Reading time: 13 minutes

There are plenty of video games that use historical backdrops for their narrative, or even entice you to recreate history in some way. As we discuss with historian Pieter van den Heede in our article on whether games can teach history, the question remains of how much you actually learn while playing these games. Thankfully, some do a much better job than others, and in this article, I will explore four of them.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

For this article, I’m going to focus on two types of games. The first are what I’ll call methodical games, where the gameplay focuses on what historians actually do: gather sources and make sense of them. There are a few examples out there, but I chose the games Attentat 1942 and Svoboda 1945, both by Czech studio Charles Games.

The second type is what I’ll call experiential games, which focus on the experience of what it was like to live through certain events. The field is a lot broader here, but I picked two games I thought did a fine job of conveying the terror of living through dark times, the appropriately named Through the Darkest of Times by German studio Paintbucket Games and This War of Mine by Polish developer 11 bit studios.

To be clear, this isn’t a list of the most historically accurate games or even the most entertaining games — though all have a fun factor, of a kind. Instead, these are games you can use to learn something about what the world used to be like, or even to help teach others.

Methodical Games

These games are meant to teach the player how to deal with the most basic thing a historian utilizes in their work: sources. After all, can you trust your sources? Or should you be careful about who and what you believe?

Attentat 1942

On June 4, 1942, shots rang out in Prague, ending the life of Reichsprotektor Reinhard Heydrich. Besides being the “protector” of Bohemia and Moravia — the puppet state created after the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia — he was also one of the main architects of the Holocaust.

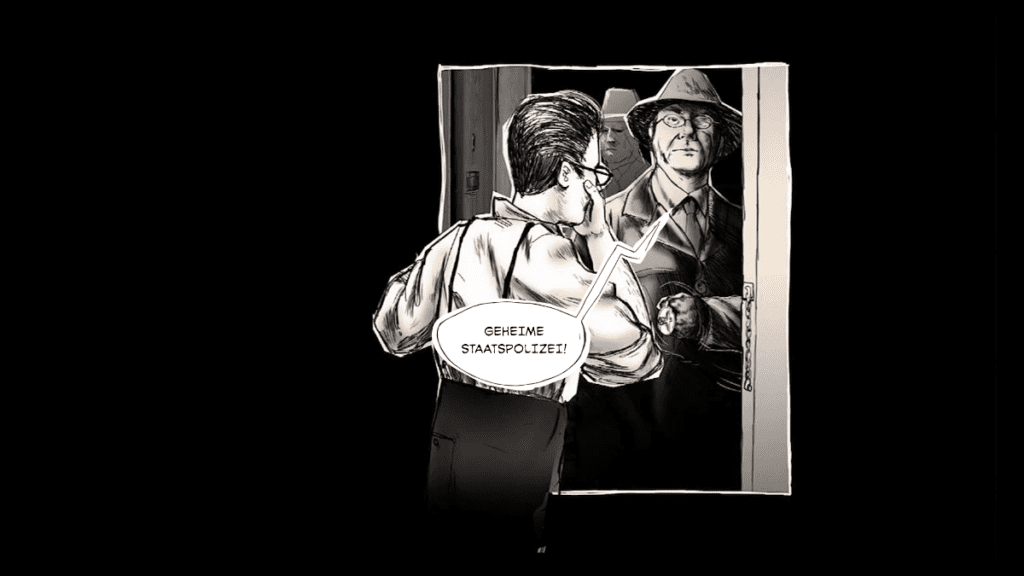

The story of Attentat 1942 picks up as the echoes of the shots are still dying. Your grandfather hears a knock on the door and shadowy men take him away. Though he returns weeks later, it’s unclear what actually happened. Was he involved with the attempt on Heydrich’s life somehow?

This is the question you, the player, are faced with, as sixty years later, your grandfather is dying in hospital. To find out what happened, you’ll speak to several people who knew your granddad at that time. As you go along, you’ll listen to stories about the horrors that so many people lived through, as well as work through the many different threads presented by your interviewees.

