Reading time: 8 minutes

Documents from a medieval court case give an insight into Ravenser Odd’s emergence from the sea. The people of nearby Grimsby complained to King Edward I that the new island was preventing people coming to Grimsby to trade.

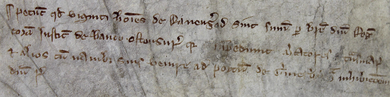

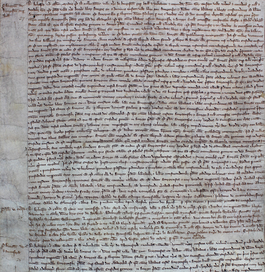

In 1290 there was an investigation into their complaint and the records of that investigation still survive. The people of Grimsby told the king’s investigators that in the time of King Henry III ‘a certain small island was born’, the distance of ‘one tide’ from Grimsby, and fishermen began to dry their nets there. One day a ship was wrecked on the island, and someone made a cabin from the wreckage and began to live there. That man, the first permanent resident of this new land, began to sell food and drink to passing sailors.

Over time, more people began to live on Ravenser Odd and eventually some ships began to stop there to buy and sell goods, as the new island was nearer to the sea than Grimsby. Convenience was not the only reason that merchants stopped at Ravenser Odd rather than Grimsby, though, as the investigation suggests that the people of Grimsby were not paying fair prices for fish.

The investigation led to a court case in the following year at the Court of King’s Bench, the most senior criminal court in England. The people of Grimsby repeated their complaint, saying that they were suffering and could not pay their taxes because the new island was arresting merchants and compelling them to go to Ravenser Odd rather than Grimsby.

Unfortunately for the people of Grimsby, the king’s court was not interested in their local trade dispute. The court ruled that the island of Ravenser Odd had not done anything that went against the king’s peace and so the people of Grimsby had to pay a fine for making a false claim. Ravenser Odd had won the day.

Becoming a borough

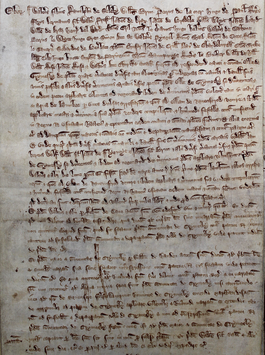

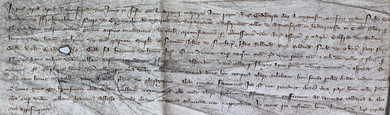

After their victory in court, the people of Ravenser Odd pressed their advantage and petitioned the king to be made a borough. Becoming a borough would give the town a range of advantages, including managing their own local justice, the ability to leave land and property to whoever they wanted, and the right to hold markets and an annual fair.

On 1 April 1299, King Edward I granted their request, issuing them a charter confirming their new rights and responsibilities. Ravenser Odd shares this birthday with a much more well-known borough in the present, Kingston-upon-Hull, whose charter is copied immediately above Ravenser Odd’s in The National Archives’ record.

Piracy and war

Having won their court case and become a borough, Ravenser Odd embarked upon a prosperous and slightly criminal half century. Complaints flooded in from foreign nobles and merchants about the island’s behaviour. Among others, the King of Norway accused the people of the island of stealing goods from a shipwreck and a German merchant complained that the master of his ship had been killed and its goods stolen. There are repeated mentions of the island in the patent rolls, the records of public expressions of the king’s will, asking the islanders to stop extorting money from foreign merchants.

The island also assisted the crown. Ravenser Odd took part in England’s 14th-century wars with Scotland, sending ships to join the naval forces of both Edward II and Edward III. As part of their responsibilities as a borough, they also returned townspeople to parliaments across the 14th century.

The island’s destruction

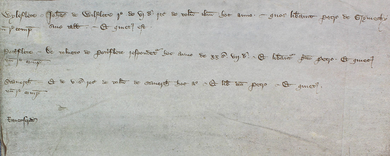

Even in the early 1300s, there were signs that all was not well on Ravenser Odd. The sea had already begun to reclaim the island. In 1329, the king granted the town quayage, the ability to collect and keep money from ships docking in their harbour, to repair their quay that had been damaged by the sea. Quayage for the same purpose was granted again in 1333, 1335, 1340, 1344 and 1347, suggesting that any repairs that the townspeople made were not lasting long.

By 1343, the town was in dire straits. The king wrote to local officials asking them to conduct an inquisition to see if the people of Ravenser Odd could continue to pay their taxes, as he had heard that many houses had been washed away by the sea. In 1346, he repeated his request, saying that the town was greatly impoverished and many of the inhabitants had left as living there continued to become more dangerous.

The inquisition took place in 1346, and confirmed the king’s information about the town’s poor condition. At this point only a third of the townspeople remained on the island, and ‘two parts’ of the town had been washed away by the sea. In the Close Rolls of the following year, the king reduced the town’s tax burden, saying that 145 buildings belonging to one woman had been destroyed, along with many other buildings and 42 plots of land.

