Reading time: 7 minutes

Never mind the roads, rivers were the arteries of the Roman Empire, carrying food, fuel and livestock along important ancient trade routes.

The expression “All roads lead to Rome” encapsulates the might of the Roman Empire, but the arteries which carried its lifeblood – food, fuel, livestock and luxuries – were not roads, but rivers.

By Dr Tamara Lewit, University of Melbourne

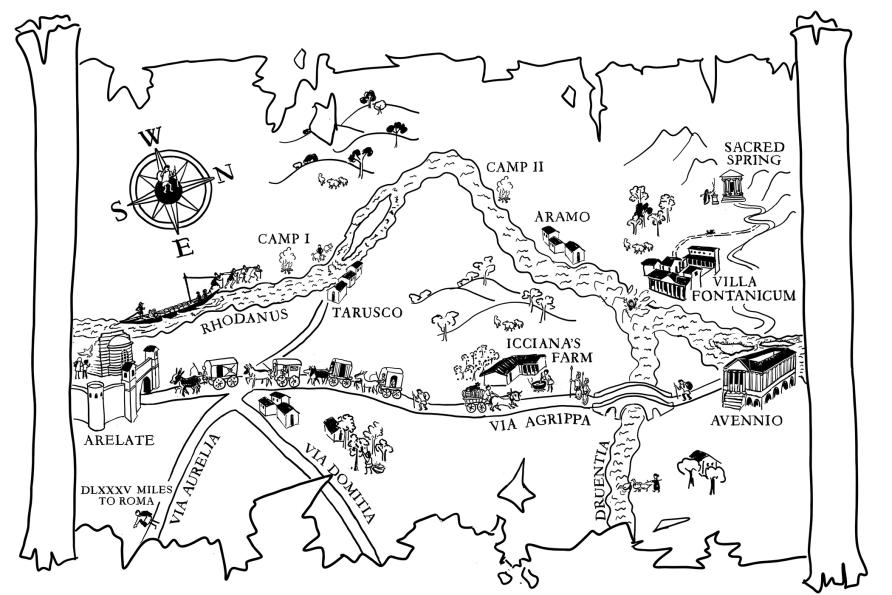

My interest in Roman river transport was spurred while researching the children’s novel A Message Through Time, written by my sister, Anna Ciddor. In the book, a follow up to The Boy Who Stepped Through Time, two modern children slip through time to ancient Roman Gaul. They take on a difficult and dangerous quest to a sacred spring, journeying upriver against the current.

The neglected world of Roman river craft which I discovered was a revelation.

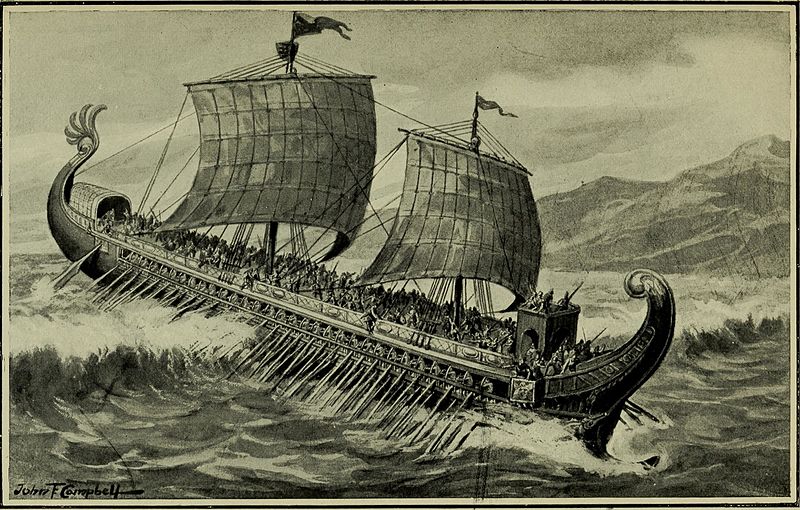

Sea ships have long captured archaeological and public attention, with treasure troves of sunken amphorae from hundreds of wrecked ships carrying oil, wine and fish sauce scattered across the Mediterranean Sea.

