Reading time: 14 minutes

From a humble, precarious exile in London, Free France patched together from soldiers and sailors of the scattered French military under the leadership of General Charles de Gaulle. One of the most storied resistance movements in World War II, far-flung Frenchmen swelled in number until hundreds of thousands could return to liberate France in 1944.

By Morgan WR Dunn

But this isn’t the whole story. In fact, the full history of how France came to free itself has only gained wider recognition in recent years, as the role French African troops played in the struggle has become better known.

From 1939 to 1945, hundreds of thousands of men from French colonies in Africa provided desperately-needed strength. Despite institutional racism, often brutal conditions, and sometimes outrageous treatment, these soldiers brought France back from the brink of being a colony itself and would take a hand in shaping the futures of their own homelands.

The Rise of Free France

We are the Africans

Who come from far away,

We come from the colonies

To save the Fatherland

We have all left

Family, huts, homes

And we keep in our hearts

An invincible ardour

For we want to carry high and proud

The beautiful flag of our whole France

And if someone were to touch it,

We would be there to die at his feet

Beat the drums, to our loves,

For the Country, for the Fatherland, die far away

We are the Africans!

“Le Chant des Africains,” French military song, 1941

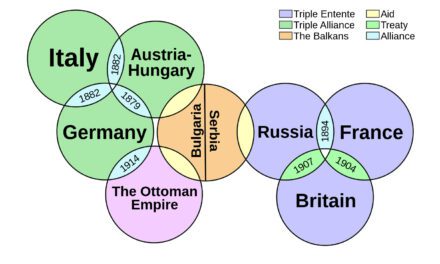

An unprepared France was flung into a battle for its existence when, in April 1940, the German Army flashed across the border. Over 120,000 of the soldiers defending France came not from the Republic, but from its vast colonial empire in Africa and Asia.

After just six weeks of fighting, the French were overwhelmed, and the Third Republic collapsed. Adolf Hitler summoned a French military delegation to surrender at the Glade of the Armistice near the city of Compiègne, the site where the Imperial German Army had surrendered on 11th November 1918.

The terms were harsh. A rump state, headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain and headquartered at the central French spa town of Vichy, was established to avoid the expense of a nationwide occupation, while the expense and risk of forcing France to surrender its fleet and colonies was to be avoided. Marshal Pétain’s French State would officially retain control of its territories in Africa, the Caribbean, and Indochina.

Occupying Germans forced the Vichy military authorities to repatriate African troops to their homes. German troops, reared on the outrage felt at the role of West Africans early in the occupation of the Rhineland after the First World War, as well as a steady diet of Nazi-directed state racism, were furious to be fighting men they considered subhuman, particularly as African Troops often gave them some of the fiercest resistance. In one instance, at the village of Chasselay, German soldiers used two tanks to murder 50 prisoners of war of the 25th Senegalese Tirailleurs Regiment. Locals defied German orders not to bury the bodies.

France couldn’t be beaten so easily, however. A politically opinionated Brigadier General, Charles de Gaulle, had escaped to London a week before the surrender, and on 18th June, he broadcast a speech through the BBC exhorting the French to keep fighting. France, he said, was not alone, with an ally in Britain and “a vast Empire behind her.” Cut off from Metropolitan (i.e., European) France, this empire was now the most valuable resource in the brewing fight to retake his homeland.

The Origins of France’s African Army

France had a toehold in Africa from the early 17th century, but its colonial empire on the continent could truly be said to have begun in 1830, when an army loyal to the French July Monarchy invaded Algiers, sparking a decades-long campaign of conquest and the foundation of a vast regime in North, Central, and West Africa. The invaders quickly found that the French people had no taste for sending young men from the Métropole to die in its new colonies to the south. Moreover, Europeans knew little of the languages, places, and customs of the continent, and they were particularly vulnerable to tropical diseases.

