Reading time: 8 minutes

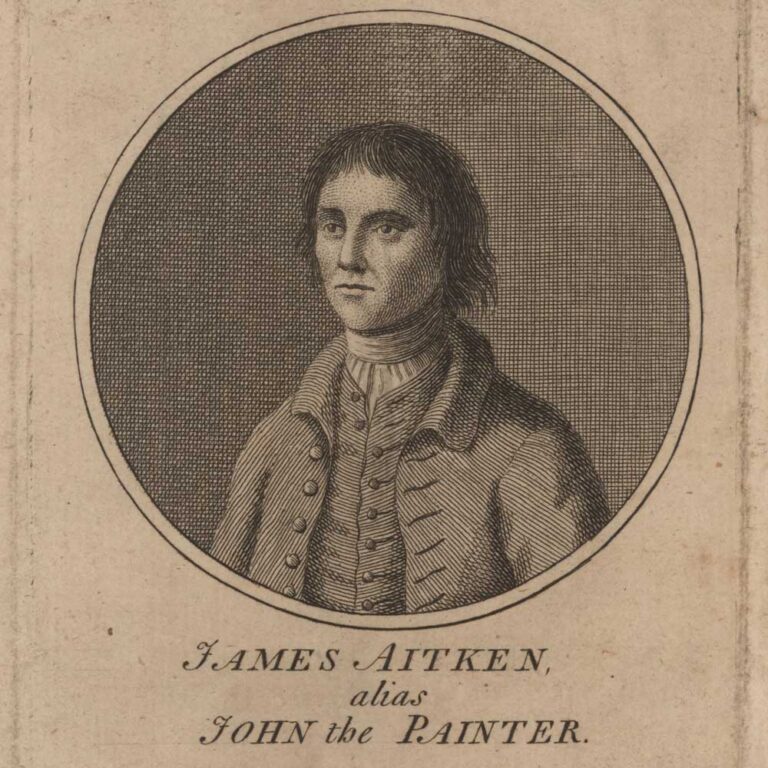

Opposition to the British Crown during the American War of Independence took many forms, none more notorious than the malicious designs of James Aitken (alias ‘John the Painter’).

By Ralph Thompson, The National Archives.

Opportunities – in crime

Born in Edinburgh in 1752, James Aitken (aka James Hill, aka John Boswell) served his apprenticeship to a painter in that city and thereby secured the familiar title of ‘John the Painter’. He ran through countless aliases in his adult life (which was mostly as a petty thief). While Aitken was not a victim of Georgian England’s ‘Bloody Code’, he habitually offended the capital statutes against petty property crime.

In 1773 having evidently failed to obtain an army commission, he came to London and worked for a while as an honest journeyman, before running into debt. Finding the murky criminal underworld offered more opportunities, he embarked on a varied career as a highwayman, burglar, and robber.

Meanwhile, posters describing him and advertising for his capture led him to emigrate to the American colonies. Lacking funds and fearing that his crimes would be detected, Aitken negotiated an indenture in exchange for a voyage to Jamestown. Having no intention to work out of his term, he escaped from Virginia and eventually went northward through Maryland and the mid-Atlantic colonies, to settle in New York.

It was during this period that he encountered revolutionary rhetoric, and claimed that he had been harassed by British troops for being a suspected Whig patriot. He was present during the Boston Tea Party (of December 1773). According to his own account he returned to England in May 1775, following the trade of painter at Titchfield and other places.

However, on taking up his criminal life once more and conceiving a growing sympathy for the Patriot cause of the colonies he had recently fled, he developed a scheme of political sabotage. Some writers have suggested that Aitken was motivated by a desire to escape his life of insignificance and poverty, and that his striking a blow on behalf of American liberties would, he reasoned, be recognised and handsomely rewarded with a commission in the American Continental Army.

A campaign of terror

The Royal Dockyards, Aitken believed, were vulnerable to attack. He was convinced that one determined act of arson would cripple the Royal Navy by destroying its harboured ships and – more importantly – the dockyards and hemp walks used to build and refit the fleet.

Although Aitken was allegedly no criminal mastermind, there was an integrity to his plot that seriously alarmed the Admiralty once the details emerged. The dockyards were critical, and as Aitken perceived, scarcely guarded. While Aitken planned to strike at five different dockyards in sequence, he lacked the charisma to form a cell for a co-ordinated insurgent attack.

Despite being a wanted criminal for his other crimes, Aitken travelled freely to several dockyards to determine their vulnerability. However, after meeting the American envoy Silas Deane in Paris, he came away with the deluded notion that he had the full diplomatic backing of Deane and the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Aitken returned to England and was instructed to contact the American spy and double-agent Edward Bancroft, to whom Aitken revealed at least some of his plans. Using his training as a painter to mix chemicals and solvents, Aitken engaged the services of several individuals in constructing crude incendiary devices, with the intention of burning down the highly flammable buildings in the Royal dockyards.

