Reading time: 11 minutes

To the Axis Powers, the Australian flotilla that fought in the Mediterranean during the Second World War appeared to be no threat. Anyone looking at the old, small and slow destroyer group would think the same. Soon, however, the Axis and the rest of the world would learn just how formidable it was. The ‘Scrap Iron Flotilla’ and those who manned it proved just how much grit, determination and valour can achieve.

By Madison Moulton

The Scrap Iron Flotilla

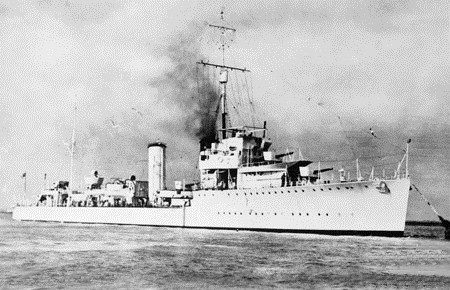

The flotilla of destroyers was made up of five ships: Stuart, Voyager, Vampire, Vendetta, and Waterhen. Completed in 1918, these ships were designed to the standards of the First World War. Given the massive advancements in military technology by the late 1930s, the flotilla was considered obsolete by the beginning of the Second World War.

Australia acquired the vintage destroyers, readying them when war broke out in 1939. Just three months in, they were sent to Singapore to protect the country from a potential Japanese attack.

By 1940, the situation in the Middle East and along the Mediterranean had grown more dangerous. Before Australia’s decisive victory at Bardia, Libya, this flotilla had already begun to make its mark. The flotilla arrived in Malta in January 1940.

When the Axis first discovered that the ships were in the Mediterranean they saw it as a chance to win a propaganda victory. Compared to the modern, fast, and powerful ships of the German and Italian navies, the Australian destroyers seemed to be outclassed. So Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Propaganda Minister, thought he was being intimidating when he named it the “Scrap Iron Flotilla”.

Taking to nickname, the Australians renamed the flotilla as such. The Scrap Iron Flotilla would go on to prove that even though the ships looked insignificant, they could still do more than their part to help win the war.

The Men Behind the Flotilla

A group of warships is only as formidable as the sailors manning them. Hector Waller, Fredrick Offord, and Ean McDonald were just three of the hundreds of young Australians that helped make a name for the Scrap Iron Flotilla.

Ean McDonald

Ean was born in Melbourne and grew up during the Great Depression, working in a small factory after he left school. McDonald’s love for sailing began early on. Before he joined the Sea Scouts, he would build canoes out of scrap corrugated iron and sail them on a local lake. Fighting at sea ran in the family, both his grandfather and father were part of the Royal Naval and fought during World War I. McDonald was aware of the hostile situation brewing in Europe and grew more and more concerned. The year before World War II began, he joined the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) as a signalman.

One of the tasks of a signalman was to know a good selection of phrases from the Bible, in order to use them as impromptu code. He described how it worked “so that lets say that your captain said to you “Oh signalmen look I’d like to send this signal to HMAS Voyager, I’d like him to come over and have dinner with me, can you think of a appropriate signal?” And so you’d say, “Oh yes Sir. I think that Matthew 10 Verse 2 might be a good one and he’d say what’s that?” And say “Well that’s says that he called upon his disciples and ask them to come sup with him”. And he’ll say, “Oh yeah that’s fine.” So the signal would go out, Matthew 10, 2 and the signalmen at the other end would have to open the bible and say, “Well sir the captain of so and so said to you the disciples are invited to come and sup with him”

Ean left Australia on the cruiser HMAS Sydney, famous for sinking an Italian cruiser at the Battle of Cape Spada. Early in the war HMAS Sydney was asked “have you got any spare signalmen?” And they said, “Well McDonald’s no bloody good send him!” So he was transferred to HMAS Stuart, commanded by Hec Waller, who he described as a wonderful man.

Ean took part in the bombardment of Bardia, made 25 runs as the Tobruk Ferry, which kept the besieged Australian 9th Division supplied and was bombed more times than he can remember. He was part of the Battle of Cape Matapan, where HMAS Stuart was damaged. He and Hec Waller transferred to HMAS Waterhen, which was sunk a short time later by German JU-87 Stuka dive bombers. He survived this, and the war, continuing to serve in the reserves for years afterwards.

Fredrick Offord

Fredrick Offord was a member of a navy family, much like Ean McDonald. His father had been a Merchant Mariner during the Great War and his brother was in the navy. Fredrick was born in Port Melbourne, attending Nott St Primary School. During the great depression, Offord’s family was amongst the millions who were terribly affected, moving from house to house because they couldn’t afford the rent. As soon as he turned 18 he joined the navy.