But France still needed soldiers to hold this new empire, and with the homeland hesitant to provide them, they turned to a cheap, effective alternative: Africans themselves. The first regiments of native African infantry, the tirailleurs (derived from the French word meaning “to pull” (as in a trigger; more accurately the term is translated as “skirmisher,” referring to their historical role as light infantry) Senegalais, were raised in Senegal in 1857. Eventually, infantry regiments raised across French Sub-Saharan Africa were given the title “tirailleurs Senegalais,” regardless of which colony they were recruited from.

Rebuilding French Strength

De Gaulle may have been resolute, but he was a general without a nation, let alone an army. To get one, he had to cut into Vichy’s soft tissue.

In October 1940, he sailed south with his small collection of Free French naval, air, and ground units, avoiding Algeria, where his British sponsorship would do him no favours among Vichy leaders still reeling from the Royal Navy’s attack on the French fleet at Mers el Kebir. Instead, he carried on down the coast, first to Dakar in French West Africa (Afrique-Occidentale française, or AOF), which Free French troops, assisted by British and Australian naval forces, failed to take from the Vichy loyalist governor, Pierre Boisson.

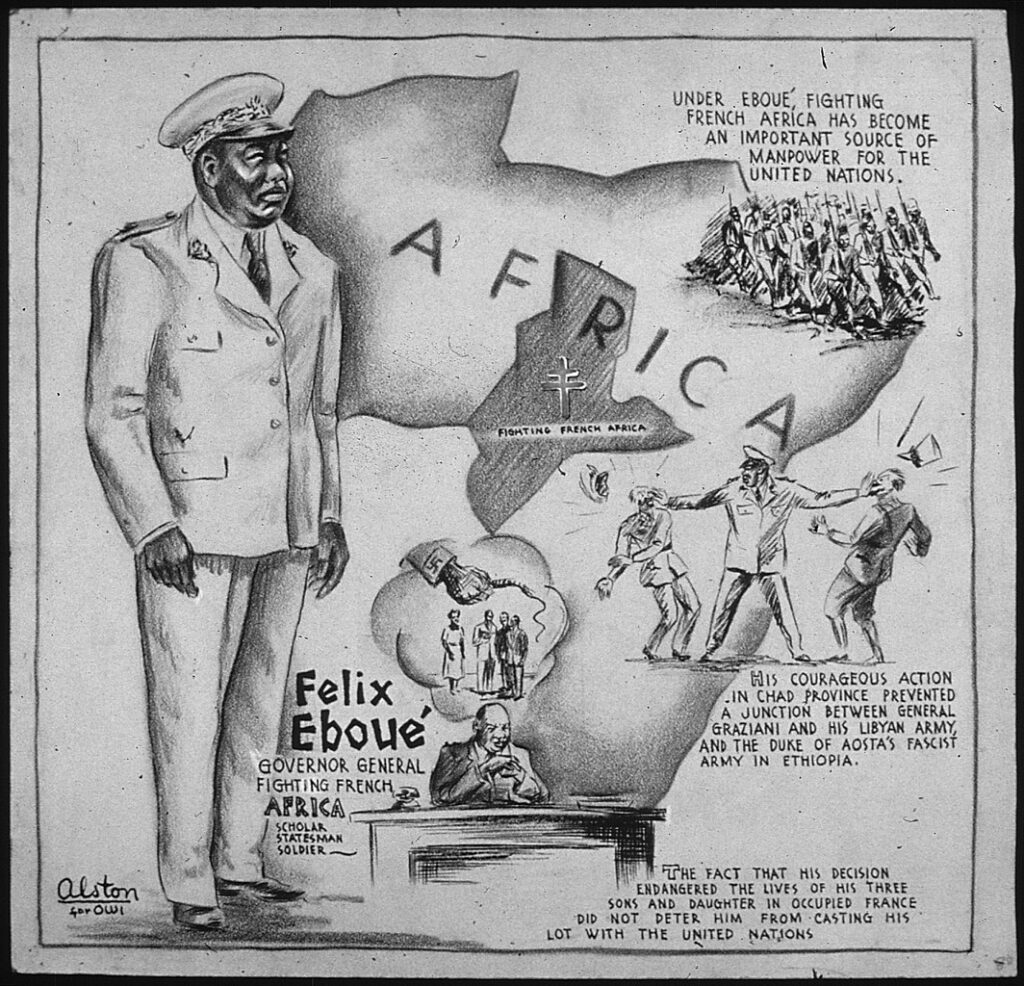