Their timbers are mostly lost to time, although well-preserved, deep-water wrecks have been brought to light using remotely operated vehicles and underwater cameras in one of the largest maritime archaeological undertakings ever staged, the Black Sea Maritime Archaeological Project.

As an archaeologist researching ancient trade in wine and oil, I was familiar with these finds. But river transport was probably more frequent and important than sea ships to the everyday life of the Roman Empire. While dangerous winter seas were closed to sailing, river boats transported goods year round.

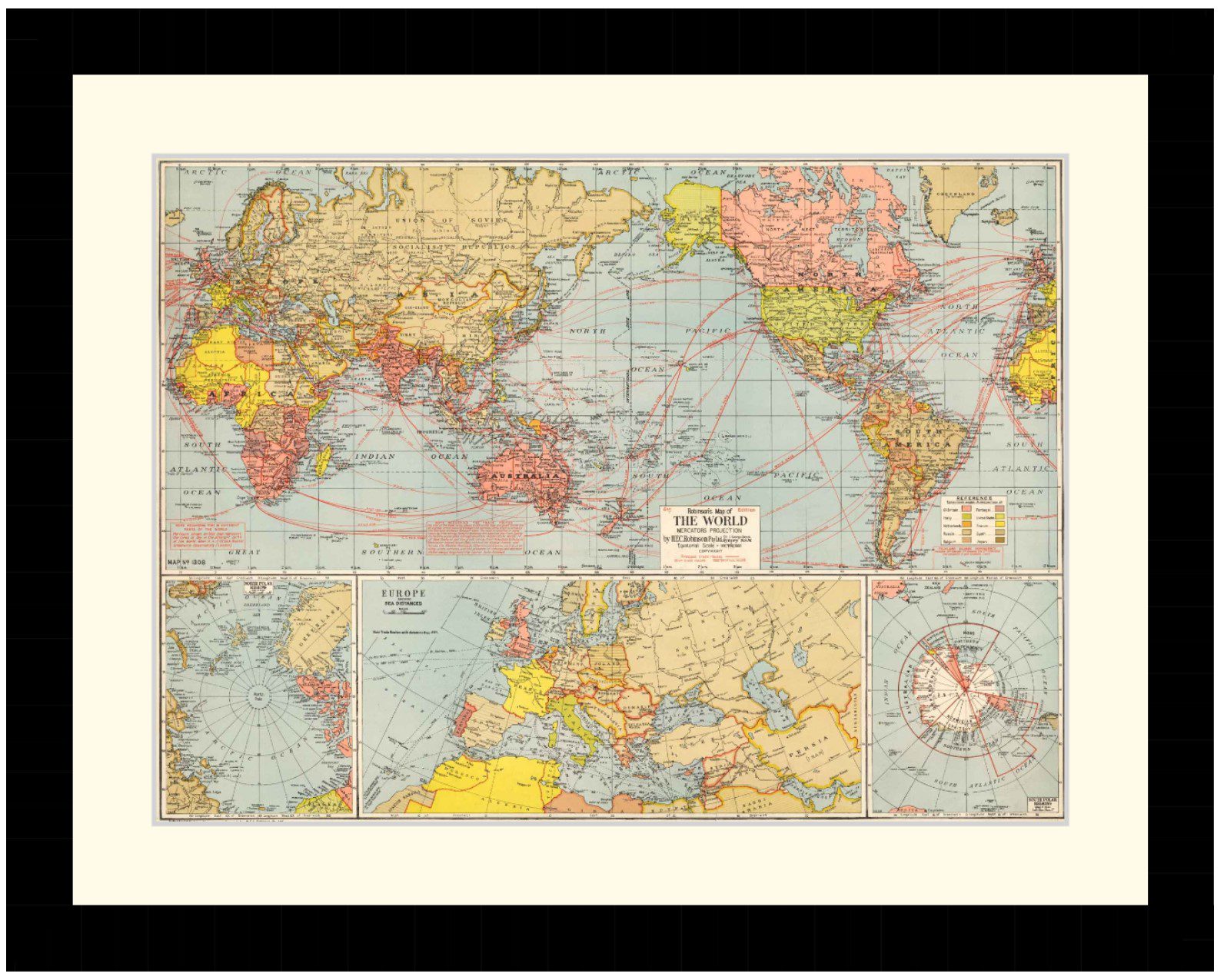

It was via rivers that imports travelled from coastal ports to inland towns and farms. Cities relied on rivers to bring food, building materials and fuel from their rural hinterlands.

