Reading time: 8 minutes

On 23 August 1720 at the Council Chamber in Whitehall, the Privy Council issued an order to the commissioners of His Majesty’s Customs ‘to prevent the landing any goods, passengers, or seamen from on board any ships coming from the Mediterranean’. Diplomats and statesman had been in correspondence for weeks about the worrying state of affairs developing in the south of France. Writing to Secretary of State James Craggs, the diplomat Robert Sutton related ‘the melancholy news of a pestilential distemper being crept into Marseille by the infection of some bales of cotton brought from Sidon (in modern day Lebanon)’. Other letters reported that the seamen on the said voyage had died, with many others taken sick and transported to infirmaries. Four porters, who had opened the goods carried on the ship, died suddenly as the distemper spread from ship to shore killing as many as 24 people in one street. Quarters of the city were barred up and houses and their contents were burned. The plague had hit Marseille.

Plague epidemics were not rare, though they were no less alarming. The London plague, which had killed approximately 100,000 people in 1665, was likely in the memory of many of those hearing the news from France. Throughout the centuries, local and national governments across Europe had developed and employed a range of public health measures to control the outbreak of infections. From the 14th century onwards, quarantine (from the Italian quaranta meaning ‘forty’, referring to a 40-day period of isolation) was the recommended practice to impede the spread of disease with the infected either ‘shutt up’ in their houses or transferred to Pest Houses.

By Philippa Hellawell

In early modern Europe, there were multiple theories concerning the causes and spread of disease. One of the dominant explanations was that disease could spread through poisonous vapours that passed through the air called miasmas. However, at the same time, there were also theories surrounding contagion and the spread of disease through contact with diseased persons, animals and objects. From the burning of sweet herbs to purify the air to the airing and destruction of goods, responses to the plague were varied to reflect the varied ways of thinking about disease.

