Reading time: 8 minutes

Eric Neville Lilliebridge was born to Alvine and David Alexander on 16th July 1915 in Narrabri, New South Wales. At the time of Australia’s entry into the war with Germany in September 1939, Eric was a 24-year-old farm labourer. He submitted his application to enlist on 4th November 1939 in Paddington, and, from 5th December 1939, he was officially a member of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF).

Eric joined the 6th Division Signals, which was attached to the 6th Australian Division, part of the 2nd AIF. After approximately 40 days of training in Australia, the unit moved to India and then to the Middle East, where further training was undertaken. Eric became a signalman. Although the rank of signalman was the lowest in the Royal Australian Corps of Signals (equivalent to a private in other army units), it played a crucial role in ensuring effective communication across the battlefield during World War II.

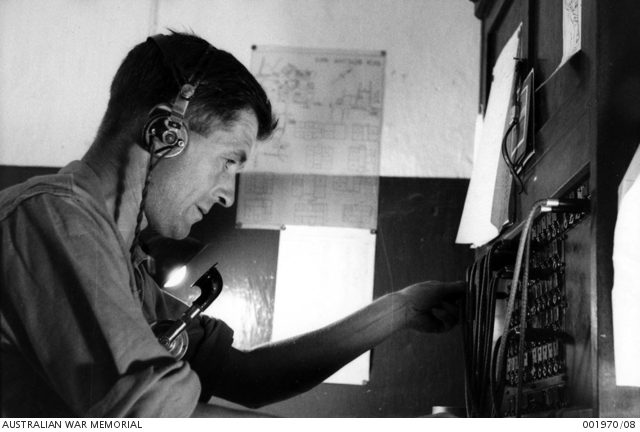

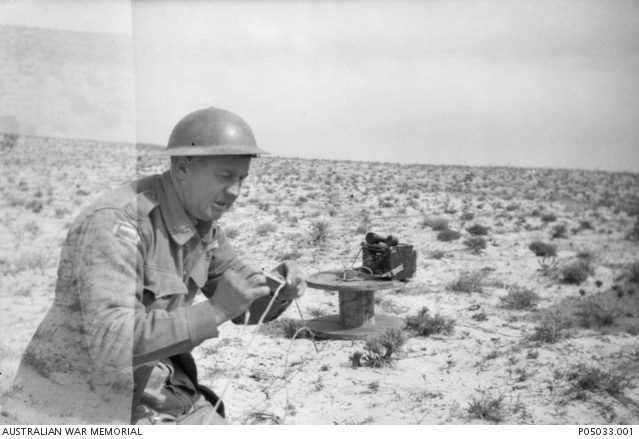

The 6th Division played an important part in the great Allied victories at the Battle of Bardia and the Battle of Tobruk. Signallers predominantly used field telephones, like those shown below, to establish and maintain communications between the units they were attached to. This involved running cable between the units, and then ensuring this cable was repaired if it was cut by enemy action or artillery fire. This could be a very hazardous job, as it involved moving in the open between units, as well as running the risk of encountering the enemy soldiers that had cut the cable!

