Reading time: 5 minutes

In the movie The Life of Brian (1979), Reg, played by John Cleese, asks fellow members of the People’s Front of Judea:

… apart from the sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, the fresh water system and public health; what have the Romans ever done for us?

“Brought peace” is the answer he receives.

In hindsight, Christmas could be added to the list.

By Marguerite Johnson, University of Newcastle

When we think of the Romans, gift-giving, carol-singing and celebrating the birth of Christ don’t immediately present themselves. Waging wars, general oppression and a never-ending desire to rule the world are more likely to spring to mind.

But various Christmas traditions come from ancient pagan festivities, including the Roman celebration of the Saturnalia.

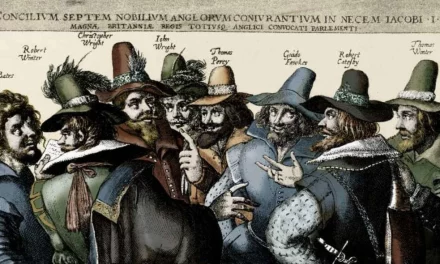

Historian and cultural investigator, Polydore Vergil (c. 1470-1555), was the first to record the similarities between certain pagan and Christian practices. He noted the connection between the predominantly English tradition, “The Lord of Misrule”, which occurred on Christmas Day and an equivalent custom of the Saturnalia. Both involved masters and servants or slaves swapping roles for a day.

Why the Romans permitted such silliness is based on the nature of the Saturnalia. Held in mid-December, the Saturnalia, a celebration in honour of the god Saturn, was characterised by the relaxation of social order and a carnival-like atmosphere.

Saturn, once the principal deity of the Italians, was the god of time, agriculture and things bountiful. He reigned over the Golden Age, an era of peace, happiness and plenty. Indeed, the pleasures associated with the Golden Age were perhaps re-enacted in the Saturnalia itself.

The Saturnalia celebrated the god in his role as overseer of a season of anxiety. Winters were harsh and food sometimes scarce. And as the days became shorter and the earth symbolically died, the seasonal time needed to be commemorated and the god kept happy.

The Saturnalia was a lead-up to the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, recorded as December 25 in the Julian calendar.

With revelries and hijinks, feasting and the cessation of formal business, the Romans looked forward to the coming of the light of the sun. With the return of spring, there would be renewed fertility. Crops would grow and farm animals would give birth, providing another year of bounty and full bellies.

As part of the revelries, the Romans exchanged gifts: candles, signet rings, toothpicks, combs, tooth paste, baby rattles, hairpins, woolly slippers, warm caps, tablecloths and, yes, even socks and the Christmas puppy! These were exchanged during or after a feast, served by the head of the household and perhaps his children while the slaves enjoyed their time off.

Saturn’s association with gift-giving has led scholars like Samuel L. Macey to link him with Santa Claus. But, as Macey knows, Saturn had a shadowy side and, like many Roman deities, there were skeletons in his closet! Someone who decides to eat his children as a means of maintaining power, for example, isn’t an ideal Santa prototype. Then again, some kids find Santa pretty scary.

As television was not yet invented, and the internet light years away, the poor old Romans had to occupy their Saturnalian leisure time with human interaction. They enjoyed games, gambled, played dress-ups and recited poetry (some of a risqué nature). Drinking, the modern scourge of the holiday season, was also a feature of the Saturnalia. While some of us take offence at the barbed comments at Christmas get-togethers, the Romans simply regarded them as a ritualised part of the upside-down world of the silly season.

Besides the Saturnalia, there was another important Roman festival with influential ties to Christmas: the celebration of the Unconquered Sun on December 25. According to the fourth century almanac, the Calendar of Philocalus, there is mention of a celebration of the “Unconquered” on December 25, which is most likely a reference to the “Unconquered Sun.”

In the same manuscript, December 25 is also listed as the birth of Jesus.

The Calendar of Philocalus is therefore cited by some scholars as potential evidence for the coalescence of the festival of the Unconquered Sun with the celebration of the birth of Christ. David M. Gwynn suggests: “The commemoration of Christ’s birth on 25 December … appears to have originated in the west, in part to provide a Christian counterpart to the birthday of the Sun.”

By the end of the late Roman period, Christmas was part of the Christian calendar. The pagan festivals may have officially disappeared but traces of the old ways remained.

And so began the long history of Christmas.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Podcasts about pagan traditions in Christmas rituals:

Articles you may also like:

Weekly History Quiz No.274

1. When did the Exxon Valdez oil spill occur?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.