Undaunted, de Gaulle pressed on to French Equatorial Africa (Afrique équatoriale française, or AEF). AEF was France’s most sparsely-populated, poorest, and least important colony, but it contained French Chad, governed by Félix Éboué, a rare example of a black African in a senior leadership role in the colonial empire. Éboué was sympathetic to de Gaulle, and industrious: electing to join Free France in August 1940, he quickly raised 30,000 tirailleurs, a sorely-needed injection of military strength for the minuscule resistance movement.

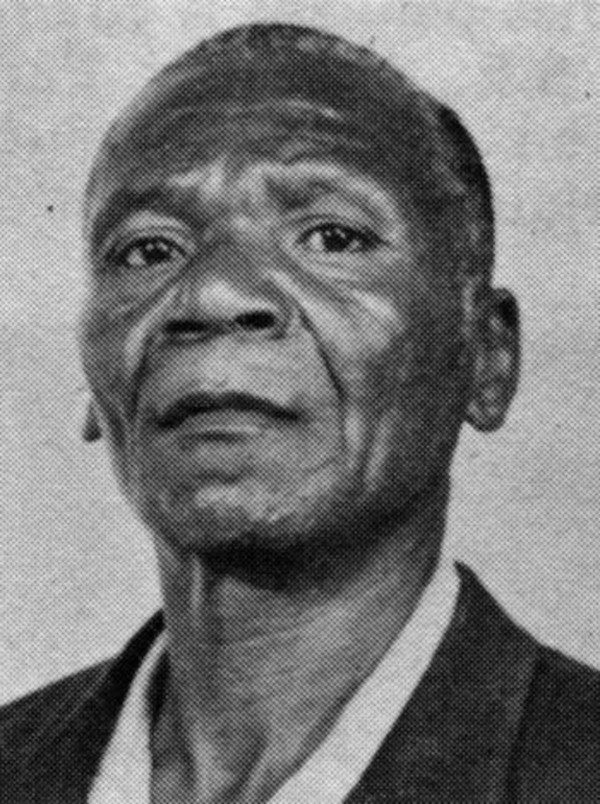

Paul Koudoussaragne, Compagnon de la Libération

Paul Koudoussaragne was just 20 years old when he enlisted in the 2nd Battalion of Tirailleurs of Ubangi-Shari on 8 March 1940. In August, his unit elected to join Free France.

Koudoussaragne, a native of the city of Bimbo in Ubangi-Shari, today’s Central African Republic, was typical of tens of thousands of young men from French-ruled Africa. With Metropolitan France inaccessible, Free France formed the Empire Defense Council in October 1940 to govern the country’s contested overseas empire. It was these territories that contained the largest pool of French manpower outside of France itself in the gloomy early days of the war, and its men, attracted by promises of enlistment bonuses and tax exemption for their families, would fill the ranks of de Gaulle’s armies on the uphill struggle to return.

Equipped with aged French weapons and uniforms, these men were the small foundation of a rebellion. Paul Koudoussaragne, whose regiment was the first to serve Free France and would form the backbone of the Bataillon de marche no 2 (2nd Marching Battalion, BM2) from November 1940, was one of the first to rally to the Cross of Lorraine under the command of General Philippe Leclerc.

