Reading time: 10 minutes

The Treaty of Waitangi, the influential historian Ruth Ross (1920-1982) remarked in 1972, is “a bloody difficult subject”. She should have known – she devoted most of her working life to trying to make sense of it, especially the text in te reo Māori.

That difficulty persists to this day.

By Bain Munro Attwood, Monash University

Discussion and debate in New Zealand about te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi has been dominated for decades by two kinds of discourse: history (or rather what is thought to be history) and the law.

Much of what has been taken for history about te Tiriti/the Treaty has been produced by those who have worked outside the universities in Aotearoa New Zealand. History is a discipline that doesn’t present many strong barriers to those who wish to participate in the conversations and controversies it can stir up.

Anyone, whether academically trained or not, can presume to do history, discuss and debate it. This has increasingly become the case as the practice of history has been democratised in recent times.

It’s also the case, as I point out in my new book, ‘A Bloody Difficult Subject’: Ruth Ross, te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Making of History, that only some of the story about te Tiriti/the Treaty that has had the most impact on public life in New Zealand has been produced in accordance with the scholarly protocols of the discipline of history.

This is because it takes the form of foundational history. This is a kind of historical work in which authors claim that a particular event or text – in this case the making of the Treaty/te Tiriti or the texts of te Tiriti and the Treaty – comprises principles, whether moral or legal, that created the very foundations of the nation.

Foundational histories

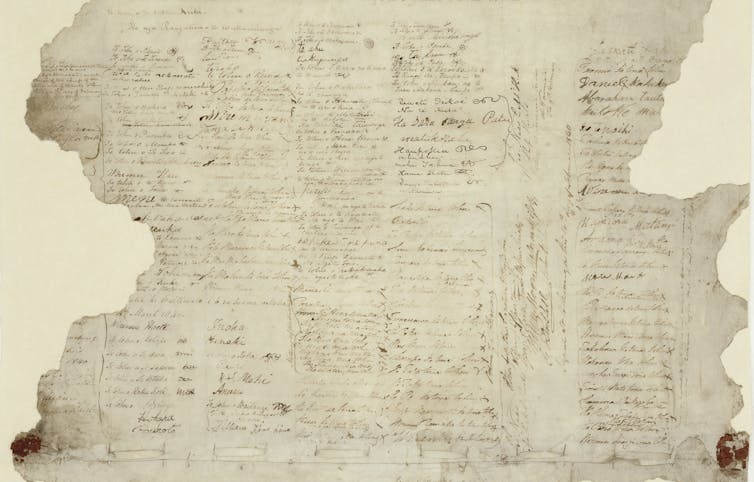

The story that has been told basically goes like this: the foundations of the New Zealand nation state – and the basis of its sovereignty – lie in the historic agreement between Māori and Pākehā that was made in 1840.

It amounts to a moral and legal contract between the two parties, both of whom entered into it with a sound enough knowledge of most of its terms, even though it was written in two languages (te reo Māori and English).

It claims that in this agreement Māori ceded sovereignty to the British Crown, but only on the basis that the Crown undertook to protect the chiefs’ rangatiratanga and their people’s rights of possession to all their lands and other treasures (taonga).

It acknowledges that these terms were repeatedly breached by the New Zealand state (also known as the British Crown) in the years after the Treaty/te Tiriti was made, and recognises that this inflicted enormous losses on Māori.

But it also asserts that the suffering they consequently suffered can be repaired (and the legitimacy of the nation redeemed) by the New Zealand state undertaking to honour the principles of te Tiriti/the Treaty.

This story about the Treaty/te Tiriti is an alluring one and it’s become very popular and powerful among many New Zealanders, both Māori and Pākehā – despite the fact that it amounts to a myth (or, as I will suggest later, because it does).

Founding myths

In everyday parlance, “myth” refers to a statement that is widely considered to be false. In using the word to describe foundational histories of te Tiriti/the Treaty I don’t exclude this connotation, but I have something more ambiguous in mind.

Most myths have a genuine link to a genuine past. Indeed, to be considered plausible, historical accounts must be able to show they have, at the very least, a partial relationship to past reality, and thus what is regarded as historically truthful.

In this case, there can be little doubt the British Crown had a moral purpose in choosing to make a treaty with the Indigenous peoples of New Zealand, namely to protect them against the ravages it had good reason to fear British colonisation would cause.

Likewise, there can be no doubt the Crown sought to make a treaty with the chiefs as though they were sovereign. Similarly, the Crown undoubtedly accepted Māori had some rights of possession in regard to land.

Yet the mythical account that foundational histories have provided of te Tiriti/the Treaty is one dimensional. They wrench from the past single traits such as the British Crown’s moral purpose and then proceed to portray them as though they’re the very essence and sum total of past reality. As a result, the story they tell about the historical agreement is egregiously incomplete.

Text and meaning

These myths achieve their effect not so much by falsifying the past as by distortion, oversimplification and omission of historical material that does not serve their creators’ purpose or runs counter to it. For example:

- They skirt around the historical fact that the British Crown often laid claim to sovereignty in New Zealand in the early 1840s on grounds other than the Treaty. These include the notorious legal doctrine of discovery that was the basis upon which the British Crown claimed much of the continent now known as Australia.

- They play down the fact that the British Crown didn’t regard Māori as fully sovereign and that it believed the chiefs needed to cede the limited sovereignty they had so the Crown could provide the protection it reckoned Māori needed.