Was their neighbor a Gestapo spy, like your grandmother claims? Or was it your granddad who was being paid by the Germans? Who was your grandfather’s mysterious friend, and was he involved in the attack on Heydrich?

You work your way through all these questions in live-action interviews, filmed with real-life actors. You have to be careful what you say, though, as the wrong question can end up with you being thrown out of your interviewee’s apartment. Luckily, you can earn credits to redo these failed interviews by doing well in the mini-games Attentat 1942 breaks up the action with.

At the same time, the mini-games are also a weak point. Though they’re far from bad, they tend to break up the flow of the game. Where the interviews have you sort through the narrative of what happened in the summer of 1942, the games have you deciding what materials in a study might be offensive to the jack-booted thugs about to search your apartment. Although educational, the mismatch between these two activities can be a bit jarring.

Also jarring for some may be that all spoken dialogue is entirely in Czech. The subtitles are excellent, but if you’re not a fan, Attentat 1942 may not be the game for you.

Besides that, Attentat 1942 is a great way to find out how history gets made, with plenty of twists and turns to keep you occupied for the two or three hours it will take you to complete. Other than the stories of your subjects, you can also learn a lot about wartime Czech history through the conversations, as well as the excellent encyclopedia included in the game.

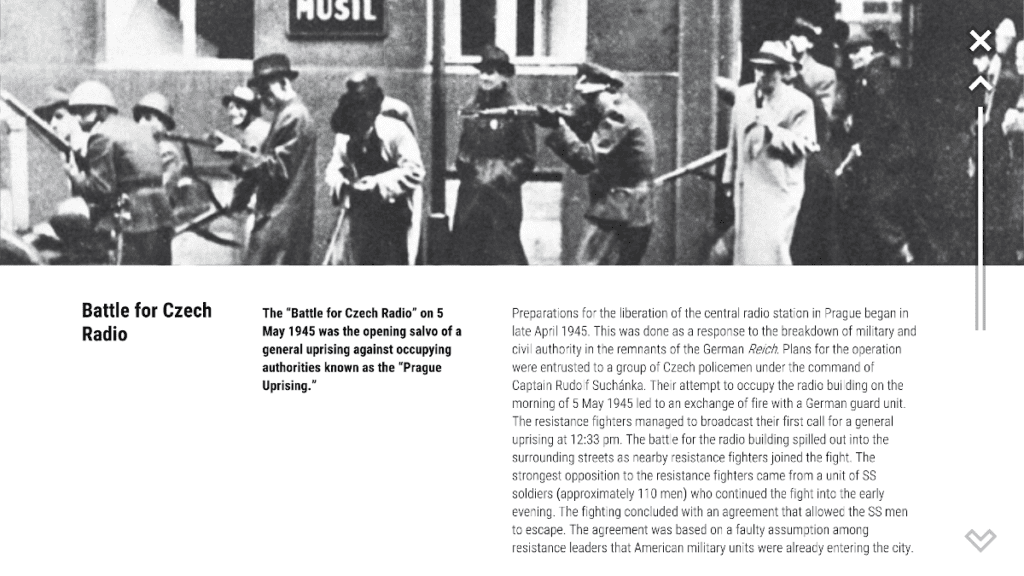

Svoboda 1945

Thanks to the success of Attentat 1942, Charles Games made another game in the same vein called Svoboda 1945. Svoboda means “freedom” or “liberation,” and is also the name of the fictional village where the story is set. As a government official, you’ve been tasked to find out whether an old schoolhouse should be granted monumental status or not.