The arteries of the Empire were rivers like the Guadalquivir, channelling massive supplies of olive oil from modern-day Spain to Rome; as well as the Rhine and Danube, feeding the armies on the frontiers.

River sources were sacred places – inspiring our fictional sacred spring in A Message Through Time – where coins, sculptures and precious objects were thrown into the water as offerings to the gods. Bronze statuettes and 5,000 gold, silver and bronze coins were discovered at the hot springs of San Casciano dei Bagni (Italy) in 2022.

In 2004, an almost-complete river barge was discovered at Arles in the south of France, a few metres below the surface of the Rhône. This was a major route linking the Mediterranean with Germany and Alpine regions.

Dubbed the Arles-Rhône 3, the boat’s excavation, restoration and eventual museum display cost some 10 million euros and has provided us with unique insights into the realities of Roman river travel.

This barge measures 31 metres long, but less than three metres wide and about one metre high. A pot filled with charcoal was used as a hearth, scorching the surrounding timbers. Bowls, two plates and three cups suggest three sailors lived on board, one of whom engraved his initials (AT) on a plate.

They had tools for cutting wood and levering cargo as well as a single small oil lamp. Caius and Lucius Postumius (perhaps brothers, or a father and son), whose names are branded on several wooden parts, may have been the owners.

Hidden under the mast’s wooden foot was a votive coin, a lucky charm placed there in the unfulfilled hope of safe travel.

The boat’s long, narrow shape was well-suited to the strong Rhône current, but the vessel had no oars or sail. Found still loaded with building stone from quarries to the north of Arles, it had travelled downstream with the river current, guided by the large wooden steering oar.

A prowman diverted obstacles and tested the water depth with a two metre pole, pointed at each end, which was also found in the wreck.

The clue to how the barge travelled upstream – presumably loaded with Mediterranean products, local salt, wool or even live sheep – lies in the mast. Only 3.7 metres high, worn by ropes and lodged at the very front of the barge – this was not a mast for a sail but rather for towing.

