Reading time: 7 minutes

To combat the prodigious run scoring of Australian batting legend Don Bradman, the captain of the visiting English cricket team, Douglas Jardine, instructed his four fast bowlers to bowl at the man not the wicket in the summer of 1932-33.

Australian batsmen had a choice – get hit or get out. The English team returned home with the Ashes.

By Marion Stell, University of Queensland

Australian spectators, the press, former players and the general public were incensed. Nothing else was spoken of at work, on public transport or in the home. The controversy raged in the press and reached parliament and the pulpit.

The “Bodyline” series caused a deep rift in relations between Australia and England and seriously threatened the bonds of the empire during the Great Depression.

It is an enduring story of sport, a compelling mix of cricket, politics, skulduggery, bravado, high passion and danger. Over time, numerous books, a mini-series and films have fleshed out the actors, delved into their behind-the-scenes motivations and fears, and examined the repercussions.

But it is told as a men-only story. The major actors all share the same gender – from Bradman, Woodfull and Oldfield to Jardine and Larwood, from the members of the Marylebone Cricket Club to those of the Australian Cricket Board, from past players to the gentlemen of the press.

However, cricket has never been the sole preserve of male players and spectators. It’s a sport that speaks to and attracts all genders.

The story of a young Don Bradman hitting a golf ball with a wooden stump against the base of the household water tank is part of Australian folklore. Less well known is the fact that his mother, Emily Whatman, regularly bowled her left-armers to him every afternoon after school.

The long history of women in cricket

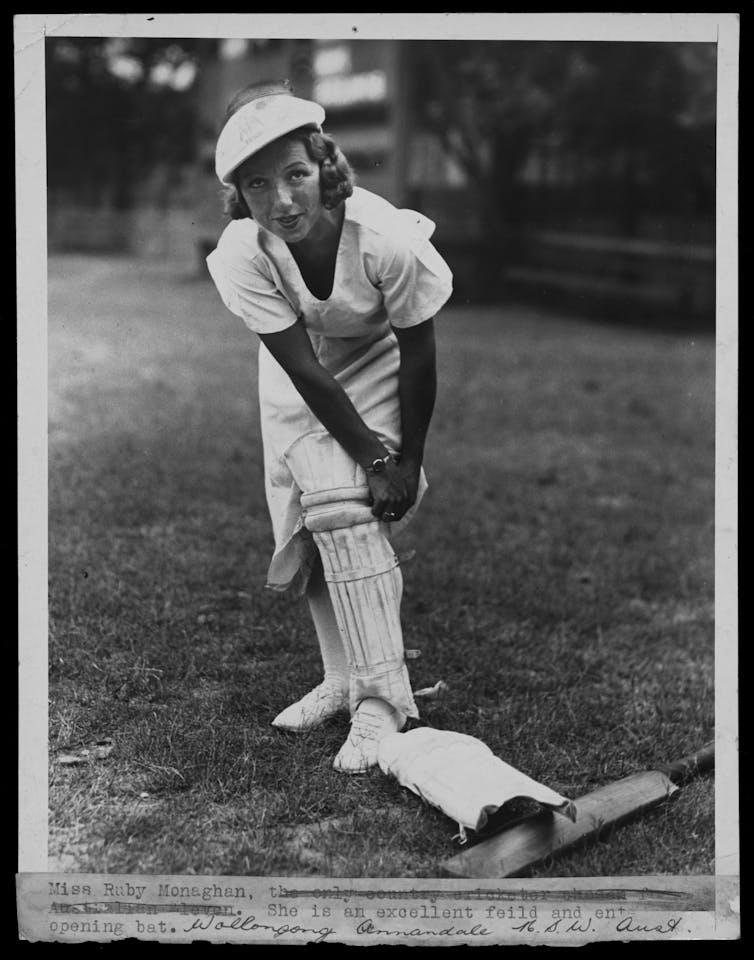

Some of the earliest records of women playing cricket date back to 1745 in England and 1855 in Australia. Emily Whatman was part of a strong cohort of enthusiastic players from the 1890s.