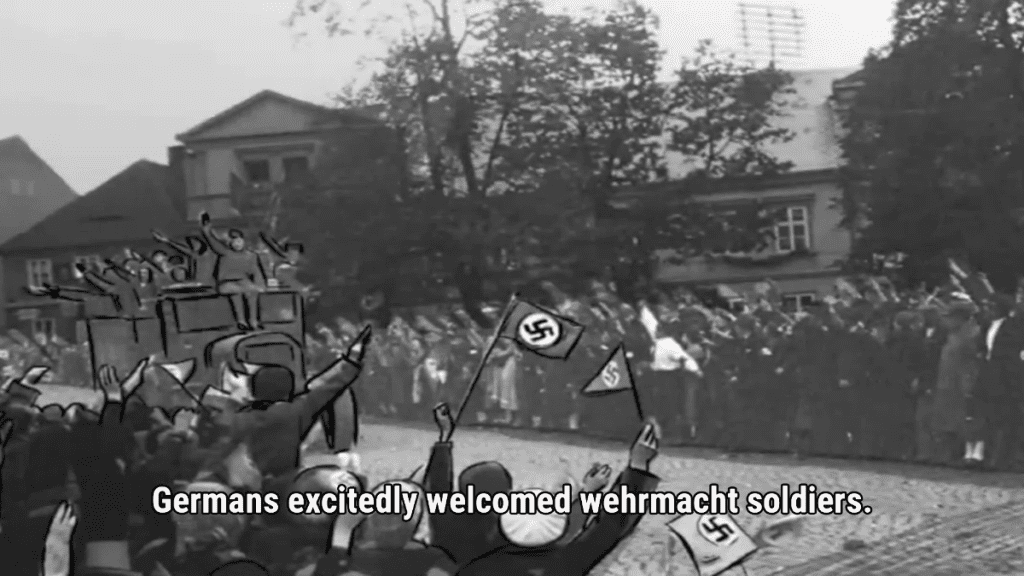

This sets the stage for a story that is smaller in scope than that of Attentat 1942, but at the same time goes a lot deeper. Situated in the Sudetenland, Svoboda was witness to scenes of great joy when the Nazis marched in in 1938 as many of the ethnic Germans greeted them as liberators. The brutality of the occupation left its mark on the Czechs that lived there, though, and they shed few tears when the Germans were deported in 1945 and 1946.

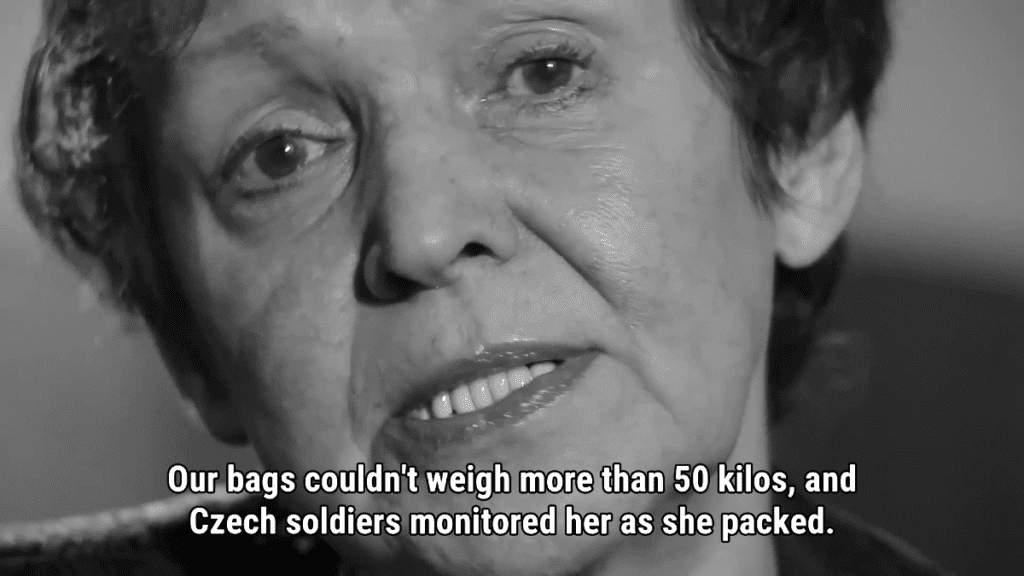

The story of the Sudeten Germans is one of the more morally difficult episodes of the post-war years, and the game handles it deftly. It presents you with the many different viewpoints and lets you, the player, make up your own mind. It doesn’t make it easy for you, however, stacking facts atop facts to make clear that there are no simple answers.

