Reading time: 7 minutes

Most people have heard Jonestown Massacre in 1978, when 918 members of the Peoples Temple committed suicide by drinking the proverbial Kool-Aid under instructions of the leader of their cult, Jim Jones. How did Jones get this kind of influence over his followers, though, and why would they even consider suicide?

By Fergus O’Sullivan

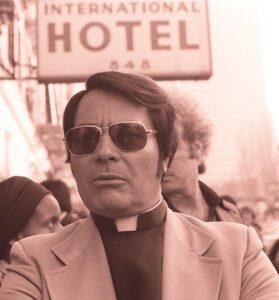

Like many of the world’s tragedies, the story of the Peoples Temple and Jim Jones starts with good intentions. Born in 1931 in Indiana, Jones started the first Peoples Temple in Indianapolis in 1955. Jones seemed to have some kind of utopian vision in mind, with many collectivist ideas for the community he had founded, where people would share what they had with others.

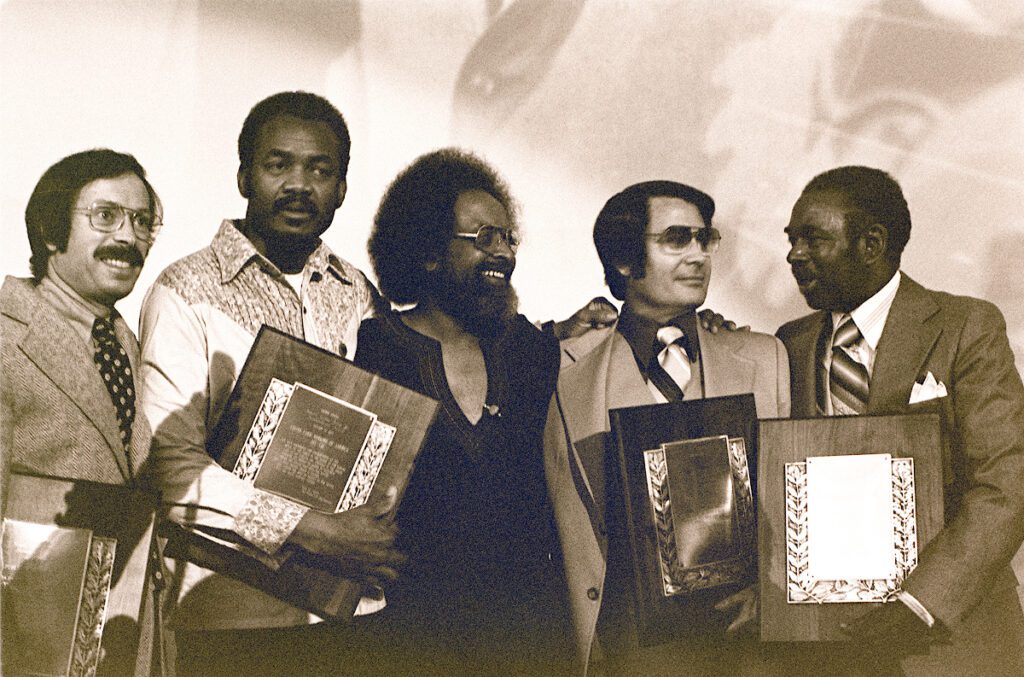

His vision included racial integration, a pretty big deal for the America of the 50s and 60s, and as a result many of his flock were African American. When the church moved to California in the early 60s, the reputation for being tolerant and helpful only increased. The Peoples Temple helped many good causes, many of which focused on the troubled inner cities, like a free medical clinic and facilities for the homeless.

Understandably, this drew many new followers who wanted to help Jones and the church create a better world. However, as his flock grew, so did Jones’ ego and with it the darker side of Jones’ personality. For example, the reason the Temple moved to Northern California in the first place was because Jones had read that it would be safe in case of nuclear war.

The Trouble Starts

As the 60s turned into the 70s, this paranoia entered into his daily life. He saw plots everywhere. There were reports of members of the church being beaten for insubordination. It was also becoming increasingly clear that the Peoples Temple idea of sharing involved members being pressured to give up everything they had to the church.

As seemingly happens with all cults run by a single powerful man, this power quickly went to his head. Jones started staging healings in which he claimed to cure people’s cancer—he didn’t, the people died—and he, of course started philandering his way through his flock, having sex with many of the men and women that looked to him for spiritual teaching.