The snowballing interest in playing cricket had led women to form their own national cricket associations in England by 1926 and in Australia by 1931.

The English women set themselves on what could be described as a separatist course. Faced with hostility from the male establishment and the English press, the players ‒ led by leisured and upper-class women ‒ created cricket grounds on their own estates, formed their own competitions, prohibited male umpires, refused to play in mixed matches and even published their own subscription magazine, Women’s Cricket, to control the messages about their sport.

However, such was not the case in Australia where the growth of cricket owed more to a co-operative spirit between the sexes. The game was open to women and girls from all classes. Many young women learnt their cricket skills in street games alongside boys and men.

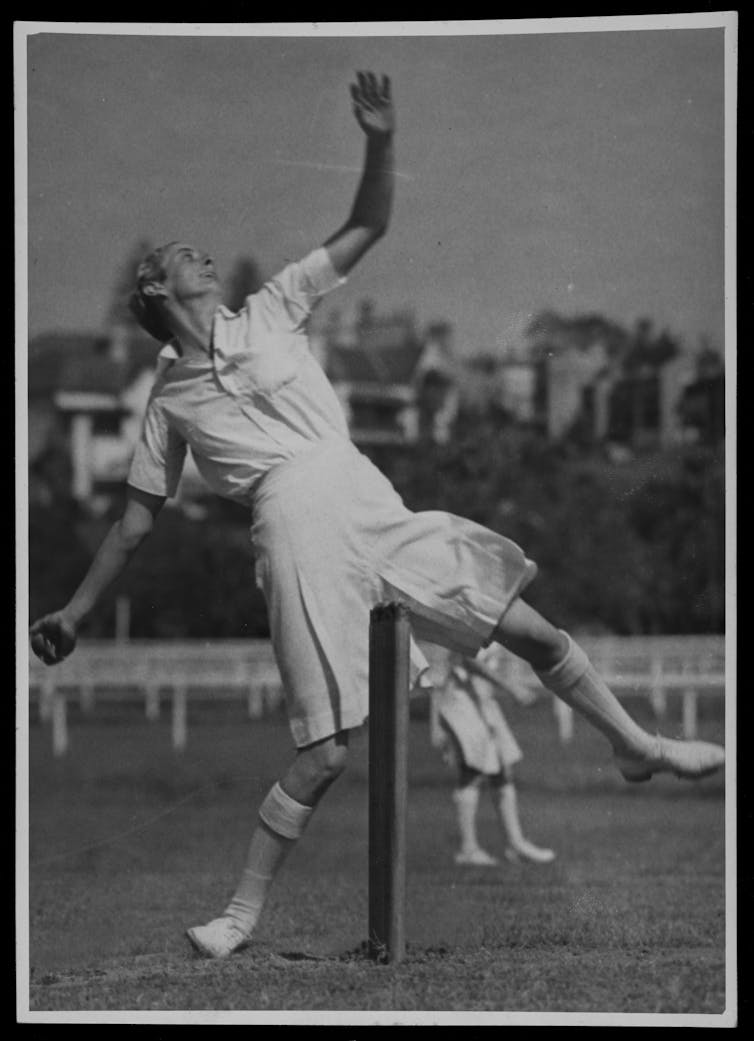

Two Australian players, outstanding leg-spin bowler Peggy Antonio and left-arm seamer Anne Palmer, recalled how they honed their skills devising ways to get the local boys out. They knew the boys could play fast bowling all day.

Women in New South Wales established their own indoor practice nets in 1931, open to all comers. Many women and girls also attended the coaching school run by Fred Griffiths near Central Station in Sydney where they trained and played alongside men and boys. Emerging medium-fast bowler Amy Hudson recalled her enjoyment at bowling to brilliant batsman and local Balmain boy Archie Jackson.

Women’s club cricket matches in Melbourne, especially those between Collingwood and Clarendon, attracted thousands of male spectators, many barracking for their favourite “heroines” on the field and betting on the outcomes of games.