While at first, you may get the sense that the events are portrayed only from the Czech perspective, the many crimes that took place during the expulsions slowly come to light as the game progresses. At the same time, the human factor is rarely left out of the picture, meaning you’re never pulled to one side or the other.

The end result is a tapestry where something new appears every time you look. This is aided by a much stronger focus on the interviews and fewer mini-games. The games also feel more embedded in the story, increasing their value.

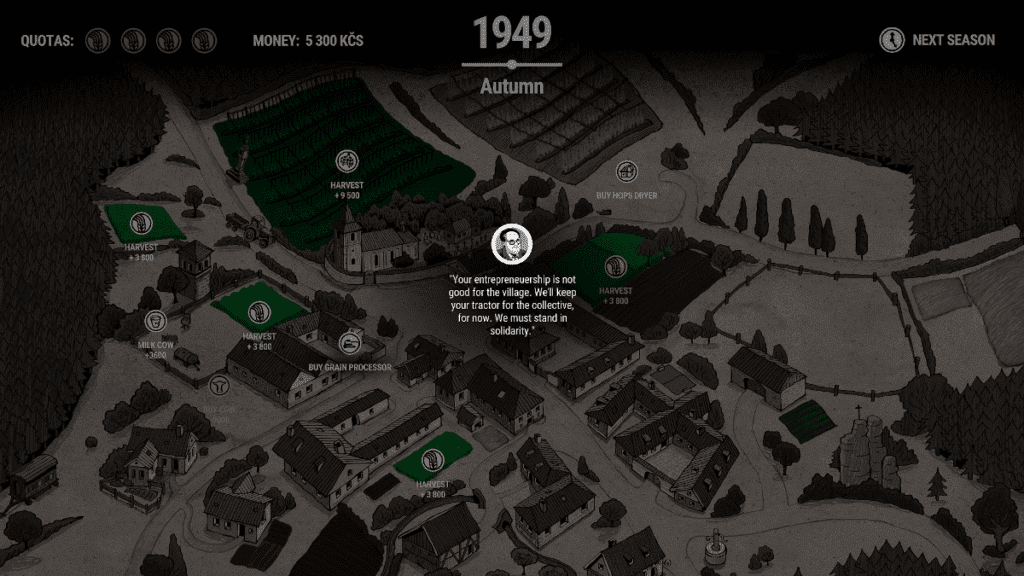

A great example is a game where you play as one of Svoboda’s farmers right after the war ended. You’re tasked with growing your profits and holdings, but as the Communists gain power over the years, this becomes harder and harder. They confiscate your land, your tractors, and raise your quotas. It’s enough to make the game annoying and you’ll probably end up pretty anti-Communist when you finally lose.

In the next scene, another character brings up that much of that farmer’s wealth was probably made by collaborating with the Germans, and that the other farmers in the village suffered from his greed. Every time you think you know something, Svoboda 1945 twists the kaleidoscope; it’s an amazing experience.

Buy Svoboda 1945: Liberation on Steam

Experiential Games

Games as well put together as Attentat 1942 and Svoboda 1945 are rare, not least because developing them must be a massive task. More common are games where some aspect of the past is simulated, but the results are a bit more hit and miss. I picked two I felt did a great job.