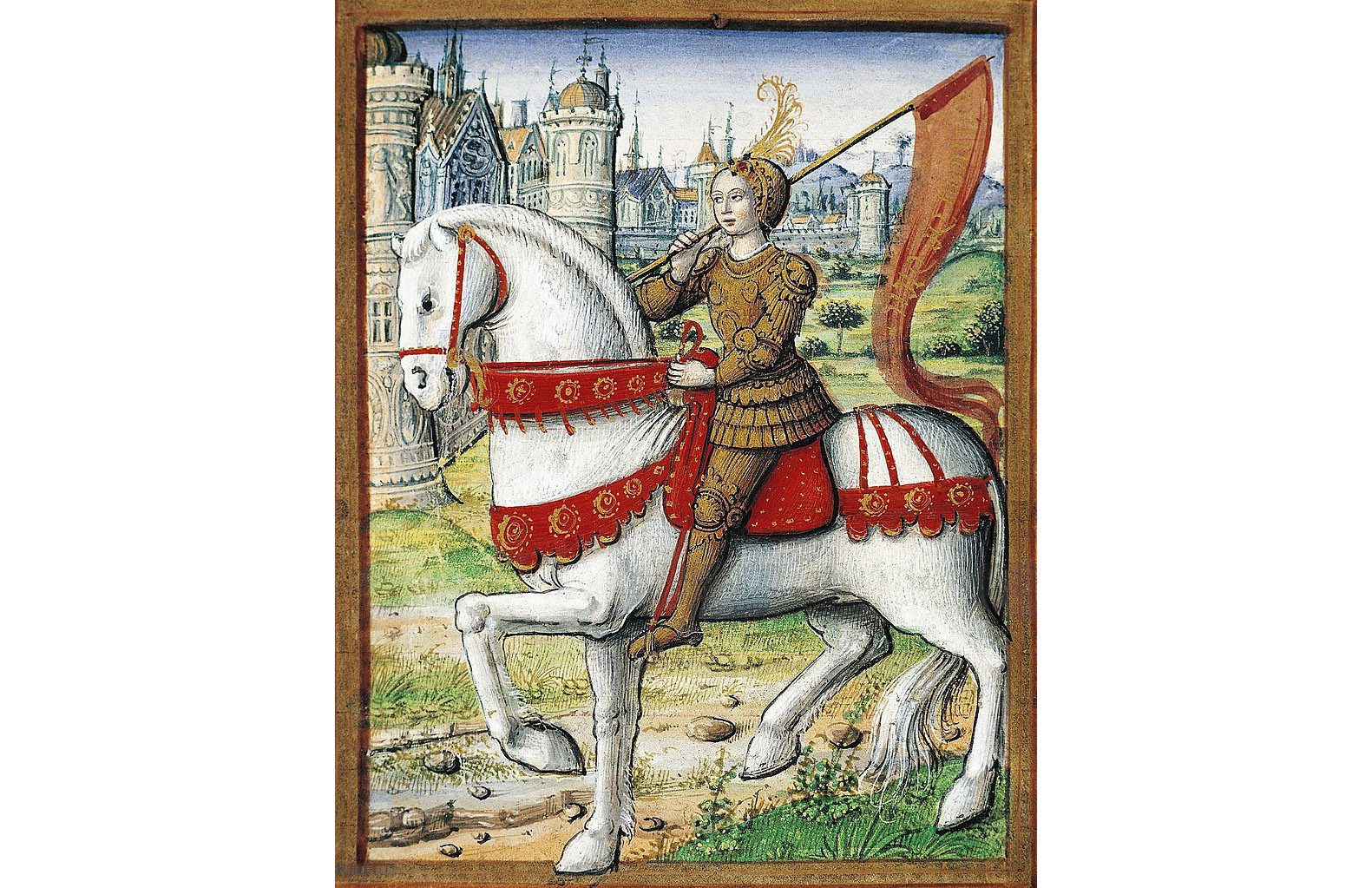

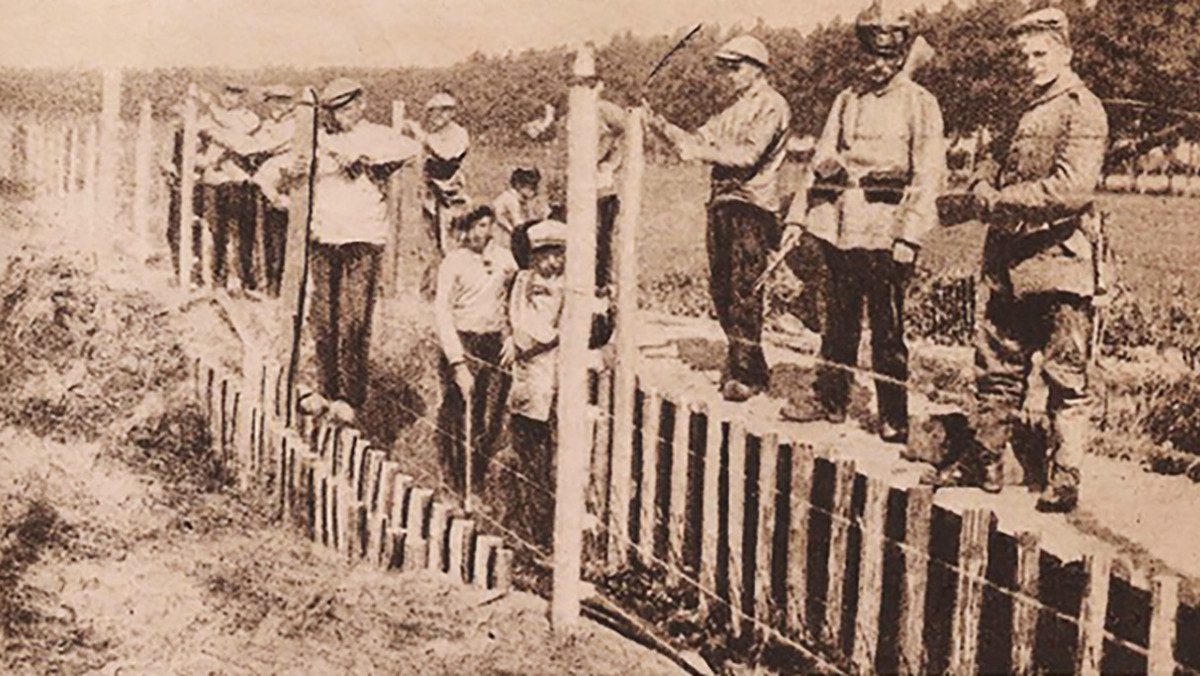

From Roman times until the 16th century, barges like this were towed upstream by men dragging the heavy boat and its cargo. Medieval documents say each hauler pulled 1.5 tonnes – more than the weight of a Mini Cooper car.

The Arles-Rhône 3 weighs eight tonnes and when loaded with cargo it must have been hauled by at least 20 men. A bigger barge weighing 19 tonnes, found in the river at Lyon, would have required around 50 haulers.

The work was desperately hard. In the Middle Ages, it was known as ‘blood haulage’. Backs bent, the men hung onto ropes tied to the towing mast, steadying themselves with walking sticks and shouts.

Many other kinds of boats also plied the rivers of the Empire. Some were used for fishing in rivers and lakes, supplying important protein sources for both rich and poor.

The fourth-century poet Ausonius mentions Moselle salmon “with flesh of rosy red, … destined to form a course at some dazzling dinner” but also cheap pike “fried in cook-shops rank with the fumes of his greasy flavour”.

Fishing boats on the lake (or “Sea”) of Galilee appear many times in the Gospels, and the remains of a small boat radiocarbon dated to this period have been excavated there.

A third-century CE mosaic found at Althiburus in Tunisia contains images and names of 25 different kinds of sea and river boats – but our upper-class textual sources seldom describe everyday craft in detail.

Instead, they tell us about Emperor Caligula’s pleasure boats, described by the Roman historian Suetonius as having “sterns set with gems, particoloured awnings, huge spacious baths, colonnades, and banquet-halls, and even a great variety of vines and fruit trees; that on board of them he might recline at table from an early hour, and coast along the shores of Campania amid dancers and musicians”.