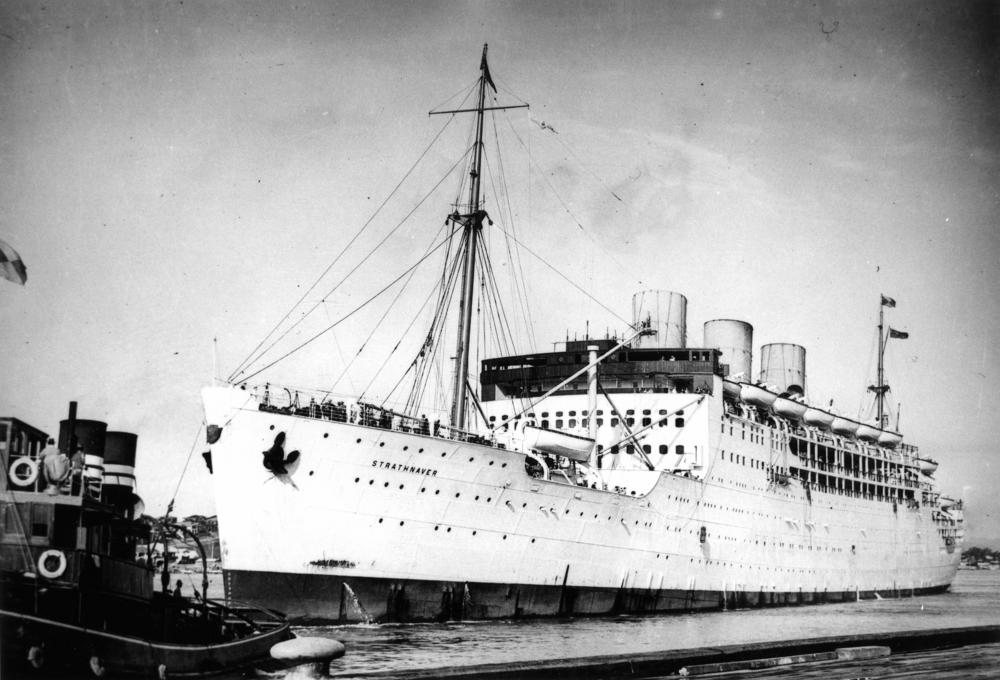

In April 1941, the 6th Division Signals sailed to Greece on the HMT Strathallan, a British passenger ship that had been converted into a troopship. This ship was part of the larger convoy that transported ANZAC troops to Greece.

In Greece Eric was attached to the Headquarters of the 19th Brigade, an Australian unit made up of 2/4th Battalion, 2/8th Battalion and 2/12th Battalion. He moved swiftly to northern Greece to take up defensive positions along the Aliakmon line. As the German invasion pushed the Allied forces back Eric and the 19th Brigade withdrew to the next defensive position at Domokos, just north of Lamia. From here they withdrew further south, under air attack for much of the journey. The Australian forces maintained their cohesion throughout the withdrawal, helped by the continual efforts of the signallers who worked tirelessly to establish radio or field telephone communication links.

Following the withdrawal through Greece the Australians were evacuated to Crete. But this journey was a hazardous one. Eric was onboard the SS Pennland when it was attacked by German bombers and sunk. He, along with many of the 19th Brigade and the 6th Division Signals were rescued by HMS Wryneck, which took them the remainder of the way to Crete.

Crete was then attacked by German airborne troops, and despite fierce resistance from ANZAC, British and local Greek troops, the Germans ultimately captured Crete, though at a heavy cost to their airborne divisions. Eric was probably stationed with the Australian troops defending Rethimno, as this was the area 19th Brigade Headquarters had been assigned responsibility for. This was an intense and hard fought battle. It was during the hectic withdrawal across the island that Eric was captured, on the 29th of May 1941. He was reported missing, listed as a casualty by his unit on 7th June 1941. His family and friends likely learned of the news from the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate on 20th June 1941. The paper reported: “Two extensive A.I.F. casualty lists for New South Wales were released today, predominantly comprising the names of men reported missing. The lists include 344 names, of which 25 are officers—one major, six captains, and 18 lieutenants.” Among the names was that of signalman Eric Neville Lilliebridge.