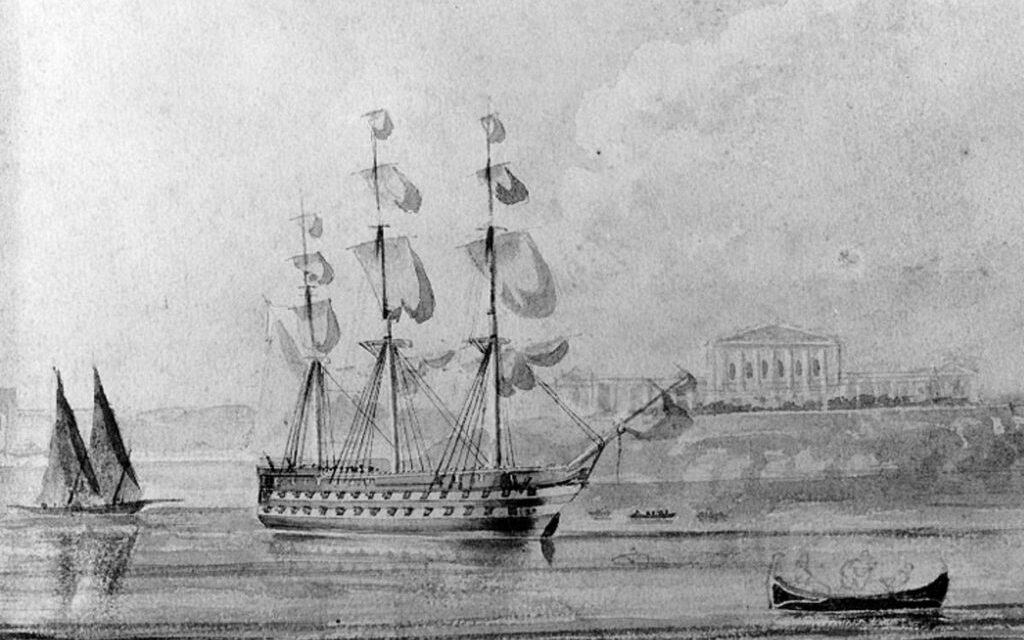

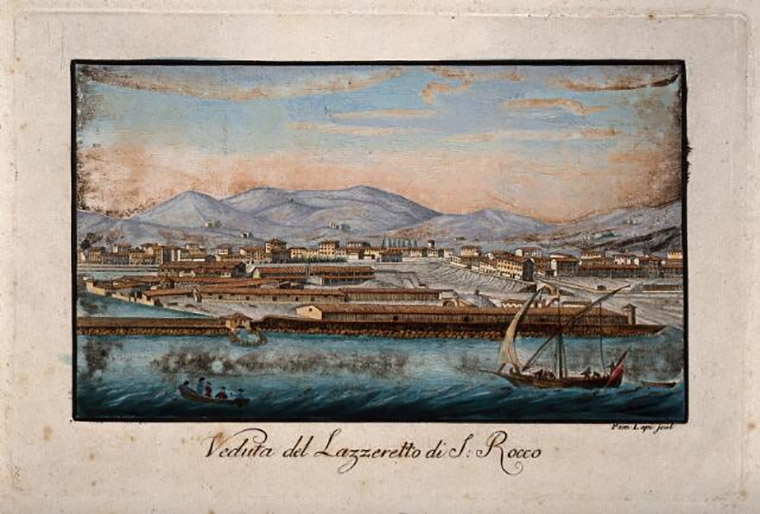

In times of plague, ships, seamen and their goods were recognised as a particular risk and maritime quarantine was a regular practice. In Italy, quarantine stations called ‘lazarettos’ were built to house incoming passengers, sailors and goods arriving from infected places. The English, however, employed a different system that involved keeping ships at anchor in isolated areas for specific periods of time.

When news of the Marseille plague broke, all ships coming from the Mediterranean were ordered to quarantine for 40 days (in line with the Quarantine Act passed under Queen Anne), and ships heading to the River Thames and River Medway were to be stationed at Stangate Creek and Sharp Fleet Creek or the lower end of the Hope (the part of the Thames between Tilbury and the mouth of the Medway). When it was heard that the ship Satisfaction from Malaga had sailed up the river to Greenwich, Custom House sent officers to order them to immediately withdraw to Stangate Creek to quarantine. Customs officials also called upon the Lords of the Admiralty to station warships at convenient posts to direct all ships coming from the Straits to go directly into Stangate Creek.

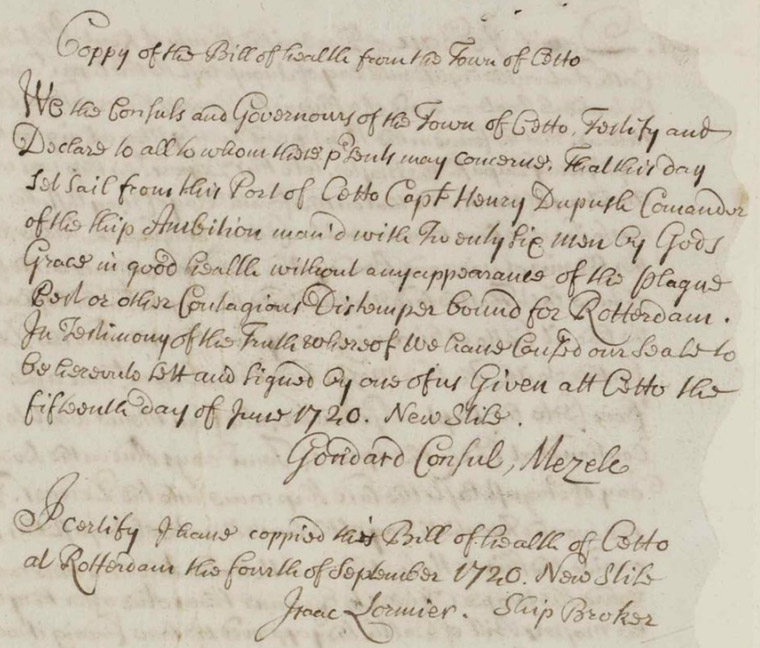

Custom officials played a key role in enforcing quarantine. In the autumn of 1720, customs officials at Deale in Kent complained that they had been refused assistance by the town’s mayor and magistrates when a pilot ‘landed from on board a ship coming from parts infected with the plague’. The pilot had disputed this, explaining the ship had been in Marseille prior to the outbreak of plague and that it had subsequently been issued a clean bill of health from the neighbouring port of Cetto. Customs officials insisted that quarantine was still necessary, but were displeased that they were refused assistance by local officials, who maintained that they had ‘no convenient place on shore to perform Quarantine’. The pilot and three others were eventually quarantined in Sandwich Bay in an open boat. The mayor expressed concern that this was ‘cold and dangerous to their healths’, recommending that either ‘Sandown or Walmor castle (under a mile from town) be used for quarantine if the same should happen again’.