With the attention on Peoples Temple becoming increasingly negative, Jones drew up a plan where the church would flee the United States, away from the federal government and its pesky interest in the rule of law. Jones settled on a site in the hinterlands of Guyana, a small exclave nestled between Brazil, Venezuela and Suriname where he and his followers could create a utopia.

Jonestown

The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project — called Jonestown by, well, everybody — was initially settled by a small vanguard of believers who struggled to make anything grow or build much in the jungle. Most of the pictures we have of it were taken by the FBI after the massacre, and the town looks downright terrible, with houses falling apart.

What made things worse is that when Jones came, he brought about 900 people with him, overwhelming what little infrastructure there was. People went hungry, were crammed into inadequate housing and discontent grew. Jones’ idea of motivation was to hold sermons day and night, broadcasting them over loudspeakers that covered the entire compound. Keeping his followers awake with his rants did little to bolster spirits.

The grumbling only further fuelled Jones’ paranoia, and the already unhinged behaviour grew even worse. For example, while he had for years surrounded himself with bodyguards, he now turned them into an improvised soldiery and armed them with rifles and crossbows.

Jonestown, which was supposed to be a utopia where all would share and share alike, quickly became a Soviet-style gulag, and people wanted out. Reports had been coming back to the States about what was going on in Guyana, but the flashpoint was the custody battle over a six-year old son of a married couple who were members of the church.

Jones had claimed custody over the child, claiming it was his — it could have been — and the parents had acquiesced, signing custody over the child to Jones. The couple left the church a little after, but Jones had taken their child with him to Guyana. A lengthy court battle ensued, which drew the eye of investigators to what was happening in the Latin American jungle.

A Congressional Visit

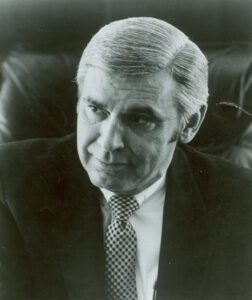

One of the people who grew interested was Leo Ryan, a U.S. Member of Congress with a reputation for being very hands-on. He decided to fly down to Guyana and figure out what was going on and took a small camera crew from NBC with him.

The reception was surprisingly courteous, with Ryan meeting Jones and many leading members of the church, all of whom assured the Congressman that all was just peachy in the compound; there wasn’t a gun in sight. At some point, however, somebody managed to slip Ryan a note that had a list of names of people that wanted to leave.

Alarmed, Ryan announced the next day that he was leaving, and there was plenty of room in his plane for anybody that wanted to join him. A few people, figuring they were finally safe, happily accepted this offer and Ryan’s cars started rolling toward the airfield, a few miles away.

However, as they started boarding the plane, a group of Jones’ paramilitaries arrived and opened fire, killing Ryan and several others on the spot, while wounding yet more.

The Massacre

Realising that killing a Congressman was the beginning of the end, Jones exhorted his people to kill themselves. Some accounts survived the incident, and it seems that Jones now brought to fruition the hatred and fear of the federal government he had cultivated in his followers. He claimed that paratroopers would now rain down and kill and torture everybody; the only escape was an early death.

Bowls of punch were prepared — in the retelling the drink became the instant lemonade Kool-Aid, while it was actually Flavor-Aid — and mixed in was cyanide and other poisons. According to the accounts, a surprisingly large number of people seemed willing; when Jones said the children should take it first, few parents objected.

Once the children, about 300, started dying, it was the turn for the adults. The handful of people that refused were forced to do so under threat of Jones’ bodyguard. A few somehow made it into the jungle, where they watched their fellow cult members die.

It’s unclear what happened to Jones himself: when the Guyana military arrived, alerted by the people in the plane, they found him dead of a gunshot wound. Maybe the great saviour had been unwilling to drink?

That question will likely remain a mystery forever: what we do know is that the Jonestown massacre is yet another example of what can happen when people believe too much in one cause, and especially one man.

Articles you may also like

What lies behind the war in Tigray?

Reading time: 7 minutes

At the core of the current war between the Ethiopian central government and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front is the realignment of politics and the contest for political hegemony. In my view, it is about Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed allying with the Amhara to destroy Tigrayan power. This is an attempt to consolidate his position and that of his Amhara supporters.

Supernova in the East V – Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History

Dan Carlin has just released the latest in his epic Supernova in the East podcast series. Well worth working your way through, earlier episodes of this series are here too if you need to catch up or start from the beginning. Supernova in the East V. Can suicidal bravery and fanatical determination make up for […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.