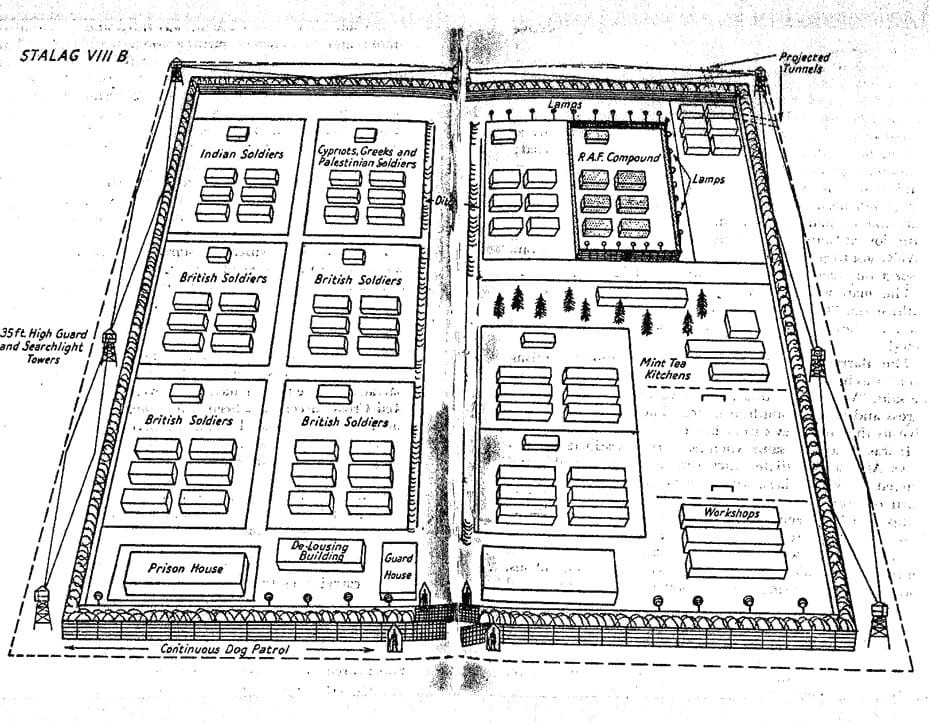

Eric’s unit became aware of his whereabouts some three months later, when he was recorded as a prisoner of war at Kokkina Hospital in mainland Greece. After being treated for malaria, Eric was transferred to Stalag VIII-B, a large German prisoner-of-war (POW) camp near the town of Lamsdorf, in what was then Upper Silesia (now part of Poland, near the town of Łambinowice). This site had a long history of internment, with barracks originally built to house British and French POWs during World War I. It had also served as a detention facility for prisoners of war during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71.

Eric spent almost three years enduring the harsh conditions of this POW camp, which was later renamed Stalag 344, braving overcrowded barracks and hard labour on the camp’s farms. In 1945, he was transferred to Stalag XIII-C , a satellite camp of Stalag VIII-B. In January 1945, as the Red Army advanced, German authorities evacuated the Stalag VIII cluster of camps, forcing thousands of prisoners onto brutal “death marches” through harsh winter conditions marked by extreme cold, insufficient food, and mistreatment. Tragically, most casualties among the POWs occurred during these final days of the war in Europe.

LAWRENCE WILLIAM ARTHUR COLLECTION)

Fortunately, Eric survived this ordeal and was sent to Britain after liberation. He arrived in London in May 1945 and spent his time in the UK recuperating and travelling the countryside. On 31st August, he boarded a ship bound for Australia, and on 5th October 1945, he was finally back where he started—New South Wales. He was honourably discharged on 15th November 1945. By that time, he was 29 years old and had served for 2,137 days, of which 2,096 were spent outside Australia.

In 1947, he married Beryl Mary Brady, also from Narrabri. She has her own story of military service. She was working as a Chemist’s assistant in Sydney when she decided to enlist in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) on the 26th June 1942. She was posted to RAAF Townsville Headquarters and spent the majority of her wartime service there. Townsville was a key forward base for the RAAF supporting operations against the Japanese in New Guinea and the Pacific. It was subject to Japanese air attacks. Beryl excelled in her work as an Office Orderly, being promoted to Corporal and being assigned the specialist role of Recorder.

Eric and Beryl’s son, Philip Lilliebridge, continued the family’s military tradition. He served 30 years with the Australian Army from 1982 to 2011, retiring with the rank of Major.

It is from The North Western Courier, printed on 18th May 1950, that we learn Eric Neville Lilliebridge and his father, David Alexander Lilliebridge, were putting up for auction “the well-known mixed farm ‘Nuabie’”, the very same farm from which Eric had enlisted in a World War, 11 years earlier. Former signalman Eric Neville Lilliebridge passed away on 7th May 1972, aged 57, and was buried at Lincoln Grove Memorial Gardens & Crematorium.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 202

1. Writing in the 1380s, who was the first to refer to Valentines Day on the 14th of February?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

General History Quiz 70

Weekly 10 Question History Quiz.

