Hussein focused on securing his own personal power, and his reign was marked with the brutal repression of all opposition.

While devastating for both countries, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), as well as the Gulf War (1990-1991), further solidified Saddam’s authoritarian rule.

The Iraq Wars: A Legacy of Conflict

The dawn of the 21st century would see Iraq enter two of its most pivotal conflicts.

The 1991 Gulf War, triggered by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, culminated in a swift and decisive military intervention by a US-led coalition. While the war resulted in the liberation of Kuwait, Saddam Hussein’s regime survived, albeit significantly weakened.

The 2003 Iraq War, this time driven largely by America’s blind crusade into the Middle East following 9/11, led to the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

At the time, the people of Iraq celebrated the end of the dictatorship. Yet as stability slipped from the region, many quietly began to miss the brutal peace of Saddam’s era.

The State of Modern Iraq: A Precarious Path

Modern Iraq continues to grapple with a troubled history and a violent present, with ISIS remaining a threat in the west of the country and the Kurdish fight for independence continuing in the north.

However, efforts toward national reconciliation, constitutional reform, and economic reconstruction offer a slither of optimism for Iraq’s future. The nation continues to be a battleground state for other regional players such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, yet hope persists.

Almost 60% of Iraqis identify first and foremost with their country over any other ethnic or religious identities, and each year brings news of the rebuilding of Iraqi institutions.

Nation-states take time and effort to form, and while Iraq may have a long road ahead to some semblance of stability, there remains cause for hope.

Podcasts about the history of Iraq

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.246

1. Who created Knight, Death and Devil in 1513?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The absurd irony of Putin’s invocation of Stalingrad

Reading time: 5 minutes

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s address in Volgograd on 2 February, in which he sought to draw moral parallels between the heroic Soviet defence of Stalingrad in World War II and the current Russian invasion of Ukraine, represents a new low for Kremlin propaganda.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.