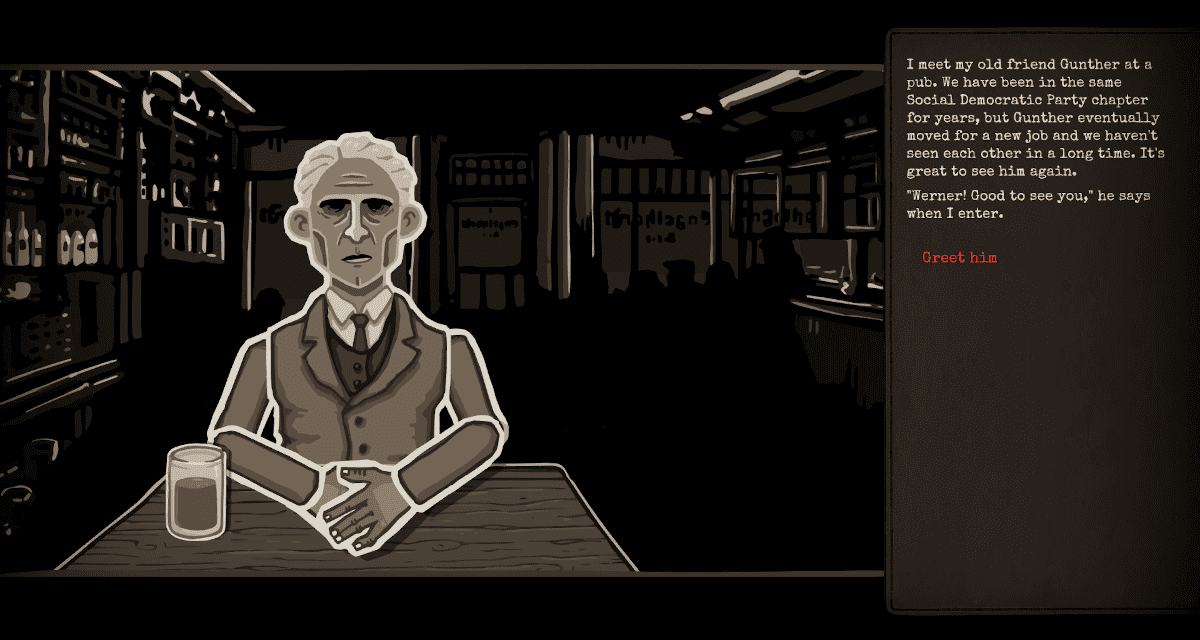

Through the Darkest of Times

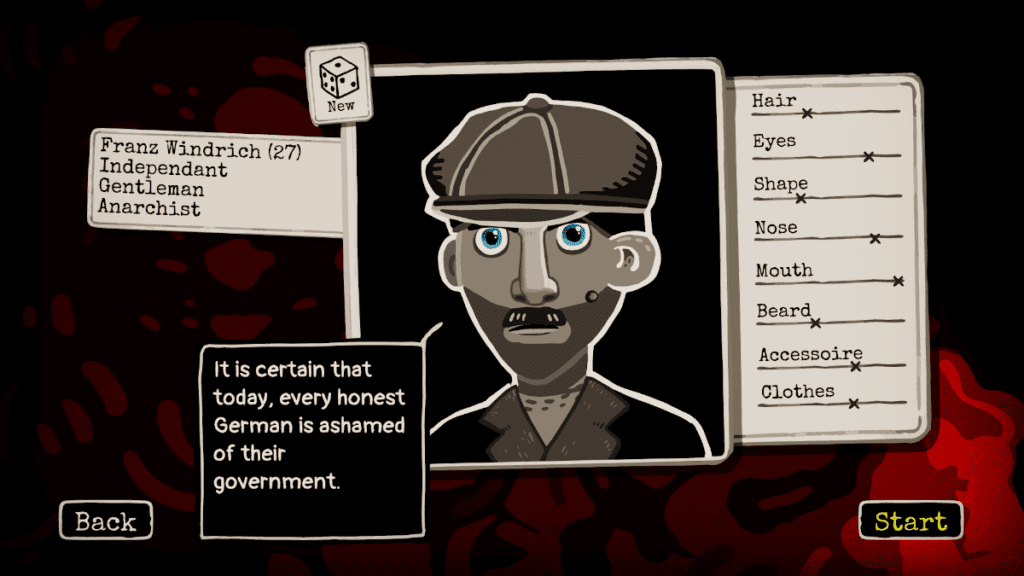

Through the Darkest of Times sheds light on something that has sadly remained unknown to many people: the resistance by ordinary Germans against the Nazi regime. The story starts the day Adolf Hitler wins the German election. You and a few friends decide to resist the new regime in any way possible.