See how your history knowledge stacks up!

1. Which leader said “We will bury you!”?

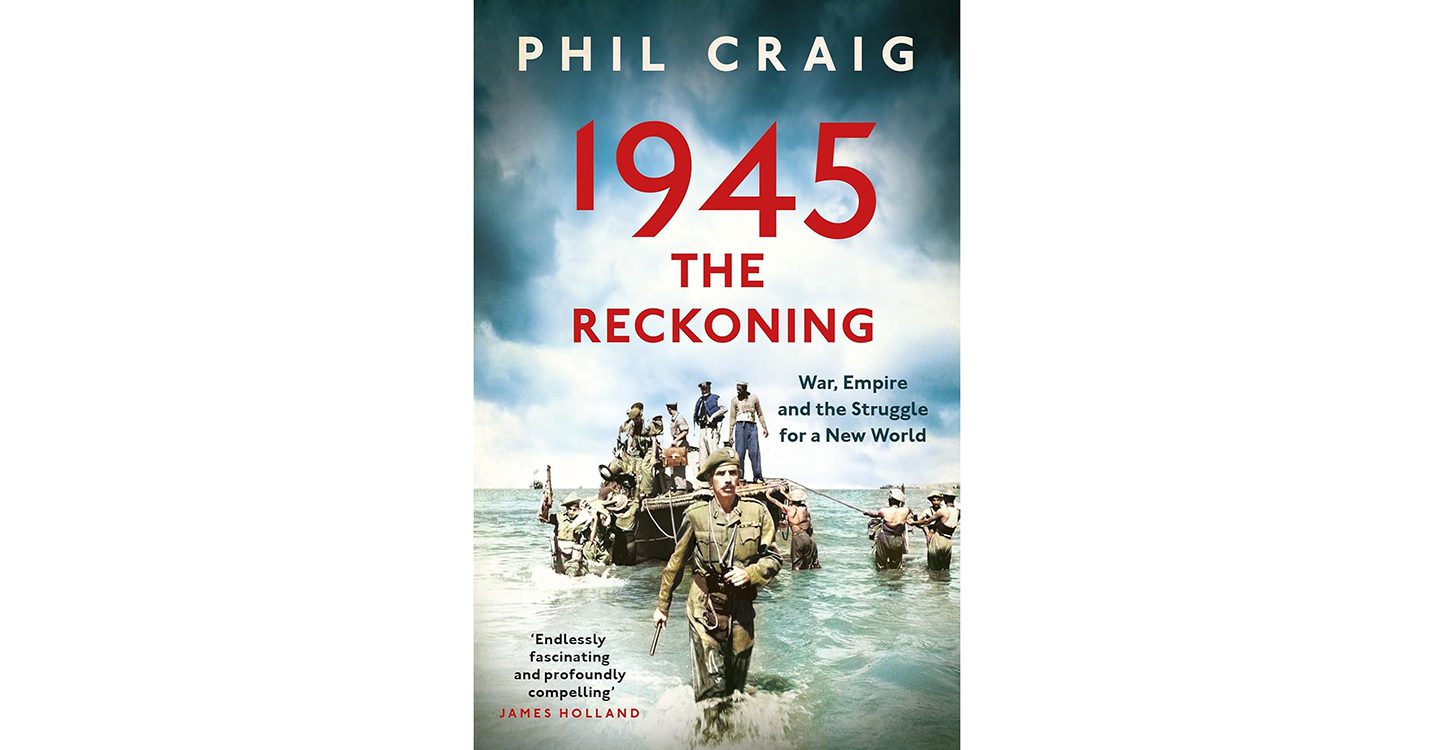

1945: The Reckoning: War, Empire and the Struggle for a New World by Phil Craig

This is a fascinating book, which explores the complexities of the final year of the war from the perspective of a varied range of people who lived through it. This is a book that crosses the globe from Britain to Germany and from India to Indonesia…it is ambitious, deeply thought-provoking and, as with all the […]