Rachel Wood, Australian National University

Radiocarbon dating has transformed our understanding of the past 50,000 years. Professor Willard Libby produced the first radiocarbon dates in 1949 and was later awarded the Nobel Prize for his efforts.

Radiocarbon dating works by comparing the three different isotopes of carbon. Isotopes of a particular element have the same number of protons in their nucleus, but different numbers of neutrons. This means that although they are very similar chemically, they have different masses.

Wessex Archaeology

Rachel Wood, Australian National University

Radiocarbon dating has transformed our understanding of the past 50,000 years. Professor Willard Libby produced the first radiocarbon dates in 1949 and was later awarded the Nobel Prize for his efforts.

Radiocarbon dating works by comparing the three different isotopes of carbon. Isotopes of a particular element have the same number of protons in their nucleus, but different numbers of neutrons. This means that although they are very similar chemically, they have different masses.

The total mass of the isotope is indicated by the numerical superscript. While the lighter isotopes 12C and 13C are stable, the heaviest isotope 14C (radiocarbon) is radioactive. This means its nucleus is so large that it is unstable.

Over time 14C decays to nitrogen (14N). Most 14C is produced in the upper atmosphere where neutrons, which are produced by cosmic rays, react with 14N atoms.

It is then oxidised to create 14CO2, which is dispersed through the atmosphere and mixed with 12CO2 and 13CO2. This CO2 is used in photosynthesis by plants, and from here is passed through the food chain (see figure 1, below).

Every plant and animal in this chain (including us!) will therefore have the same amount of 14C compared to 12C as the atmosphere (the 14C:12C ratio).

Dating history

When living things die, tissue is no longer being replaced and the radioactive decay of 14C becomes apparent. Around 55,000 years later, so much 14C has decayed that what remains can no longer be measured.

Radioactive decay can be used as a “clock” because it is unaffected by physical (e.g. temperature) and chemical (e.g. water content) conditions. In 5,730 years half of the 14C in a sample will decay (see figure 1, below).

Therefore, if we know the 14C:12C ratio at the time of death and the ratio today, we can calculate how much time has passed. Unfortunately, neither are straightforward to determine.

The amount of 14C in the atmosphere, and therefore in plants and animals, has not always been constant. For instance, the amount varies according to how many cosmic rays reach Earth. This is affected by solar activity and the earth’s magnetic field.

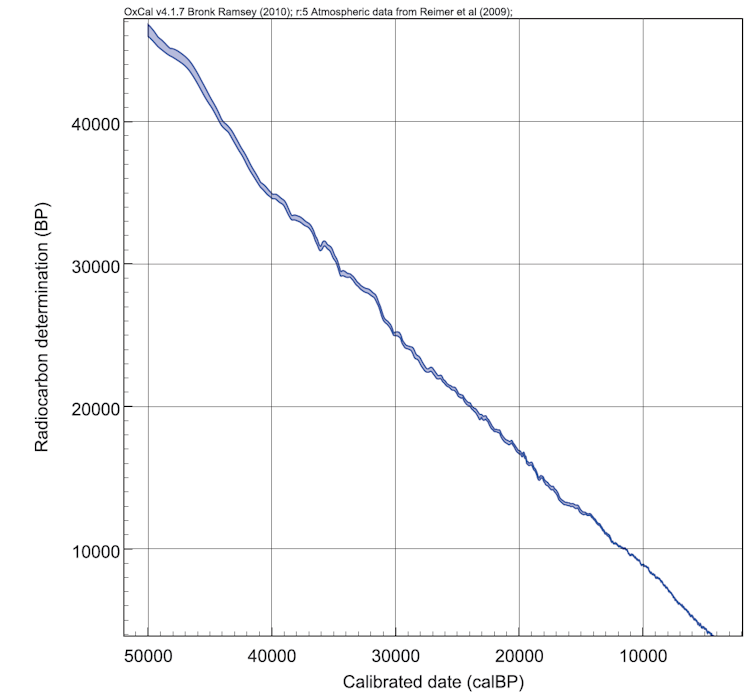

Luckily, we can measure these fluctuations in samples that are dated by other methods. Tree rings can be counted and their radiocarbon content measured. From these records a “calibration curve” can be built (see figure 2, below).

A huge amount of work is currently underway to extend and improve the calibration curve. In 2008 we could only calibrate radiocarbon dates until 26,000 years. Now the curve extends (tentatively) to 50,000 years.

Dating advances

Radiocarbon dates are presented in two ways because of this complication. The uncalibrated date is given with the unit BP (radiocarbon years before 1950).

The calibrated date is also presented, either in BC or AD or with the unit calBP (calibrated before present – before 1950). The calibrated date is our “best estimate” of the sample’s actual age, but we need to be able to return to old dates and recalibrate them because new research is continually used to update the calibration curve.

The second difficulty arises from the extremely low abundance of 14C. Only 0.0000000001% of the carbon in today’s atmosphere is 14C, making it incredibly difficult to measure and extremely sensitive to contamination.

In the early years of radiocarbon dating a product’s decay was measured, but this required huge samples (e.g. half a human femur). Many labs now use an Accelerator Mass Spectrometer (AMS), a machine that can detect and measure the presence of different isotopes, to count the individual 14C atoms in a sample.

This method requires less than 1g of bone, but few countries can afford more than one or two AMSs, which cost more than A$500,000. Australia has two machines dedicated to radiocarbon analysis, and they are out of reach for much of the developing world.

In addition, samples need to be thoroughly cleaned to remove carbon contamination from glues and soil before dating. This is particularly important for very old samples. If 1% of the carbon in a 50,000 year old sample is from a modern contaminant, the sample will be dated to around 40,000 years.

Because of this, radiocarbon chemists are continually developing new methods to more effectively clean materials. These new techniques can have a dramatic effect on chronologies. With the development of a new method of cleaning charcoal called ABOx-SC, Michael Bird helped to push back the date of arrival of the first humans in Australia by more than 10,000 years.

Figure 2: a calibration curve showing radiocarbon content over time.

Establishing dates

Moving away from techniques, the most exciting thing about radiocarbon is what it reveals about our past and the world we live in. Radiocarbon dating was the first method that allowed archaeologists to place what they found in chronological order without the need for written records or coins.

In the 19th and early 20th century incredibly patient and careful archaeologists would link pottery and stone tools in different geographical areas by similarities in shape and patterning. Then, by using the idea that the styles of objects evolve, becoming increasing elaborate over time, they could place them in order relative to each other – a technique called seriation.

In this way large domed tombs (known as tholos or beehive tombs) in Greece were thought to predate similar structures in the Scottish Island of Maeshowe. This supported the idea that the classical worlds of Greece and Rome were at the centre of all innovations.

Some of the first radiocarbon dates produced showed that the Scottish tombs were thousands of years older than those in Greece. The barbarians of the north were capable of designing complex structures similar to those in the classical world.

Other high profile projects include the dating of the Turin Shroud to the medieval period, the dating of the Dead Sea Scrolls to around the time of Christ, and the somewhat controversial dating of the spectacular rock art at Chauvet Cave to c.38,000 calBP (c.32,000 BP) – thousands of years earlier than expected.

Radiocarbon dating has also been used to date the extinction of the woolly mammoth and contributed to the debate over whether modern humans and Neanderthals met.

But 14C is not just used in dating. Using the same techniques to measure 14C content, we can examine ocean circulation and trace the movement of drugs around the body. But these are topics for separate articles.

If you’d like to learn more about radiocarbon dating, www.c14dating.com is an excellent starting point.

Rachel Wood, Research Officer, Radiocarbon Facility, Australian National University

This article was originally published in The Conversation.