Reading time: 7 minutes

When did South Korea become a democracy? A quick Google Search may give you many different answers – in 1948 the First Republic of Korea was established, moving on from direct US control that had commanded the country since the defeat of Japan.

Yet corruption was rife, the National Security Law restricted any groups who expressed support for North Korea (or opposed the state in general), and protests were met with violence.

So, not 1948. Well, the same Google search may instead point you to 1987, which saw a series of nationwide protests lead to significant political reform in the following years. Despite this, impeachments, protests and arrests of political leaders continued well into the 2010s. Not very democratic-sounding.

You may be wondering, what’s the real answer?

As with most things, the truth is complex. More recent events with the attempted, and failed, political coup attempt from then-sitting President Yoon Suk-yeol in 2024 shows just how ingrained South Korea’s recent history of political turbulence is.

This is the history of South Korea’s democratic struggle.

The Early Years – Democracy in the Context of National Security

As with many nations emerging from intense conflict, the military held significant sway in South Korea as it arose from the control and protection of the Americans, even more so than many other countries.

Like its northern counterpart, South Korea’s political situation, from its borders to its institutions, was a product of WW2.

Just a few years after the first Republic of Korea was created, the Korean War began.

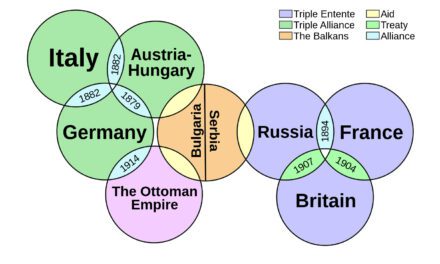

Not only this, the USA played a huge factor in early South Korean politics. Aside from holding governance over the territory between the defeat of Japan in 1945 and the birth of South Korea in 1948, the USA provided South Korea with over $127 billion in aid between 1946 and 2024.

In a policy of opposing Communist China as part of the Cold War, the USA supported the country as an ally, putting troops on the ground in the Korean War to assist South Korea alongside economic aid with the aim of countering communism.

This fact is key to understanding the National Security Law and aggressive stance towards possible communist elements in South Korea, and why in many cases ‘security’ took precedence over further democratic reforms.

Pre-Gwangju Authoritarianism: A Brief Overview

Due in large part to his time spent in the USA advocating for an independent Korea prior and during WW2, Syngman Rhee became South Korea’s first president following a political campaign focused on Korean unification – alongside convenient assassinations of most of the prominent moderate political leaders.

He then swiftly purged what remained of any opposition in the National Assembly.

Rapidly, Rhee gained complete control over most of the country’s political institutions – his authoritarian policies overshadowed only by the ongoing Korean War between 1950 and 1953.

Yet for all his authoritarian control, less than a decade later Rhee would be pressured out of power.

South Korean Student Power

In the March 1960 elections, the sitting government claimed a dubious 90% of the vote, despite receiving just 55% in the previous elections in 1956.

Huge protests erupted across the country, many of them student-led.

On April 19th, over 100,000 students nationwide took to the streets, meeting a harsh police response that caused over 100 civilian deaths. Following these deaths, calls for Rhee’s resignation grew from opposition-led to unanimously voted for by the National Assembly and supported by the USA.

Just over a week later, Rhee resigned and fled to Hawaii in exile.

The Post-Rhee Period

Following Rhee’s forced resignation in 1960, a brief democratic spring under the Second Republic would see South Korea develop into a parliamentary democracy, lasting just nine months.

What appeared to be progress towards stronger democratic institutions was quickly cut short by Park Chung-hee’s military coup in 1961. Based on a need to “restore order” and implement reforms, Park’s regime immediately dissolved the National Assembly, implemented Martial Law, and prioritised rapid industrialization over political freedoms.

Only under immense pressure from the USA did Park reintroduce elections in 1963, in which Park narrowly defeated the opposition to form South Korea’s Third Republic.

Elections would continue every four years, riddled with accusations of fraud, protests, and political manoeuvring such as amending the constitution to allow Park to run for more than two terms, before once again doing away with popular elections in 1972.