Though it was not just people who needed to quarantine. The goods transported in ships were to be landed, opened and aired for a week in addition to the ship’s 40-day period of quarantine. However, there were a great number of goods that needed to be quarantined even longer. This was because they were considered more susceptible to infection. It was widely held that infected bodies produced poisonous substances and so human or animal products were regarded as particularly dangerous if they had originated from an infected area. This meant that parcels of feathers, fur, hair, wool, and animals skins were particularly suspect.

Of the many petitions that the Privy Council received from ship owners and captains to release their goods, one concerned a parcel of human hair (for wigs) that had been bought in the northern parts of Germany. As this was the product of Germany, the petitioner William Maitland argued that he had bought hair ‘from places which are in perfect health, and at so great a distance from any infected country as cannot be suspected of any infection’ and that he could produce an attestation from ‘the persons who cut the said hair’. The hair was taken to a warehouse in Deptford used for the reception of animal skins and human hair, but it was not to be released until the testimony of the persons who had cut the hair had been received. Fibrous materials such as hemp, flax, and cotton were also considered at risk for absorbing infection, as were the sailors’ clothes and bed linens, which were to be aired on the ships’ deck during the last week of quarantine.

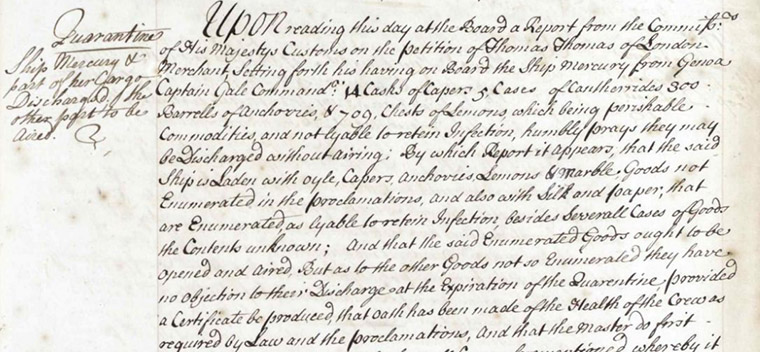

Many ship owners and merchants petitioned to have their goods released following the 40-day quarantine and spared the additional week’s airing, which was especially urgent for perishable goods. The merchant Thomas Thomas argued that the 14 casks of capers, 300 barrels of anchovies and 709 chests of lemons he had imported from Genoa should be discharged without airing, ‘being perishable commodities and not liable to retain infection’.

There are dozens of similar petitions to release other perishable goods, including wine, fruit, and almonds from Malaga; oils, seeds, gums, brandy, and coffee from Livorno; and one instance of 3,520 baskets of raisins transported from Alicante. This was granted in most cases, but was problematic when cargo was also laden with enumerated goods (those identified as susceptible to infection). The Clapham Galley was given permission for its imports of silk, linen and hemp to be spared airing because they were the product of Italy and Sicily, places seemingly uninfected with the plague. The exception was a bale of Turkish silk brought from Symra, which with the carpets, cotton wool, and goats wool had to be opened and aired, ‘being all of the growth of Turkey’.

Some ships weren’t as fortunate. The most explosive case came with the Bristol Merchant and Turkey Merchant, which had loaded cargo from Cyprus at a time it was reportedly affected by plague. It was thought that the non-enumerated goods could not be separated from enumerated goods safely, and that the cotton cargo, in particular, posed such a high risk that three men on the Turkey Merchant had died from handling the material. Ultimately, a committee of Council ordered that the ships and their cargos must be destroyed. Holes were driven into the ships’ decks and flaming tar poured down them to burn the cargo and ship in its entirety. For the ship owners and merchants, the loss was considerable and, in order to prevent any discouragement to current and future traders, it was agreed that the ship owners would be paid compensation.

Public health measures were often a balancing act between protecting lives and livelihoods. Some argued that quarantine measures caused great financial damage to a ‘trading nation’ like Britain, though in the eyes of others, such as the physician Richard Mead, ‘no charges ought to be thought great, which are counterbalanced with the saving a nation from the greatest of calamities’.

This article was originally published in The National Archives

Articles you may also be interested in

The Epidemics of the Middle Ages – Audiobook

THE EPIDEMICS OF THE MIDDLE AGES – AUDIOBOOK By Justus Hecker (1795 – 1850) and John Caius (1510 – 1573) Tanslated by Benjamin G. Babington (1794 – 1866) Justus Friedrich Carl Hecker (1795-1850) was a German physician and medical writer, whose research focused on the history of epidemics, in a broad sense of the term that included pandemics like the […]

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.