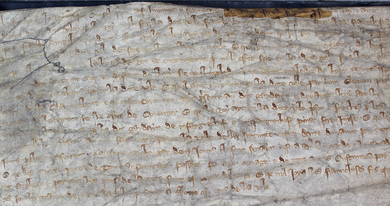

The Meaux Abbey Chronicle, a history of a local abbey, recorded the island’s destruction in graphic terms. In its records of the period 1349–1353, the chronicle states that floods had destroyed the foundations of the chapel on Ravenser Odd and the bodies of the dead had been washed out of their graves. This destruction, the chronicler argues, was a punishment from God for the islanders’ evildoing and piracy.

A manorial account in 1355 includes Ravenser Odd but the island has nothing written next to it in the record – just a blank page. By 1359, an inquisition into the property of a deceased inhabitant of Ravenser Odd said that the town had been ‘completely annihilated’ by the sea.

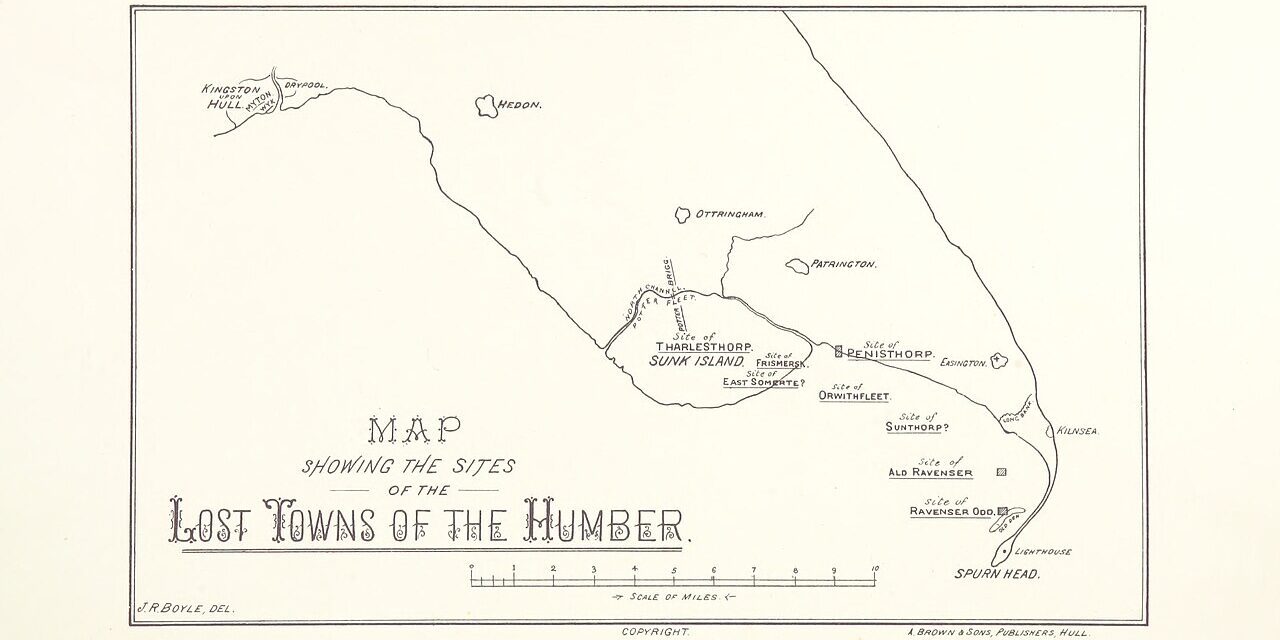

As this 1734 map of the Humber makes clear, Ravenser Odd had disappeared without a trace. Without the records at The National Archives, it would not be possible to piece together its fascinating story.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about Ravenser Odd

Articles you may also like

The First World War continues: Medina, Arabia, January 1919

Reading time: 6 minutes

or many in the West, the First World War in the Middle East was a sideshow to the Western Front. The story of the wartime siege of Medina is even less well-known. But in the region it is still debated and contested, for example in December 2017 when the Foreign Minister of the United Arab Emirates accused Fakhri Pasha of stealing items from Medina, which earned a strong rebuke from the President of Turkey. The First World War in the Middle East had a profound effect on the region, with consequences to this day.

Lemnos and Gallipoli Revealed – Podcast

Over the course of 1915, most of the 50,000 Australian personnel who served at Gallipoli passed through the island of Lemnos. Centring his attention on the Australian experience of the island, historian Jim Claven shares unique and humanising insights into the Gallipoli campaign.

General History Quiz 40

The History Guild Weekly History Quiz.See how your history knowledge stacks up. If you would like an invite to future history quizzes please enter your details below. Subscribe * indicates required Email Address * First Name Last Name History Guild Weekly History Quiz Weekly New History Articles and News Monthly History Guild Update Please leave […]

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.