Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

60 years after its initial construction, the memory of the Berlin Wall remains a potent symbol of the Cold War.

Of all of history’s global conflicts, perhaps none has been as heavily based on symbolism than the Cold War; because there was little direct military action, (other than proxy wars), and the “war” was founded almost purely on competing economic principles and ideologies, the Cold War was in essence a war of propaganda.

By Michael Vecchio

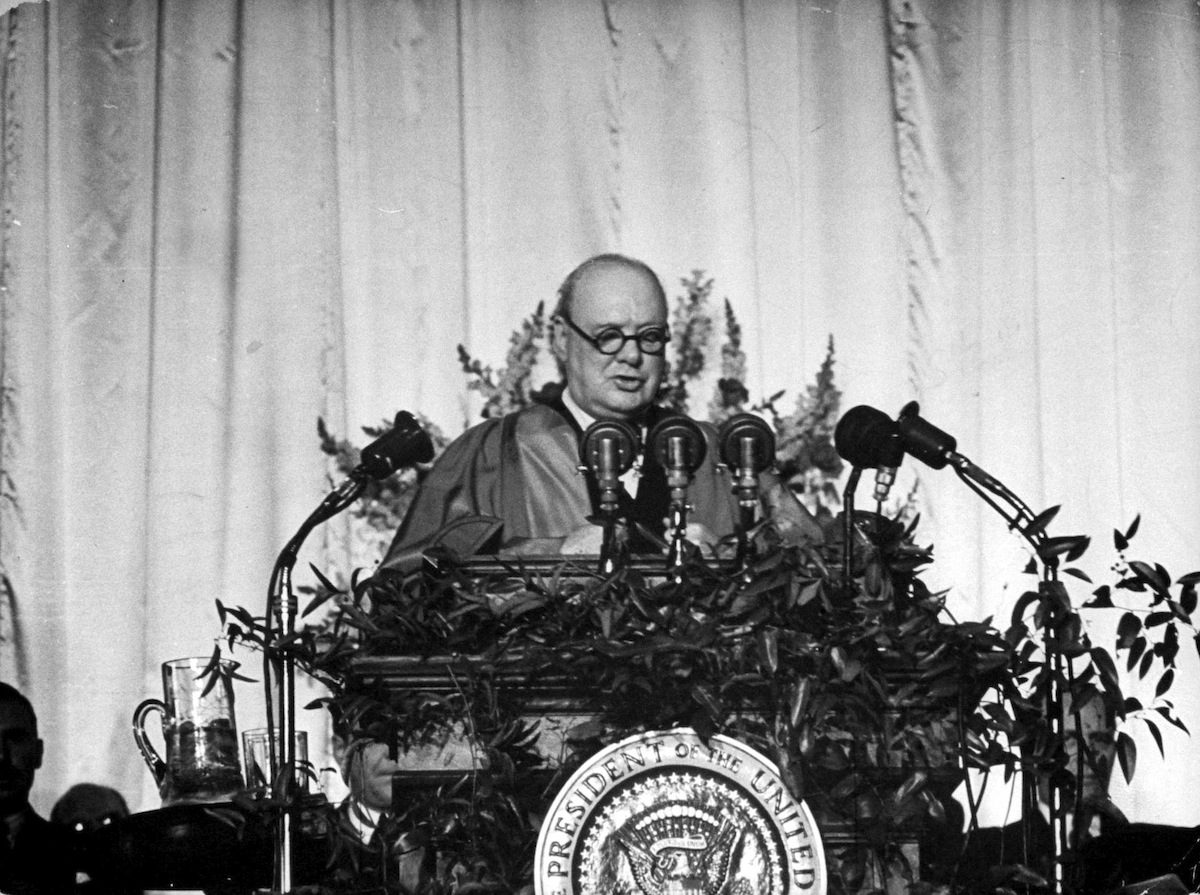

But to spread propaganda, an efficient system of control and dominance is needed; although the United States had its share of virulent anti-Communist rhetoric (including the infamous actions of Joseph McCarthy), Americans continued to live in a relatively free society with access to reliable information. For citizens of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, described by Winston Churchill as living behind an Iron Curtain, propaganda was king.

READ MORE: The Cold War, Churchill’s Iron Curtain, and the Power of Imagery

In any ideological battle, the fight to control the narrative is paramount, and the Iron Curtain was a succinct and powerful use of symbolism for those in the West. The Soviet regime was expert in keeping people within its borders and subversive information out. And yet for all the symbolism of the Iron Curtain term, suddenly on an August night in 1961, the symbolism became all too literal; the Berlin Wall had appeared.

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the fallen German capital, became a playground of sorts for the victorious Allies; Stalin’s Red Army was thirsty for the continued humiliation of Germany and eager to further expand its Communist Empire. To avoid further tensions, the Western Allies agreed to let much of Eastern Europe fall under the Soviet sphere of influence. This included Germany itself, which would be divided into two nations, East and West Germany. But what about the city of Berlin?