Australian captain Margaret Peden had helped found the Sydney University women’s team in 1927. Her father, Sir John Peden, was professor of law at the university as well as president of the NSW Legislative Council. The Peden name was respected and doors opened. Mixed matches between students and staff at the university attracted many professors away from their desks and were supported by former Test cricketers Charlie Macartney and author and journalist Dr Eric Barbour.

Awareness of women playing cricket spread rapidly. Keith Murdoch at the Melbourne Herald employed all-round sportswoman, cricketer and journalist Pat Jarrett to write a weekly column on women and sport. It proved so popular that when a new magazine, the Australian Women’s Weekly, was launched in June 1933 it included a double-page spread on sport by journalist and cricketer Ruth Preddey. Other newspapers followed suit.

‘A mighty success’

Jarrett shared with her readers the opinions of Australia’s top sportswomen on the Bodyline series. Women spectators, present in large numbers at the men’s games, wrote letters to the editor of major newspapers bemoaning the actions of the English bowlers. Women players in South Australia banned the use of bodyline tactics in their own games. Women’s voices and opinions were heard and reported everywhere.

When the much-anticipated English women’s team led by captain and lawyer Betty Archdale arrived in Australia for the inaugural Test series between the two countries in the summer of 1934, the opportunity to restore the game of cricket in the eyes of the public was uppermost in the minds of many, not least the persistent Australian press. Reporters bombarded the captain and her manager with questions on Bodyline.

Also touring in 1934 was the Duke of Gloucester, ostensibly to celebrate Victoria’s state centenary, but with speculation that it was partly a goodwill tour to restore diplomatic relations between Australia and Great Britain. The press was forbidden from asking the royal visitor about Bodyline.

The strong links and enduring bonds between Australian and English women were evident during their cricket tour – from personal connections between players and officials to those established between international women’s organisations.

The English women played matches in Western Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and Canberra. By the end of the series the press, the players, the spectators, the public and every local mayor declared the tour a mighty success.

Many of the Australian players compiled bumper scrapbooks of their cricketing years and collected evocative souvenirs reflecting the intersections between all the great cricketers from the 1930s, both male and female. It was an era of mutual respect between the country’s elite cricketers.

Women players enjoyed the long-standing support of many male champions from cricket, especially Charlie Macartney, Bill O’Reilly, Arthur Mailey, Stan McCabe and Alan Kippax.

Many saw women as equal partners in cricket, with a clear role in delegating the Bodyline era to history.

How women saved cricket

To write about the 1930s and Bodyline and not write about women playing the same game in the same era misses half the story.

The women transformed the damaged reputation of cricket through personal connections, hospitality and commonalities of purpose. Not only did the tour go a long way towards mending the relations between the two countries, but it smoothed the way for the game of cricket to once again be regarded as embodying fair play and sportsmanship.

On the field, the women won over the crowds and the press with their high standard of play and their deep knowledge of the game. Match after match they demonstrated that elite, competitive cricket could still be played in a sporting and civilised fashion.

Off the field, they had charmed their way around Australia. Planning began immediately for a return series in England in 1937.

After the Bodyline summer of 1932-33, the cricket world had been tilted off its axis. Cricket’s reputation was well and truly tarnished. These teams of women were the good news story that fixed it.

If one of the biggest controversies in Australia sport can be written about for nearly a hundred years without reference to the vital intersections between the men’s and women’s games and the crucial role of women, it makes me question: what else are we missing? What other sporting narratives deserve scrutiny and revisiting?

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about the history of the Bodyline series

Articles you may also like

The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 7 – Audiobook

THE GREAT EVENTS BY FAMOUS HISTORIANS, VOLUME 7 – AUDIOBOOK By Charles F. Horne (1870 – 1942),Rossiter Johnson (1840 – 1931) A comprehensive and readable account of the world’s history, emphasizing the more important events, and presenting these as complete narratives in the master-words of the most eminent historians. This is volume 7 of 22, covering from […]

General History Quiz 181

1. Which country manufactured the largest battleships ever made?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Why we should remember the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 has become the touchstone for the Australian-American strategic relationship. The 75th anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on why this engagement, in which for the first time the opposing fleets did not sight one another, still resonates. By Peter Jones During the six months after the […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.