1942-43: the Uncertain Years

By the end of August 1940, all four colonies of AEF had rallied to Free France except for Gabon, which reinvigorated Free French forces seized in November. Free France spent 1941 developing an economic base in the liberated AEF and using its African soldiers to attack Italian Libya, and to help topple the Vichy administration in Syria and Lebanon.

1942 saw a sterling example of revived French military strength used to advance the Allied cause. At the end of May, the 4,000 men of the 1st Free French Brigade, made up of Foreign Legionnaires and AEF troops, including Koudoussaragne’s BM2, attacked German and Italian forces near the Libyan village of Bir Hakeim.

Outnumbered by roughly ten to one, French troops succeeded in taking the village, forcing the Axis to extend their supply lines and hastening their defeat during Operation Torch. Koudoussaragne distinguished himself at Bir Hakeim by carrying ammunition to his unit under fire and despite being wounded. For this, he was made a Companion of the Order of Liberation.

The Allied success in North Africa also unlocked the French colonial territories of Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, and Free French forces wasted no time in forming divisions of Algerian and Tunisian tirailleurs, Moroccan goumiers (comparable units given a Turkish-derived title), and spahis (another borrowed Turkish word) of indigenous African cavalry. In 1943, Free French General Henri Giraud and de Gaulle combined their forces to create the French Liberation Army.

Then, in June 1943, Giraud and de Gaulle formalised their combined Free France by creating the French National Liberation Committee, a provisional government deriving legitimacy from its lineage from the Third Republic. The union also prompted French West Africa to rally to Free France, from which another 100,000 soldiers were recruited.

1943 was also the year when the United States’ involvement in the Allied cause first began to pay dividends. American industrial might, fully awakening and retooled for wartime production, began to yield clothing, weapons, vehicles, tools, medicine, and aircraft for its embattled allies. African troops, freshly clad in American uniforms and armed with American weapons, now made up a formidable Allied contingent.

Liberation – But for Whom?

In the North American and Western European mind, Operation Overlord, the 1944 invasion of Normandy signals the beginning of the end for the Nazi war machine. But it was in fact the year before that the Allies began to smash through Axis defences to liberate Europe. The Italian campaign, beginning with Operation Husky in July 1943, involved forces from around the world, including the French Expeditionary Corps, 60% of its strength made up of French North African troops. African troops would also take part in the liberation of Corsica in 1943 and the invasion of Elba, one-time place of exile for Napoleon Bonaparte, in June 1944.

When Overlord was originally planned, it included an accompanying invasion of southern France which was shelved due to a lack of resources. After the invasion, Allied planners realised that the small, damaged ports of northern France would be insufficient to supply their forces, and eyes turned to the south again.

Operation Dragoon, an invasion of the Côte d’Azur, began with landings of United States forces in August 1944. Following them were units like the 3rd Algerian Division and the 9th Colonial Infantry Division, the latter containing several regiments of tirailleurs Senegalais, which liberated the cities of Toulon and Marseille and added intense pressure on German forces, already under pressure from the west and, increasingly, from the Soviet assault in the east. The Vichy puppet state was demolished and its last members exiled to Sigmaringen in Germany.

The French Liberation Army had finally come home. Two thirds of its strength of 550,000 was made up of African troops. These men had fought in Africa, the Middle East, Italy, and France itself. Unreliable postal systems had cut them off from contact with their families, and they’d continued fighting despite the intense confusion of serving two Frances and poor pay (Éboué’s promised bonuses never appeared), bad food, bad equipment, far more bloodshed than any army could be asked to bear, and the racism of many of their own leaders.

In spite of all the hardships and indignities, they’d fought a desperate battle to free their colonial rulers and won – but the hardest burdens, the harshest insults, were yet to come.

Honour and Disgrace

By early August 1944, the Allies had almost reached Paris. De Gaulle insisted that French troops be the first to enter the city, to give France the impression that French soldiers were their liberators. But de Gaulle faced a conundrum: “from the colonial perspective,” writes historian Ruth Ginio, “having African subjects as part of the heroic forces of liberation to which the civilian metropolitan population owed its gratitude was mostly disadvantageous.”