In 1979, following increasing domestic tension, Park was assassinated by the then-director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency. What may not come as a surprise, the vacuum left by Park’s death was quickly filled by Chun Doo-hwan, another military strongman.

The Gwangju Uprising

In May 1980, martial law was implemented as Chun again amended the constitution.

Following a long tradition of student-led demonstrations, the city of Gwangju erupted in protest against Chun’s martial law decree. What began as student demonstrations quickly evolved into a city-wide rebellion.

Citizens quickly broke into police stations and armouries, arming themselves and facing off against 18,000 riot police and 3,000 paratroopers, and on May 21st the government retreated, with the protests proclaiming the city liberated.

Just six days later, Chun’s government forced re-entered the city with tanks, armoured carriers and helicopters, crushing the uprising in two hours, killing anywhere between 200 and 2,000 civilians.

Failed Suppression

The government’s attempt to suppress the Gwangju Uprising through force ultimately backfired. While short-lived, the Gwangju uprising demonstrated a clear resistance to authoritarianism in South Korea.

Following the suppression, an underground network of students, workers, and religious groups formed, maintaining pressure on the regime throughout the 1980s. This push was further supported by the global community’s push towards forming democratic nations.

The June Democratic Struggle of 1987

The death of student activist Park Jong-chul under police torture in January 1987 became the catalyst for further nationwide protests. When another student, Lee Han-yeol, was fatally wounded by tear gas during demonstrations, public outrage reached a boiling point.

The June Democratic Struggle of 1987 saw millions of South Koreans take to the streets, forcing the government to accept democratic reforms. The ‘June 29 Declaration’ promised direct presidential elections and other democratic measures, marking a significant victory for the pro-democracy movement.

While South Korea’s democracy was not secured in a year, this struggle, built upon the sacrifice and protest of many before it, saw the implementation of South Korea’s modern democratic system.

A Long Road Ahead

Recent events have shown that South Korea’s democratic institutions are not as secure as many in the west may have assumed. While Korea as a whole has a long history stretching back well into the 2nd Century BCE, the modern country of South Korea is still young in the context of the world stage, as are its institutions.

Actions such as martial law can often be interpreted by everyone, historian or not, as running counter to democracy.

However, all democratic countries face constant threats to their democratic institutions, from internal degradation to external sabotage.

The truth is, no country has ‘finished’ its journey toward democratisation; like a home, democracy is a shelter that must be constantly maintained, developed, and sometimes expanded upon to serve its purpose.

Like any other democratic country, South Korea is still on its democratic journey, and its people have so far shown their determination to stay on this path.

Podcast episodes about South Korean Democracy

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 41

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. If you would like an invite to future history quizzes please enter your details below. Subscribe * indicates required Email Address * First Name Last Name History Guild Weekly History Quiz Weekly New History Articles and News Monthly History Guild Update Please leave […]

