Reading time: 11 minutes

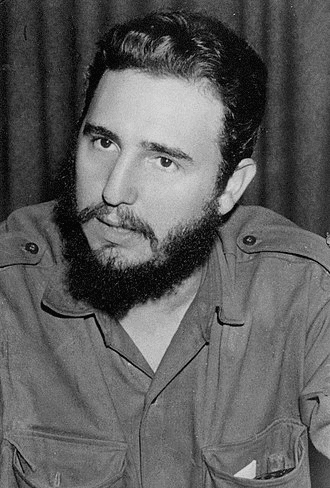

The 1959 Cuban Revolution resulted in rule by a communist regime under Fidel Castro. This period also saw counter-revolutionaries forming anti-Castro movements, complicating the already tumultuous political landscape. In 1961 the United States would intervene with a force made up of Cuban exiles, the infamous ‘Bay of Pigs’ invasion.

By Madison Greco

Historical Context

March of 1952 marked the beginnings of political reforms and revolution in Cuba. Army general and politician, Fulgencio Batista, seized power of the nation from the president at the time, Carlos Pio Socarras. Batista cancelled the upcoming elections, proclaimed himself president and began to implement a new political system he described as a ‘disciplined democracy’. This system was nothing short of a one man dictatorship, and although a small portion of the public would support this new national endeavour, the majority would not. Resistance to the regime was on the rise, and many groups became violent in their protests, becoming a full-blown armed rebellion against the government. This conflict that would last 7 years until Fidel Castro’s success in 1959.

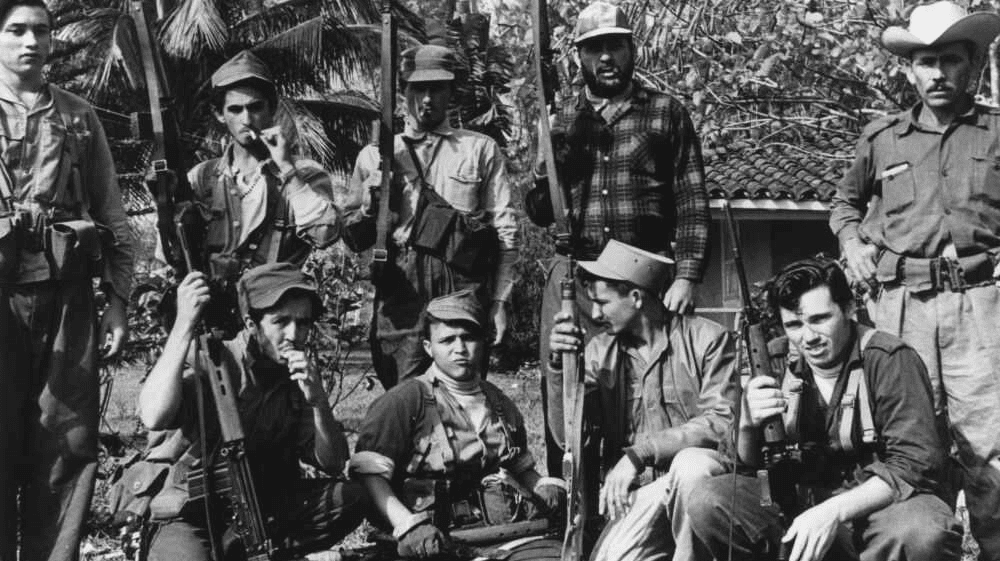

The multitude of armed resistance groups, nicknamed ‘anti-Batista groups’ executed attacks on Batista’s forces throughout the island. One of the most famous groups, the National Revolutionary Movement, was formed by professor of philosophy Rafael Garcia Barcena and consisted of mostly middle class society seeking true democracy for their nation. This group was heavily armed, and carried out many attacks on Batista’s army in attempt to oust the government. However, no group is more famous than the ’26th of July’ movement, lead by Fidel Castro.