The general believed that seeing African liberators would be demoralising to white French citizens. Accordingly, African troops were forbidden to enter Paris, and a suitable French division, General Philippe Leclerc’s 2nd Armoured Division, would be “whitened” to make it racially acceptable. It was no small task, as there were not enough white French soldiers available (British General Frederick Morgan remarked that, aside from one division in Morocco, “every other French division is only about forty per cent White”), forcing Leclerc to incorporate exiled Spanish Republicans and even Italian prisoners of war into his division.

Even on the day de Gaulle had been dreaming of for four years, as he walked down the Champs-Élysées to a jubilant welcome, he couldn’t escape the fact of how he had got there. Along the way, he was shadowed by Georges Dukson, a Gabonese tirailleur who’d been captured by the Germans after fighting in the Battle of France. After two years in captivity, Dukson had escaped, joined the Resistance, and now followed de Gaulle around the city, his face flashing through photos of the triumphal procession, his bandaged arm in a sling. Dukson, who fought ferociously as a Resistance member in Paris’ 17th arrondissement and earned the nickname “Lion of the 17th,” would be arrested for looting and shot in November, at the age of 22, while trying to escape.

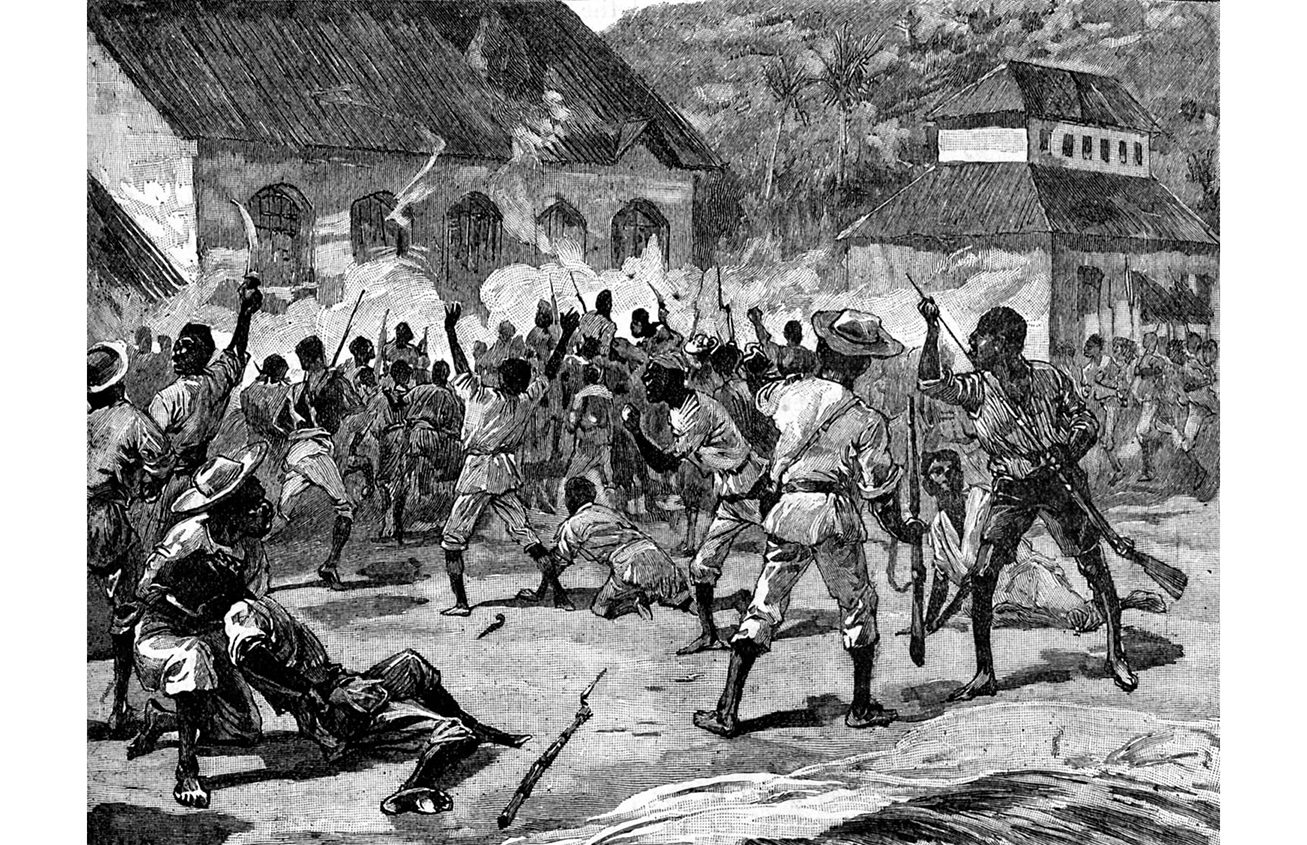

Postwar France was ungrateful to its African defenders. Many returned home to find the promise of tax exemption had been broken, and they were forced to surrender souvenirs and goods they’d purchased abroad. French authorities also didn’t hesitate to use violence to enforce their rule: when tirailleurs at Thiaroye, near Dakar, Senegal, repatriated from German POW camps, demanded back pay and better conditions, as many as 300 were massacred by colonial authorities.

The final insult came with independence. As France’s African colonies gained their own freedom, African veterans’ military pensions were frozen in time, with inflation rapidly outstripping the value of the payments. Only in 2010, after the release of a film, Indigenes (Natives), depicting North African soldiers’ experiences in the war, were pensions finally adjusted.