Two 70-metre luxury cruise boats belonging to Caligula lay for centuries in the waters of Lake Nemi in Italy. There were attempts to raise them from the 15th century, which finally succeeded when the lake was drained in 1929.

These ships, with their magnificent bronze sculptures and mosaics, were put in a museum but, sadly, the wooden boats were destroyed by fire during World War II. Part of one of their mosaics was rediscovered serving as a coffee table in a New York apartment in 2013.

But rich finds like this do not tell us the true story of the Romans.

It is the humble timbers and pots of small river boats like the Arles-Rhône 3 which speak to us of ordinary people, ordinary lives and their extraordinary importance.

This article was originally published in Pursuit.

Podcasts about riverine trade in the age of Rome:

Articles you may also like:

Australian pilots in the fight for control over the Mediterranean

Reading time: 11 minutes

The Siege of Malta, a two-year ordeal of bombs, heat and dust, was one of the most important battles of the Mediterranean theatre in World War Two. Few of the victories in North Africa and Italy would have been possible had the island fallen to the Axis. In this article, we let Australian pilots who defended Malta tell their stories.

General History Quiz 101

1. The Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek alphabets are all derived from the alphabet of which group?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

A Short History of Russia – audiobook

A SHORT HISTORY OF RUSSIA – AUDIOBOOK By Lucy Cazalet (1870 – 1956) A Short History of Russia by Lucy Cazalet is a helpful introduction to the people, places, and events that shaped Russia, the largest country in the world. While covering the bullet points of Russian history, the author expands to greater detail when talking […]

The text of this article is republished from Pursuit in accordance with their republishing policy and is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives 3.0 Australia (CC BY-ND 3.0 AU).