Between 1956 and 1959, Castro would lead his guerrilla army on a whole host of attacks. Based in the Sierra Maestro mountains, the group was named after the date the revolution began, the 26th of July 1953. It would not be until 1965 the party was renamed as the ‘Communist Party of Cuba’, in conjunction with the Marxist-Leninist ideology adopted by Castro and his government from 1959 onwards. Throughout their three years of active resistance they were able to push Batista’s forces into total retreat, culminating on the 31st of December 1958 as Batista resigned and fled into hiding. After this success, Castro installed a puppet politician as President until February 16th of 1959, when he would take total control and declare himself leader of the new ‘democracy’.

Despite this claim, it was abundantly clear that Castro’s regime was not a democracy at all. He would defend this by saying that the people had a right to protest, and a right to express to him what they desire: that was ‘democracy’. This caused widescale uproar and lead to significant counter-revolutionary resistance to this newly established government.

Cuban Resistance to the Revolution

Similar to the resistance formed against Batista, militant groups were assembled to protest Castro’s leadership. Hundreds of armed attacks, bombings and attempts on the leadership took place, usually originating from the mountains, where resistance groups would create their bases, just as the 26th of July Movement led by Castro did 4 years prior.

Castro and his government wanted to eliminate this resistance, however they knew the measures they could use had to be limited. There was international scrutiny of the new ‘democracy’ and obvious similarities between Batista and Castro. Castro’s forces knew they could not utilise the same overt physical torture utilised by the former president. Instead, they would opt for intense psychological torture, arresting hundreds of those engaged in the counter-revolutionary resistance and subjecting them to solitary confinement, starvation and threats along with a multitude of other torture techniques.

The government struggled to keep the details of the arrests and torture under wraps, and soon enough the press began publishing extensively about the details surrounding the suppression of resistance. This caused public outrage and further criticism of Castro for the torture methods used on his political prisoners. However in January of 1960, the government mandated a ‘clarification’ for every newspaper, restricting and limiting what could be published. This would begin the intense censorship utilised by the Cuban government to control the population and political message spread throughout the nation.

Some of these resistance groups and individuals were supported by the United States, including the Cuban Revolutionary Forces that would spearhead the utter failure of the Bay of Pigs Invasion. But why was the US involved? Why did they want to stop Fidel Castro?

The United States and Formation of Revolutionary Force

The 1960s was a tumultuous diplomatic landscape on a global scale; the Cold War was in full swing, communism was gaining ground in many decolonising countries. Tensions between the United States and the Soviet union were at an all time high, in part due to the aggressive leadership of Nikita Khrushchev. Cuba increasingly became a part of this conflict. It was initially not clear whether Castro would associate his regime with the USSR or remain a part of the non-aligned movement. However, a series of disputes, misunderstandings and brinkmanship lead to Cuba and the USA becoming increasingly antagonistic towards each other.

This made Castro concerned that the USA would invade Cuba or attempt to remove him from power. This meant he cultivated a closer relationship with the USSR as protection from the USA. This must be viewed in the context of the very active approach the USA was taking in removing leaders that were not seen as being aligned with ‘western interests’. The USA had recently assisted in the overthrow of the democratically elected leaders of Iran and Ghana. Castro believed that the USA would do the same in Cuba.

Conflict flared soon after Castro took leadership, with an oil dispute in late 1960. The Cuban oil refineries, controlled by western companies such as Shell, Esso and Standard Oil, were told to buy oil from the USSR rather than the USA. Due to intense pressure from the United States these companies refused. Castro responded by nationalising all oil refineries, taking total control to ensure his policy in support of the USSR would be upheld. This also marked a major step towards the communist system being created in Cuba, as more major industries becoming government owned, a key feature of a communist regime.

The next year would involve continuous disputes between the two governments over a multitude of issues. US diplomatic policy in this period had difficulty separating nationalist movements founded on socialist principals from regimes that were closely aligned with the USSR. This was complicated by the support the USSR provided to many resistance groups in decolonising countries in order to increase Soviet influence. US opposition to almost any socialist government became somewhat self fulfilling, as these governments saw that their best path as being to support the USSR in order to gain protection from the USA.

The Truman doctrine further complicated this process, the USA saw the USSR providing support to the Cuban regime as an unjust intrusion into their sphere of influence. The Cuban regime saw Soviet support as a legitimate means of maintaining their national self determination.