What would amount to an ultimate sense of shame for German citizens, the beloved capital would too be divided into East and West; although the Western portion of the city was still in communist controlled East Germany, it retained its ties to the democratic West and the struggle to undermine the new dictatorship in the Eastern half of the European continent. This would be a point of much contention for the puppet state of East Germany, who knew that a Berlin under firm control would be the only way to maintain its grip on power.

READ MORE: East Germans Pressured Soviets to Build Berlin Wall

For a period of 16 years, (1945-1961), nearly three million East Germans fled to the West; West Germans and other foreign citizens were permitted to enter East Berlin, but East Berliners needed a special pass, or Propiska (internal passport). But by 1961 the situation became untenable as the East German government struggled to keep its population in line and win the ongoing propaganda war of superior ideology. And so it was on the evening of August 12, 1961 that East German Communist Secretary Walter Ulbricht signed an order to officially create a barrier separating East and West Berlin.

The Iron Curtain had now physically manifested itself, as members of the Stasi and other police forces began erecting a series of concrete barriers and barbed wire fences across the political division of Berlin. Over time the structure evolved into a formidable obstacle, standing nearly 12 feet high and running 27 miles long (43 km); there were 302 guard towers and an astonishing 55,000 explosive devices along the wall. Reinforced with barbed wire, spikes, bunkers, and metal gratings, attempts to cross over, or escape into the West was notoriously difficult, and guards in the towers were frequently known to shoot any potential trespassers.

All the Ways People Escaped Across the Berlin Wall

From its construction until its eventual destruction in 1989, the Berlin Wall was a literal symbol of death and tyranny, and at least 150 people were killed attempting to cross over. It is estimated that up to 100,000 people attempted to circumvent the wall in its 28 years. For the East German authorities, the wall was justified as a means of protecting its people from Fascist forces and was officially known as the Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart, while much of the outside world saw it as an oppressive tool that further solidified the “barbarity” of communism.

Ironically, the wall became a counter propaganda tool for the West, who used its existence to illuminate the injustices of Soviet dominance, while for East Germany its very purpose was to prevent Western propaganda from entering its confines.

Frequently vandalized and damaged, the obstinate presence of the Berlin Wall emboldened critics and dissidents in the West and those behind its concrete; US Presidents John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan both famously delivered speeches pleading with the East German government (and in turn the politburo in Moscow) to end the repression. In the case of Reagan, his imploration came with the now memorable words of “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

By 1989 a wave of pro democracy uprisings finally broke through, and many of the Soviet Union’s satellite states began to defect; Berlin’s mighty wall would too fall victim to the tide of change. The East German government finally opened up its borders to the West on November 9, effectively eliminating the need for a wall. Jubilant crowds with sledgehammers and other tools smashed the structure, as thousands of others scaled it in defiance of the dark chapter of their recent history. Soon Germany would be reunited as one nation once again.

While remnants of the wall remain on display (as an eternal reminder of the errors of the past), it is rightfully placed as a symbol of a different age.

And yet 30 plus years later, and 60 years after its initial construction, the Berlin Wall and the ideology of control and propaganda remain in the minds of all Germans and those around the world who have fought against injustice and oppression. The Cold War may have ended, but its lessons remain, and there is perhaps no better symbol of its legacy than the memory of the Berlin Wall.

Articles you may also like

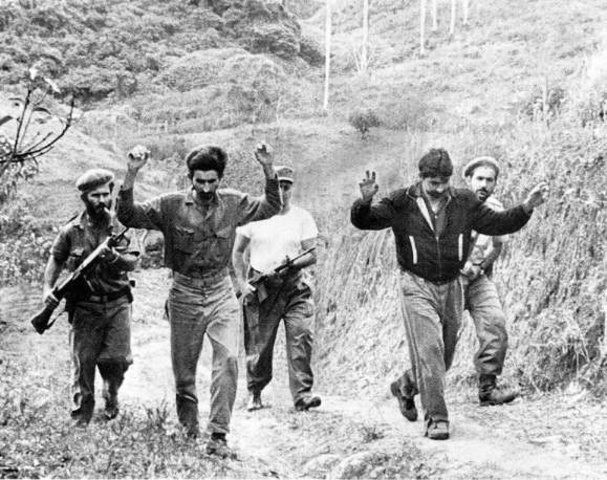

Hubris and Miscalculation: The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion

HUBRIS AND MISCALCULATION: THE FAILURE OF THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION By Michael Vecchio The threat of Nazi villainy had been defeated, however another authoritarian threat rapidly placed over half of Europe behind what Winston Churchill called an “Iron Curtain”. The Soviet Union’s aggressive brand of Communism startled much of the Western world, but perhaps […]