- They ignore the fact that the British Crown did not define the precise nature of Māori rights of possession in land that it undertook to guarantee in te Tiriti/the Treaty, and that it also limited those rights by stipulating in the agreement that Māori could only sell land to the Crown.

However, the most problematic aspect of foundational histories, historically speaking, does not lie in any of these inconvenient historical truths. It lies in two other things:

- It assumes or pretends that a single interpretation can be given of what te Tiriti/the Treaty meant in the past or means in the present, thereby ignoring that any text has multivalent meanings, and especially one that’s in two languages.

- It assumes or claims that the party that offered the Treaty – the British Crown – conceived of the Treaty as a statement of principles that was to provide the foundations of the New Zealand nation, even though there’s little if any historical evidence to suggest the Crown’s agents saw it in this way.

History and the law

The problematic nature of foundational history as a means of enabling New Zealanders to understand the historic agreement made in 1840 has become all the greater in recent decades.

Most professional historians who have researched and written about te Tiriti/the Treaty have ceded their interpretive authority to what has become the dominant idiom in the interpretation of the Treaty – the law – which has told a story about the Treaty that mirrors that narrated by foundational history.

They have done this in several ways. They have sought to tell a story about te Tiriti/the Treaty that is useful to the law-makers, rather than just ensuring the stories they might tell will be relevant in some way to a consideration of the Treaty/te Tiriti in the New Zealand firmament, and the losses Māori have suffered since colonisation began.

They have misunderstood the nature of the story that lawyers have tended to tell about te Tiriti/the Treaty, treating it as though it amounts to history, even though the lawyers have made no such claim for their storytelling.

It might be argued that their confusion is understandable: when a professional historian hears, reads or sees a story about the past they are hard-wired to think the storyteller is making a historical claim about that past (in this case the Treaty/te Tiriti) – as distinct, say, from a legal, political or philosophical claim.

But this is nonetheless a mistake, rather like reading a work of historical fiction as though it’s a scholarly history. In the context of te Tiriti/the Treaty, a lawyer is primarily concerned with the present-day addressing and redressing of historical processes. Whereas a professional historian is, or should be, mainly interested in a disinterested retrieving and recounting of the past as it really was.

Further, historians have accepted the way lawyers have treated the Treaty as an act or event that’s first and foremost legal in nature, and especially constitutional, rather than considering it as an historical act or event that was principally political and diplomatic in character.

In doing all these things, professional historians have no doubt had the best of intentions. But there can also be little doubt they have crossed the razor-thin line that should separate historical scholarship from political or legal advocacy.

‘A bloody difficult subject’

As a result of what they have done, numerous professional historians have lent a degree of historical legitimacy to the story the law has been telling about te Tiriti/the Treaty that it wouldn’t otherwise have, and which it doesn’t warrant.

In effect, they’ve overreached themselves.

If they had practised their craft strictly in keeping with their discipline’s conventions, they would have found it impossible to produce the kind of mythical account of the Treaty/te Tiriti that they have provided by writing foundational history.

They would also have told a very different story about the historic agreement. This is not idle speculation but a matter of fact. As I discuss in one of the closing chapters of my book, there are several historians who have done just this.

Among the most important have been legal historians. Often trained in both the law and history, they dedicate themselves to trying to recover the past as it happened, rather than providing accounts of the kind the law requires in order to address contemporary problems.

These historians demonstrate that the law did play an important role in the making of te Tiriti/the Treaty, but not in the fashion imagined by lawyers. It was not so much the source of legal principles that determined the terms of te Tiriti/the Treaty, as it was a resource that was deployed in a highly pragmatic fashion by a large range of British players, who were seeking to advance a variety of political, economic and cultural goals that were momentary in nature.

Horizons past and present

What role, then, is the discipline of history best suited to play regarding te Tiriti/the Treaty and its place in contemporary public life in New Zealand?

By seeking to tell more truthful histories, historians might provoke New Zealanders to consider whether there are not intellectually sounder bases than the Treaty/te Tiriti for the political project it stands for.

Such histories could also provide – and indeed have provided – accounts that show how differently te Tiriti/the Treaty has been interpreted and understood over time, changing as the present has changed. In performing such a task, historians can demonstrate, in the words of an American historian, “how the horizon of the present is not the horizon of all that is in the world”.

In other words, the discipline of history’s primary intellectual justification probably lies in it being able to reveal that, once upon a time, there were ways of seeing things that are different to those that dominate in contemporary society. Works of history should surprise, even astound readers, by retrieving those ways of seeing and acting that are no longer known by most people.

In this sense, good history is a comparative exercise, drawing attention to differences and similarities between the past and the present. This could enable us to ask whether, in seeking to redress Māori loss and suffering, something is to be gained by broadening our horizons to include some of those that have largely disappeared from sight.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about the Treaty of Waitangi

Articles you may also like

The Mabo decision and native title

Reading time: 4 minutes

On June 3 1992, the High Court of Australia handed down its decision in the long-running case of Eddie Koiki Mabo and his compatriots from the Torres Strait island of Mer. Together they challenged the authority of the Queensland government to claim not just sovereignty but also ownership of the land comprising their ancestral home.

General History Quiz 84

1. What innovative device was invented to assist the ANZAC forces in their evacuation?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 5 – Audiobook

By Charles F. Horne (1870 – 1942),Rossiter Johnson (1840 – 1931) A comprehensive and readable account of the world’s history, emphasizing the more important events, and presenting these as complete narratives in the master-words of the most eminent historians. This is volume 5 of 22, covering from 843-1161 AD. Please leave this field emptyTell me about New […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.