By 1961, the CIA had drawn up plans to assassinate Castro using any means necessary, such as with a diving suit contaminated with toxic poison or an ‘exploding seashell’- these elaborate ideas and the exact attempts made by the United States to assassinate the leader may never be fully known.

President Eisenhower instructed the CIA to plan an invasion to attack Castro’s forces and overthrow the government. $13 million dollars was the allocated budget for the removal of Castro from power, and establish a government that would act in the national interest of Cuba, and presumably the United States. Richard M. Bissell Jr. was charged with overseeing plans for the invasion.

The process of assembling the force began by recruiting those opposed to the regime; this involved the training of Cuban paramilitary forces, disseminating anti-communist propaganda and the development of an intelligence operation in the nation. The CIA would infiltrate anti-Castro exiles whilst providing weaponry to resistance forces, however these were not particularly successful. Eisenhower approved plans for a ‘Special Group’ prior to the 1960 elections, in which John F Kennedy would succeed Eisenhower as President of the United States of America.

Intense discussions were held with Kennedy to ensure his continued support for the plan developed under the Eisenhower government, and by the end of January the President would sign off on the plan, nicknamed ‘Operation Pluto’. This would involve a force of 1,000-1,500 men invading an inlet of the Gulf of Cazone, known as the ‘Bay of Pigs’. The manpower was made up almost solely of Cuban exiles who had been trained since 1960 under CIA paramilitary development programs. The invasion was set for the 17th of April of 1961, being coordinated almost solely by the CIA and relevant governmental organisations.

The Invasion and Aftermath

Cuba heard about the invasion, and expected a US-backed force in the coming weeks. On the evening of the 16th of April, a false landing was staged at Bahia Honda, loaded with speakers playing sounds of gunfire, advancing battleships and other weaponry to lure the Cuban forces away from the Bay of Pigs area, the anticipated attack zone. This reportedly lead Fidel Castro himself away from the area, leaving the destined attack zone unprotected- or so they thought.

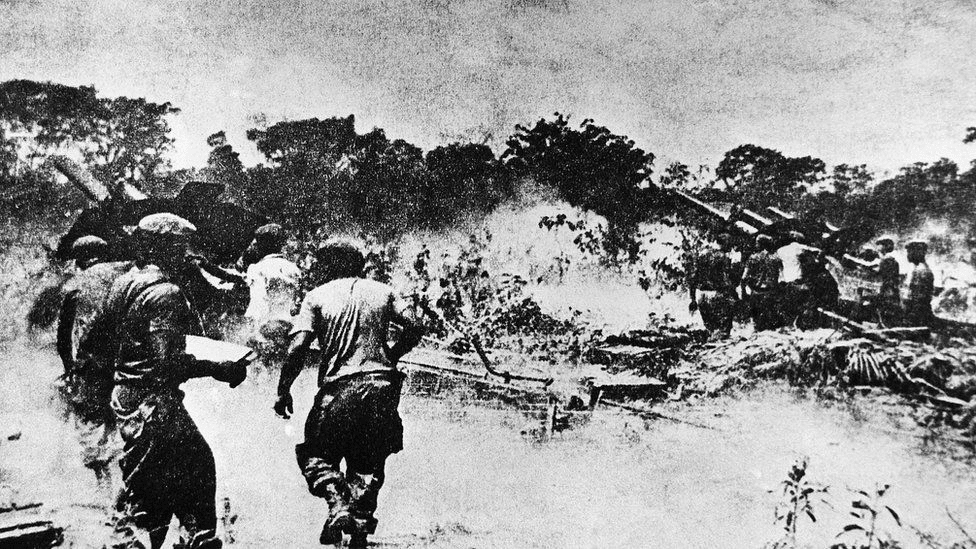

1,400 soldiers would arrive on the beach, advancing into the Cuban jungle. They were met by experienced Cuban militia who quickly formed defensive positions. The early hours of the 17th saw the invasion hang in the balance, proving to be a matched fight for both sides.

