Reading time: 5 minutes

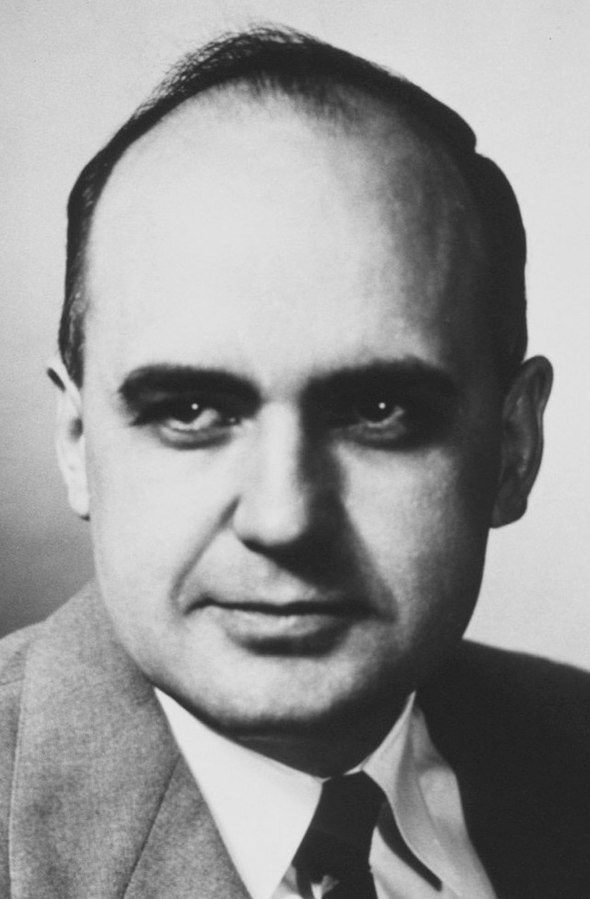

Maurice Hilleman is credited as the man who saved more lives than any other scientist in the 20th century. He developed over 40 vaccines throughout his career, eight of which are still routinely administered today. His intuitiveness prevented the spread of a possible flu pandemic during the 1950s. Despite these lifesaving achievements and the fact that he is widely considered the father of modern vaccines, Maurice Hilleman is not a well-known figure today.

By Madison Moulton

Who was Maurice Hilleman?

Maurice Ralph Hilleman was born on 30 August 1919, during the height of the Spanish Flu. Hilleman worked on his family’s farm during his childhood, where he became comfortable working with chickens. He later credited his success to this work with chickens, as fertile chicken eggs were often used to grow viruses for vaccines from the 1930’s onwards.

Despite his family’s financial issues, Hilleman still managed to attend college with his brother’s help as well as scholarships. He graduated from Montana State University at the top of his class in 1941. Three years later, he graduated from the University of Chicago, where he received his doctoral degree in microbiology. Hilleman’s doctoral thesis on chlamydia infections proved that the disease wasn’t caused by a virus, but rather by bacteria. His discovery ultimately helped doctors better treat this disease.

Hilleman showed incredible aptitude in the field of academia, but he decided to enter into the pharmaceutical industry. He believed that this would allow more people to reap the benefits of his research. Hilleman’s decision went against the wishes of his professors who told him that they don’t ‘train people for the industry’.

His movement away from the traditional path set the stage for his career and management style. Those who knew Hilleman knew him for his dedication to his work, his profanity, and his military-unit style of management. He was considered a forceful, yet modest man, as none of his vaccines were named after him. In an interview, he conceded that he ran into conflict with most people. Despite this, his subordinates were extremely loyal to him.

Hilleman’s Career and Vaccines

After graduating from university, Hilleman began work for the pharmaceutical company E.R. Squibb & Sons (now Bristol-Myers Squibb). He immediately began his research on vaccine development, creating a vaccine against Japanese B encephalitis. This disease infected the brain and at the time threatened Allied soldiers in the Pacific Theatre during WWII. He developed this vaccine within months, saving the lives of thousands of Allied military personnel.

In 1948, Hilleman transferred to the Walter Reed Army Research Institute in Washington DC. Here he studied respiratory diseases and influenza outbreaks. Hilleman later proved that influenza viruses mutate due to genetic changes known as antigenic shifts and antigenic drift. His discovery proved the need for a yearly influenza vaccine.

After nine years, Hilleman joined Merck & Co. where he headed up its virus and cell biology research department. It was here where Hilleman developed the majority of his 40 vaccines.

1957 was also the year that Hilleman recognized that a flu outbreak in Hong Kong could lead to a pandemic. He obtained a sample of the virus and began incubating the disease against antibodies. He found that the majority of people in the United States had no antibodies against this strain of influenza. This further highlighted the threat of this disease.

Hilleman approached several pharmaceutical companies with his samples to develop a vaccine. Despite none of his research yet being reviewed by any of the regulatory agencies, the pharmaceutical companies agreed. His perseverance ensured the creation of 40 million doses of the vaccine, saving millions of lives. The flu killed approximately 116 000 people in the US, and 1.1 million worldwide. Hilleman was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his work.

Mumps Vaccine Development

In 1963, Hilleman’s daughter, Jeryl Lynn, developed the key symptoms of mumps, a sore throat, and swollen jaw. Hilleman immediately cultivated samples from her which later became the basis of his mumps vaccine. In 1966, his younger daughter Kirsten received one of the first doses of his experimental vaccine. A year later, Hilleman licensed his mumps vaccine, which later became part of his MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine.

Maurice Hilleman’s Legacy

By the end of his career, Hilleman and his team developed over 40 vaccines. This includes eight of the 14 vaccines that are still recommended for children today – measles, mumps, hepatitis A and B, chickenpox, meningitis, pneumonia, and Haemophilus influenzae (Hib vaccine).

He later became an adviser for the World Health Organisation, and after retiring, stayed at Merck & Co. as a consultant. He was also an Adjunct Professor of Paediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania until his death.

Hilleman received several awards for his work, including the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1975. In 1988, he was awarded the United States’ highest scientific award, the National Medal of Science. The scientists who followed state that Hilleman was most influential in the field of vaccinology.

Hilleman passed away in April 2005, but his work continues to live on and save lives. Unfortunately, he is still under-recognized for his ground-breaking work and for the number of lives he saved.

Articles you may also like

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.