Over the course of several months, Aitken attacked facilities in Portsmouth and Bristol, creating the impression that a band of saboteurs was on the loose for his campaign of terror in England.

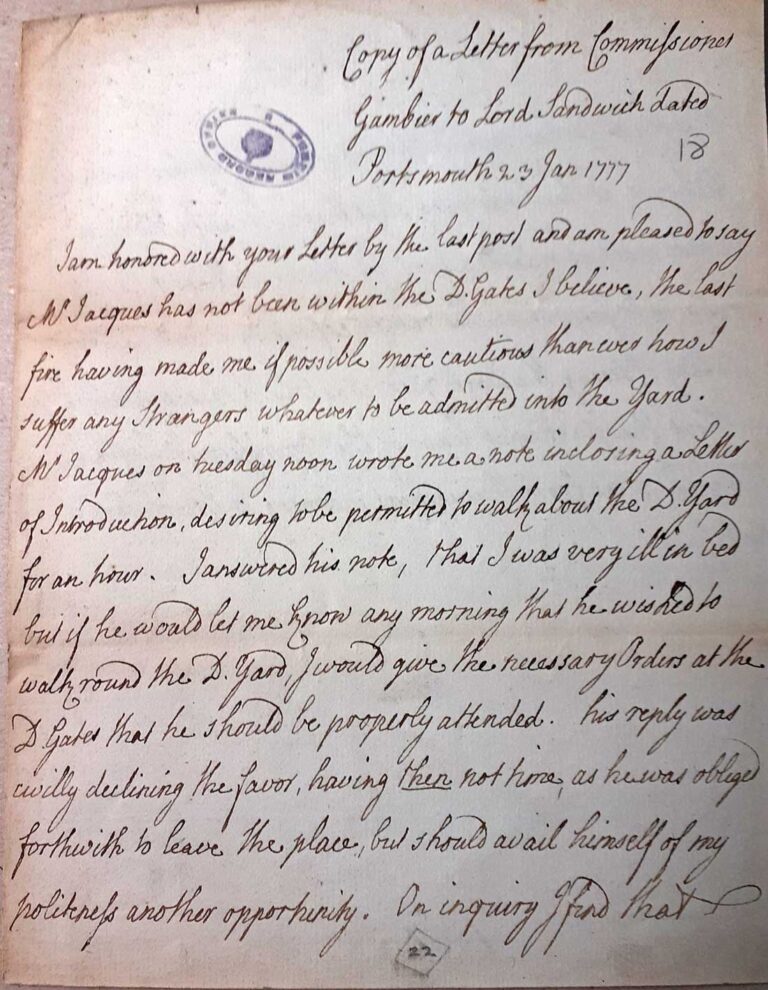

Arriving in the City of Portsmouth in December 1776 with firebombs, he eventually ignited three homemade incendiary devices in the dockyard rope warehouse and slipped away, with the flames soon gutting the brick building. The cost of his malicious attack would eventually be estimated to have been around £20,000 (worth almost £2 million today).

Ironically, Admiralty investigators were unsure at first if it was an act of arson. Though the warehouse burned to the ground, destroying its valuable naval stores, the damage to the port itself was negligible. James Aitken, however, was convinced he had struck a great victory for the American revolutionary cause.

The country on alert

Aitken made his way to London where his contact Dr Bancroft, who was utterly horrified by his tales of treachery, would have nothing to do with his schemes. Afraid that Bancroft would turn him in to the authorities, he left the capital and headed for the south-west.

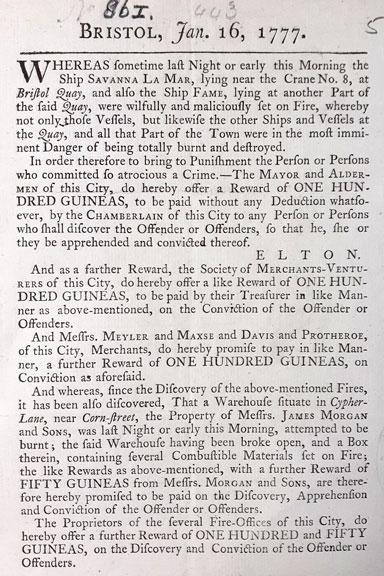

Finding the sizeable naval dockyard at Plymouth to be too well guarded, he settled on an ambitious plan to engulf the densely populated port of Bristol – dockyard and city alike. However, after targeting three ships, he only managed to burn one vessel.