Airstrikes against Cuban military bases and aircraft were planned for the 17th, however, the Kennedy administration called these off. This was in order to provide the USA with plausible deniability as to their role in the invasion. They feared that if US aircraft were shot down over Cuba then Castro would have proof of the USA supporting the invasion. Many historians see this decision as the dooming the invasion. The small number if anti-Castro exiles, denied air support, had little chance of success. The Cuban Army was able to mobilise thousands more soldiers and aircraft to defeat the invasion. Although casualties amongst the exiles were not significant, the forces were pushed back towards the beach and had almost no chance of success nor escape.

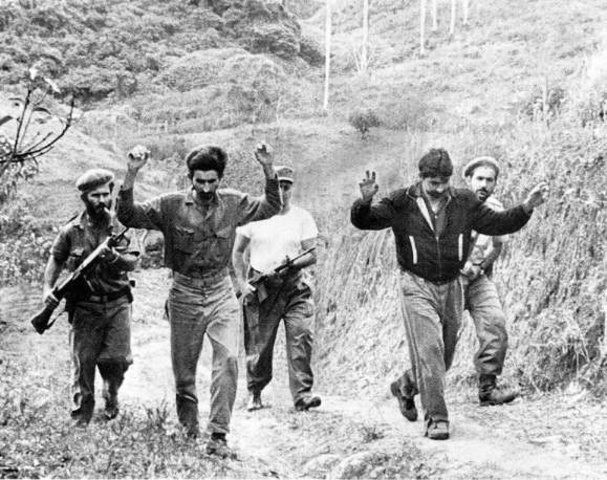

By day three, 1,200 soldiers had been captured, 48 were dead and 10 had been executed by firing squad; the invasion was an utter failure. The United States had totally underestimated the power of the Cuban military, and the cancellation of the US air support exacerbated this fact by allowing Cuban air power to contribute. In late 1961, Castro would offer to return the captured soldiers for the sum of $28 million USD. The USA did not take up the offer.

These prisoners were tortured, eventually being charged with treason and sentenced to 30 years in prison. Interestingly, Brazil intervened on behalf of the United States to stop the Cuban government from executing the captured soldiers.

The failed invasion severely embarrassed the Kennedy administration and made Castro understandably very concerned about future U.S. intervention in Cuba. On 21 April, in a State Department press conference, Kennedy said: “There’s an old saying that victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan… Further statements, detailed discussions, are not to conceal responsibility because I’m the responsible officer of the Government…” This, in turn, increased the fear of communism throughout the United States and lead to the nation becoming significantly more wary of their neighbours. This would be significant in Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, in addition to other future dealings with Cuba and their increasingly close partner, the Soviet Union.

The Bay of Pigs invasion set the stage for the Cuban missile crisis. The invasion fulfilled Castro’s greatest fear, a US invasion of Cuba to remove him from power. He saw closer ties to the USSR as being his way of protecting himself and his country from this. In this fear he was absolutely correct, during the Cuban missile crisis the USA debated whether to launch an invasion of Cuba using conventional US military forces.

Read More – How the Bay of Pigs invasion began – and failed – 60 years on

Castro would remain in power until 2018, when he would be replaced by Miguel Díaz-Canel in an election of the national assembly. The communist regime in Cuba persists to this day, however the nation has chosen to adopt a more softline communism style increasing international trade and opening policy to fit the ever-changing world.

Articles you may also like

The Cold War Ignites: The Berlin Blockade and Airlift

Once the centre of Nazi ideology and power, the German capital of Berlin was extremely important not only in the Allies quest to defeat Hitler, but in the rebuilding of Europe after War’s end. And yet while the Allies were indeed united in their collective opposition to the Third Reich, their similarities ended there, especially […]

Hubris and Miscalculation: The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion

HUBRIS AND MISCALCULATION: THE FAILURE OF THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION By Michael Vecchio The threat of Nazi villainy had been defeated, however another authoritarian threat rapidly placed over half of Europe behind what Winston Churchill called an “Iron Curtain”. The Soviet Union’s aggressive brand of Communism startled much of the Western world, but perhaps […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.