He joined HMAS Voyager as a stoker. This meant that he spent his time in the boiler room, ensuring it was delivering the power needed to keep the ships speed up and dodge the enemy shells and bombs. Working in the boiler room during combat took a particular type of courage, as the sailors there had no idea what was happening outside. They would get no warning of a hit on their ship, just the inrush of tonnes of water.

Fredrick was also part of the Tobruk Ferry, as well as evacuating British, Australian and New Zealand troops from Greece.

Hector Waller

Born and attending primary school in Benalla, Vic, at 13, Hector MacDonald Laws Waller joined the Royal Australian Naval College (RANC) as a cadet midship. Throughout his time at the Naval College, he climbed ranks. He was sent to Britain to serve in the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, though he didn’t see combat. After several years of training Waller was given his first command at sea on HMS Brazen. This ship was tasked with monitoring the Spanish Civil War. When the Second World War broke out, Waller was appointed captain of the HMAS Stuart, the lead destroyer of the Scrap Iron Flotilla.

Hec Waller was highly respected both by the officers and men he lead as well as the senior echelons of the Navy. After leading the Scrap Iron Flotilla he was promoted to command HMAS Perth. This was sunk in the Battle of the Sunda Strait in March 1942. Hec Waller went down with his ship.

The Warhorses of the Mediterranean

Malta and Beyond

During its time in Singapore, the Scrap Iron Flotilla and its men became acquainted with submarines and anti-submarine tactics. This critical training allowed them to achieve their successes in Malta.

They saw their first major action in June 1940, just after Italy officially entered the war. Almost immediately, Malta’s shipyard was under attack by Italian bombers. The destroyers were set to work immediately. Italian submarines had strategically placed mines around Malta, in anticipation of the Royal Navy steaming out to engage the Italians. The minefields remained unnoticed until HMAS Stuart, captained by Hector Waller, saw the mines as they sailed past. The old destroyer narrowly escaped destruction and all 5 began hunting the submarines.

This old flotilla proved its strength and ability quickly. Italy had only been in the war for 9 days and already they’d lost two submarines to the Scrap Iron Flotilla. Waller was more than just a captain on HMAS Stuart. He took his turn in shooting floating mines during the patrols. Their success in Malta was just the beginning.

Following their success at Malta, the Scrap Iron Flotilla assisted the Allied forces all around the Mediterranean. HMAS Stuart shelled Bardia, a small fortified town in Libya under Italian Control.

Despite the old technology and the jokes made about the Scrap Iron Flotilla, they quickly became a force to be reckoned with. Members of the flotilla were very proud to be a part of this force.

“We kept it going with string and wire and whatever so they said. Yeah. Yes, I’m very proud of the Scrap Iron Flotilla”.

Fredrick Offord, Stoker, HMAS Voyager

Battle of Cape Matapan

The tone of the war changed in the Mediterranean with the Battle of Cape Matapan in March 1941, one of the most important naval battles of the war.

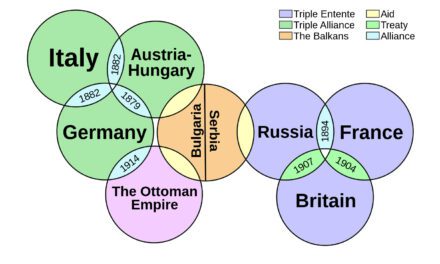

In the weeks leading up the battle, analysts cracked the Italian Naval code, finding out that they planned to attack Allied merchant convoys on their way to Greece. There had been a critical miscommunication between the Axis over and above that which aided in the Allies decisive victory. The Italians were informed that their opposing forces in the Mediterranean were made up of a single functional battleship, with no aircraft carriers. In reality, the Royal Navy had three battleships and a fully functioning aircraft carrier. Accompanying the main fleet were members of the Scrap Iron Flotilla.

First Shots Fired

Upon hearing of the approaching Italian forces, several destroyers left Alexandria on March 27th. Despite hearing that they lost the element of surprise, the Italians forged ahead with their plans. 28th of March saw the first shots of the battle fired. Just after 8am, the Italians began firing on a British Squadron moving toward the southeast. Three Italian cruisers continued firing for almost an hour. Despite this, the Italians scored very few significant hits. The Allied ships changed course and closed the range to the Italian fleet. After a few minor hits from Italian forces, the Allies moved further away.