While causing little actual damage, his actions raised a rapidly escalating panic at revolutionary incendiaries abroad. It did not take the authorities long to link them to Portsmouth. The second firebomb at Bristol put the whole country on alert as security was tightened at every port.

Prime Minister Lord North’s Tory administration became aware that saboteurs had targeted their shipyards but had no idea it was the work of a single man. Several other totally unrelated fires were put to his credit, leading to the assumption that it was the work of a whole gang.

As Aitken had been seen fleeing from the site of his first (unsuccessful) attempt on Portsmouth, the government circulated a description of him, and an enormous reward was consequently offered by the Admiralty at the urging of the magistrate Sir John Fielding.

Aitken’s undoing

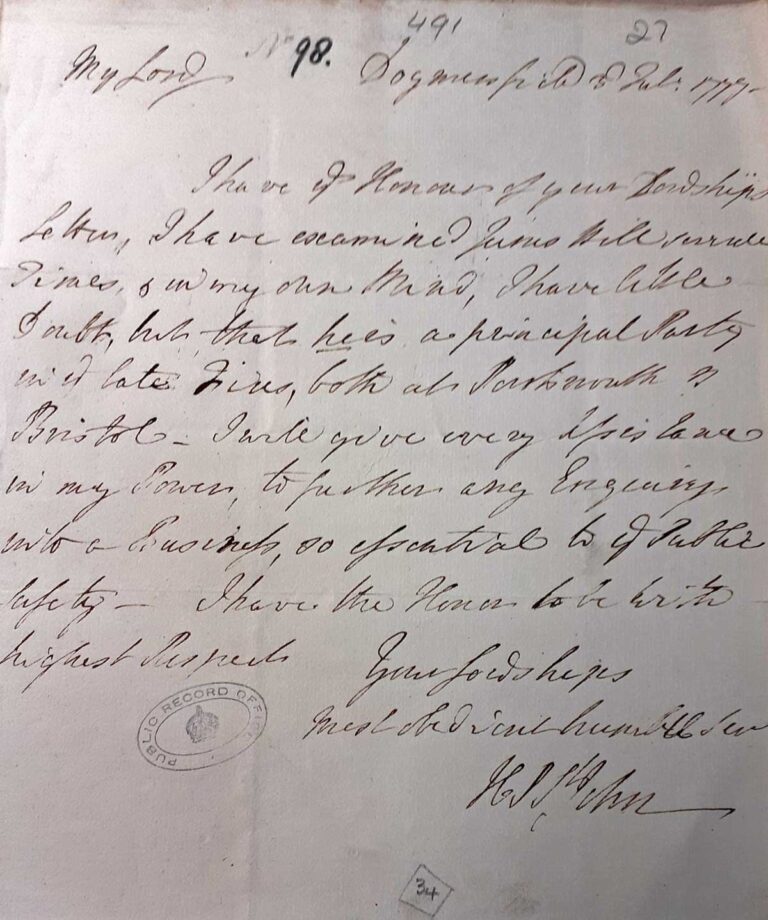

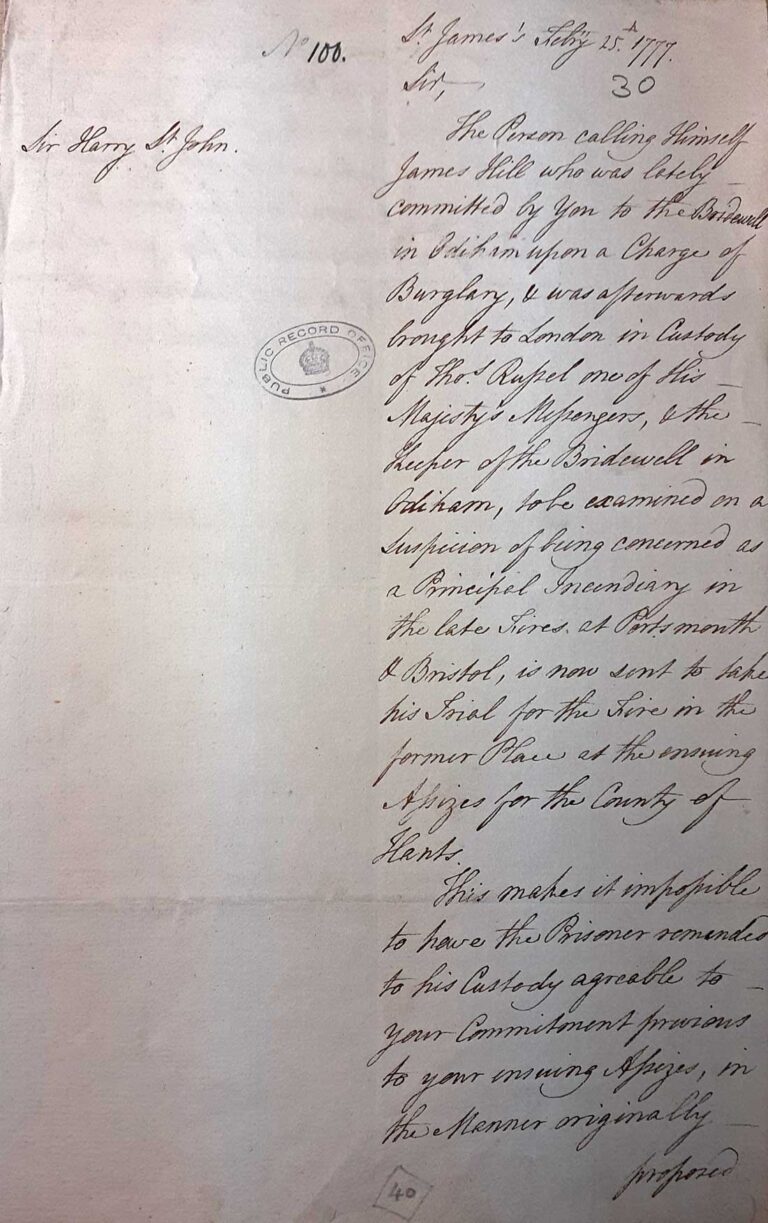

Deciding to abandon his conspiracy and flee to France, James Aitken attempted to rob a house in Hampshire which proved to be his undoing. Being recognised as fitting the description of the unknown Scotsman that had been published in Fielding’s Hue and Cry publication, he was taken into custody by a King’s Messenger (a courier of diplomatic documents, with powers to enforce the law) and examined at the Odiham Bridewell.

During the course of his imprisonment in Odiham, the authorities were unsuccessful at gaining sufficient evidence against him, other than his pleading guilty to burglary (which could be pardoned by ‘taking religion’, to avoid the death sentence). Aitken was transferred to the New Prison, Clerkenwell, where the government used John Baldwin, a young expatriate American, as an informer to gain Aitken’s trust by convincing him of his revolutionary sympathies.