Even then, French military pension rules required veterans to spend at least six months a year living in France to remain eligible, cutting many of the aging survivors off from their families, a rule only suspended after the release of yet another film, Tirailleurs, in 2023.

Even before the end of the war, the belief (or fiction) that France’s liberation was the work of London-based Free France and the domestic Resistance was widespread, but some knew the truth. Jacques Soustelle, an ethnologist and early member of Free France, wrote in his memoirs,

“With what rage anti-Gaullists of both the left and the right, the Communists and the Vichyites, relentlessly propagate the myth of a London Resistance. To both sides, I counter with the truth: Free France was African.”

Articles you may also like

“IT WON’T DO TO PRETEND THAT WE ARE POWERFUL”: CHINA’S GERMAN-TRAINED ARMY

Reading time: 11 minutes

In 1926, a newly-unified China had millions of men under arms, but few who could wield them effectively. Determined to make the country ready to defend itself, Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek turned to an unusual ally.

For a decade, officers and experts from Germany’s Reichswehr oversaw the transformation of China’s army. While their plans were never fully realised, they had a significant impact on the war to resist Japanese invasion.

Jamaica’s Morant Bay Rebellion and it’s brutal repression

Reading time: 11 minutes

On 12 October 1865, John Davidson, a magistrate in the east of Jamaica, wrote to the island’s Governor, Edward John Eyre:

‘The people at Morant Bay [on the island’s southeast coast, St. Thomas-in-the-East parish] have risen, burnt down the Court-house, released all the prisoners, murdered several white people.’

Hard Fought: Australia In The Mediterranean Theatre 1940-1945 Conference

Reading time: 3 minutes

History Guild is supporting a conference examining the part played by Australian’s in the Mediterranean theatre of WW2. This conference is presented by Military History & Heritage Victoria in Melbourne, Australia on the 9th and 10th of April 2022. It will be held in person and features a conference dinner on the 9th of April. History Guild is subsidising conference registration fees for students and early career researchers. This will allow more history students to study and research this important part of Australian history.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.