Air Attacks

From there, the Allies began attacking from the skies, sending torpedo bombers from the HMS Formidable. They scored a hit on the Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto, damaging one of her propellers. The Italian main fleet began to withdraw towards Taranto.

Fighting at Night

The Allied forces detected the Italian squadron on radar shortly after 22:00, and were able to close without being detected. The Italian ships had no radar and could not detect British ships if they couldn’t see them. The Italians had not trained extensively for night actions and their main gun batteries were not prepared for action.

The battleships Barham, Valiant, and Warspite were able to close to 3,500 m – point blank range for battleship guns – at which point their searchlights were turned on and they opened fire. One of those searchlights was directed by Midshipman Prince Philip, aboard Valiant.

After The Battle

This massive Italian defeat proved the inadequacy of their training, especially for night battles. This lead to the Italian surface ships mostly avoiding battle. The German and Italian air forces however kept up a steady pressure on the Allied ships.

The Scrap Iron Flotilla were the backbone of the Tobruk Ferry service, which kept the besieged garrison at Tobruk supplied and able to fight. The Germans and Italians knew they had to keep doing this, and were waiting for them with dive bombers every trip.

The odds were stacked against the Scrap Iron Flotilla once again. But they continued to prove their worth, successfully evacuating over 40,000 men and bringing in over 30,000 reinforcements. During the eight-month siege, they brought in thousands of tonnes of stores.

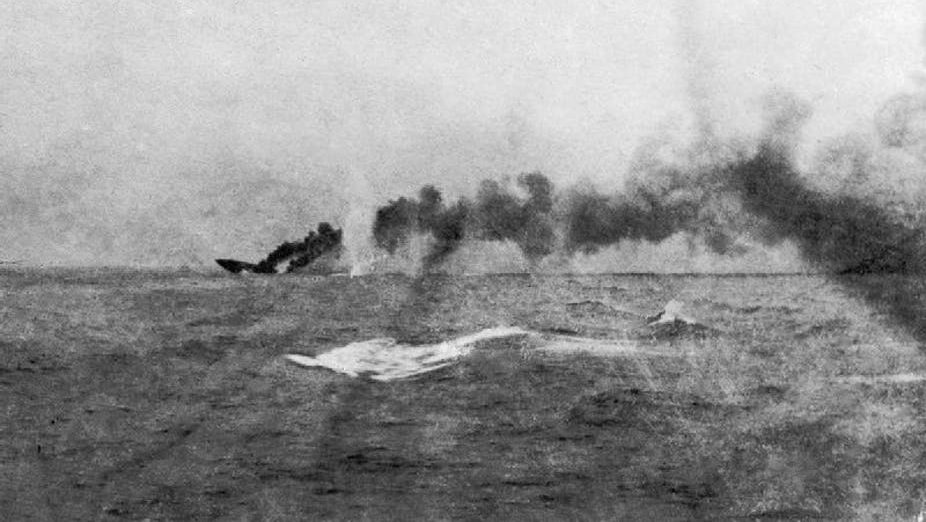

Many ships were lost during the Tobruk Ferry, including HMAS Waterhen. HMAS Waterhen was the first Australian vessel lost during the Second World War, and after it’s loss the old and battered Scrap Iron Flotilla sailed back to Australia. They were refitted, before seeing action against the Japanese.

The Scrap Iron Flotilla were true underdogs in the Mediterranean theatre. Their age made them seem obsolete, especially when compared to the Italian and German naval and air forces. Despite this, they more than proved their worth and strength.

Podcast episodes that discuss this topic

This project commemorating the service by Victorians in the Mediterranean theatre of WW2 was supported by the Victorian Government and the Victorian Veterans Council. Sign up to the newsletter at the bottom of the page to be notified when the next article in this project is released.

Articles you may also like

The Battle of Cape Spada: The Australian Navy Proves Its Mettle

Reading time: 9 minutes

The Battle of Cape Spada was a short, violent encounter on the 19th of July, 1940 where the cruiser HMAS Sydney of the Royal Australian Navy sank one Italian cruiser and severely damaged another off the coast of Crete. In this article, we go over the events of that day, as well as what life was like for the crew of the ship.

Battle of 42nd Street – Anzacs Proving Germany Could be Beaten

Morale can make all the difference on the battlefield. On the 27th May 1941, with the Greek island of Crete close to loss and the Allies in full retreat, a 12 minute moment of madness by Australian and New Zealand troops proved that aggression and bravery could overcome Germany’s elite troops. By Richard Shrubb. Background […]