Aitken provided Baldwin with a great deal of incriminating evidence, particularly information about his dealings with Silas Deane and the important mission he believed he had been entrusted with. This became important in locating witnesses and strengthening the State’s case against him. Soon the entire plot was exposed, and James Aitken doomed.

Having been finally examined on 24 February, Aitken was taken from London for trial at Winchester.

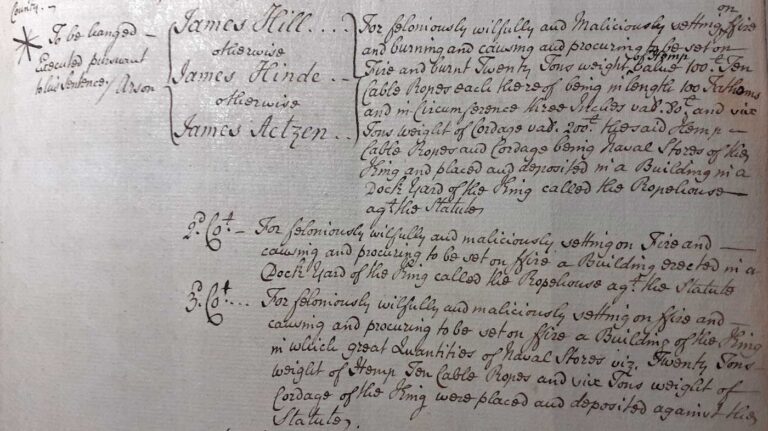

While his acts of sabotage on behalf of the American colonial cause were undoubtedly treasonous, the only charge laid against him was for burning the rope house at Portsmouth Dockyard contrary to the provisions of the Dockyards Protection Act of 1772, an offence which carried the death penalty. He was subsequently found guilty after a single day’s hearing and sentenced to death.

On 10 March 1777, James Aitken – as James Hill, but also known as ‘John the Painter’, an ‘enemy of the Navy’ – was hanged from the mizzenmast of HMS Arethusa. It had been removed and set up outside the dockyard gates so as many people as possible could witness his end.

His remains were gibbetted and displayed at Fort Blockhouse, across the harbour at Gosport, for several years. Ultimately, his was the only execution for arson in Royal Dockyard history.

This article was originally published by The National Archives.

Podcasts about treason against the Crown

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 202

1. Writing in the 1380s, who was the first to refer to Valentines Day on the 14th of February?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.