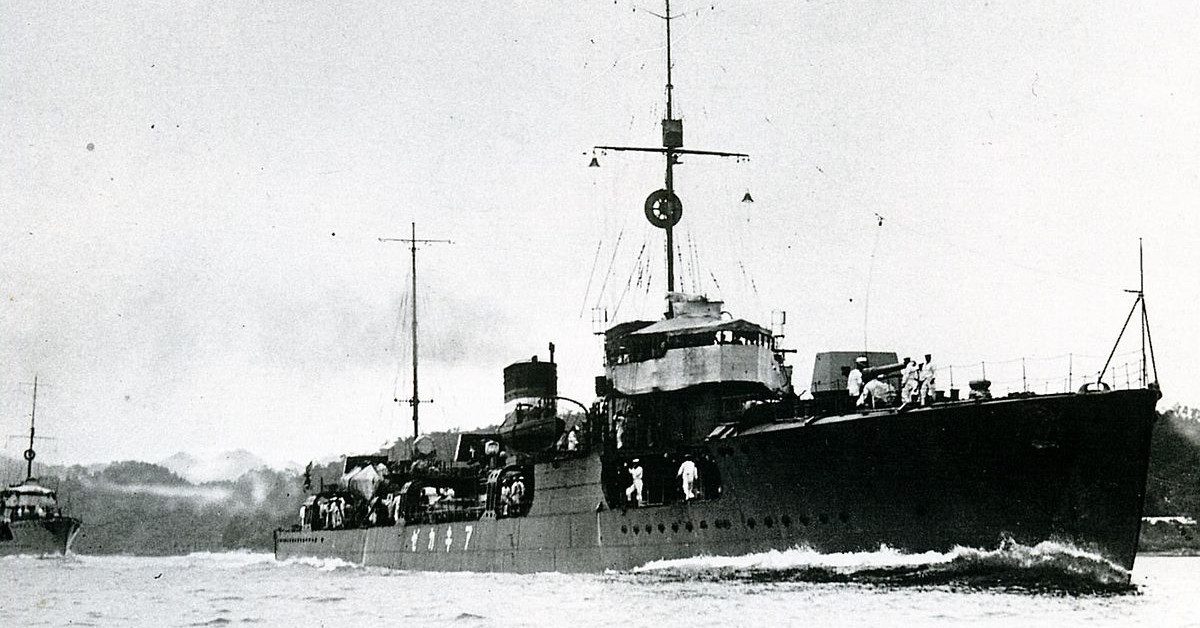

The Akikaze Massacre: the Japanese Navy’s Mass Murder in the Solomon Sea

Reading time: 12 minutes

When the Pacific War began in 1941, Japanese military planners had long recognised that they could not hope to win a protracted war against the United States, its likeliest and likely deadliest opponent in the Pacific. Instead, they pinned their hopes on a swift, devastating series of campaigns to seize strategic points.

General History Quiz 147

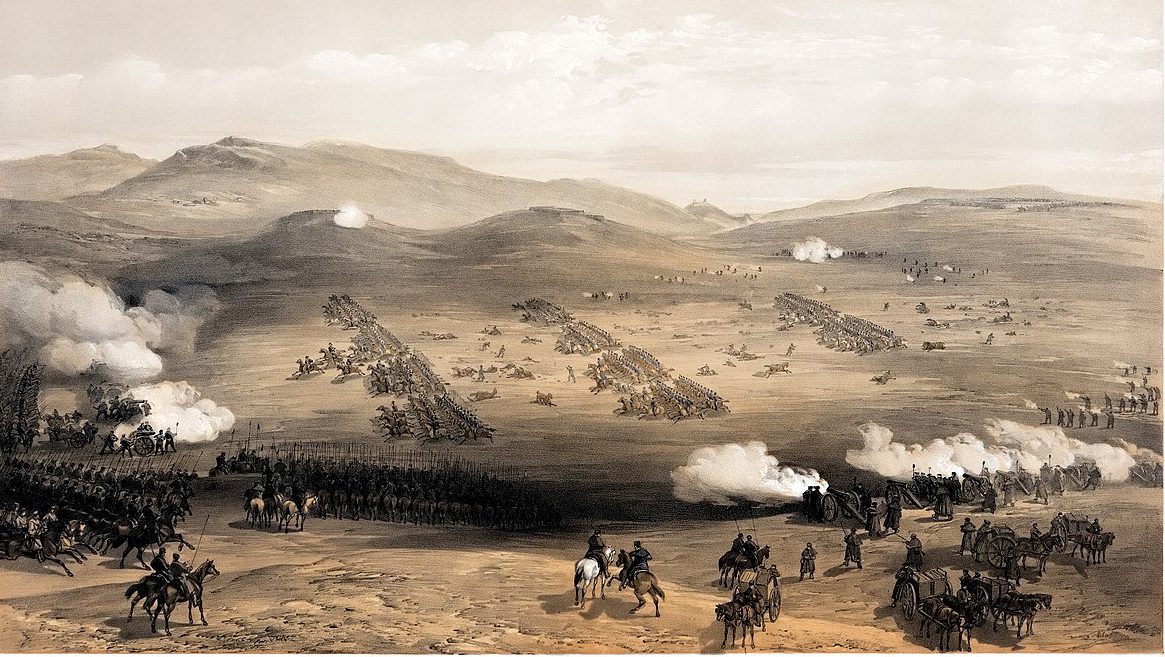

1. When did the famous Charge of the Light Brigade occur?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.