At first, this takes the form of gathering supporters and growing your group of active members and try to raise funds. But before you know it, you’re scrawling anti-regime graffiti on walls, infiltrating the SA, and even sneaking people in and out of concentration camps.

Every turn is a week, and you and your little cell can perform all kinds of actions. From a historical perspective, this is great as it gives you an idea of how hard it is to start a grassroots organization. In the history books, you often get the feeling that resistance explodes spontaneously. Instead, it is the result of hard work by small groups. Through the Darkest of Times understands that at a basic level.

While playing, I found myself wishing the game explained itself better. I played for about an hour, realized I cocked things up and had to start over. This is because many advanced actions require prerequisites, which I had not performed. I feel the game could have explained that with a single dialogue.

Also, the game doesn’t always track who’s who in your cell very well. At one point, we rescue the husband of a cell member, and a few weeks later that same person is celebrating their wedding. It’s clearly just a coding error, but it does make the game feel a bit sloppy.

Despite these flaws, the way the Through the Darkest of Times is put together historically is anything but sloppy. Every week starts with an overview of the news and whatever new atrocities the Nazis have cooked up. This gives you a feeling of impending doom (after all, you kind of know how the game’s story will end) while also showing you how quickly the Nazis consolidated power.

This is also shown in the way your background influences gameplay. If you play a communist, the SA will come to your door the night of the Reichstag fire and beat the daylights out of you. Play as a social democrat, and a former comrade will attempt to persuade you to turn coat and join him in National Socialists.

Through the Darkest of Times is, despite its faults, an amazing game that teaches a lot about how totalitarianism operates and how life is for people that don’t fit in in a state that demands total conformity. It’s a disquieting experience, to say the least.

Buy Through the Darkest of Times on Steam

This War of Mine

The final game in my little roundup is This War of Mine, without a doubt the most well-known of this list. It won multiple prizes thanks to its excellent gameplay and bleak depiction of civilian life in times of war.

This War of Mine is bit of a unique pick for this list, as it’s hard to call it “historical.” Though clearly influenced by the Bosnian War of 1992-1995, especially the Siege of Sarajevo, it doesn’t reference it directly at any point, and there are no encyclopedia entries. However, there is no mistaking some of the game’s locations, or the way that nobody ever mentions sides. Anybody with a weapon is an enemy, and there’s no mention of allegiance.

The reason I picked This War of Mine is because it pulls few punches and really brings home the message that not only is war hell, but that when push comes to shove, many people will do what’s best for themselves. Often when you hear of sieges or other situations where people have been trapped for months, even years, on end, it’s hard to imagine what those people are going through. This War of Mine helps you understand, as much as a game can.

You start the game controlling a small band of survivors who need to make it through a few weeks of hell until an armistice is declared. During the day, you walk around your shelter, a bombed out husk of a building. You build makeshift furniture, cook food, and catch some shuteye. Nighttime is when the action begins. While some members of your group will stay behind and guard the shelter, one will venture into the city to scavenge.

It’s during these forays that you’ll encounter most of what makes This War of Mine the game it is. Some locations are devoid of life and you can pick up materials that will allow you to repair your shelter. Other locations are far from abandoned, and you may find yourself running for your life as your fellow survivors shoot at you, even if all you did was walk up to them.

The game can also take a dark turn during these expeditions, as you can choose to fight back (provided you’re armed) or simply turn cat burglar and rob people of their possessions as soon as their back is turned. You can also decide to be a complete bastard and simply walk into the home of some defenceless old people and simply take whatever you want as they beg you not to.

Before you think This War of Mine is simply some weird nihilism simulator, though, it should be mentioned that there is a lighter side to it. For example, there are plenty of ways in which you can help your fellow man, by sharing food with neighbours, or simply sneaking past people without stealing anything. There’s nothing forcing you to terrorize those unarmed old people, especially if you can manage to grow your own food.

Still, these actions only blunt the edge of the message This War of Mine is trying to bring home: war is a very bad thing, and maybe we shouldn’t be too quick to condemn people to it.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 176

1. How long did the Berlin Wall stand?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.