Reading time: 4 minutes

The 16th and 17th centuries were a notably litigious period in British history. New rights, wealth and obligations had to be protected through legal transactions – and that needed documentation.

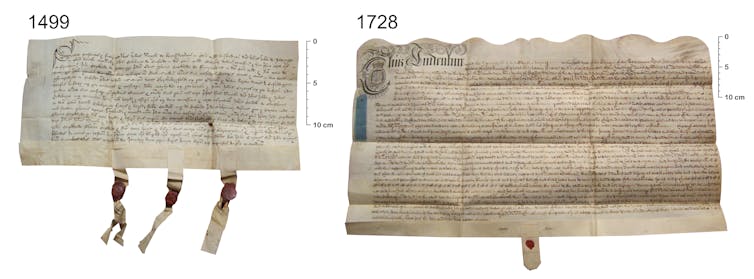

Such was the importance of deeds – legal documents concerning the ownership of property – that lawyers chose to write on parchment, made from animal skin, despite the widespread use of paper. This continued a tradition that stretched back to at least the 13th century.

By Sean Doherty and Jonathan Finch (University of York)

In a new study, we looked at hundreds of examples of parchment to work out which animal skins were used to make them. We found almost all of the samples were made from sheepskin.

The origin of this practice may lie in early efforts to prevent fraudulent changes to legal agreements after they’d been signed, thanks to the unique structure of sheepskin.

Visually identifying the species used to make a piece of parchment is challenging. Diagnostic fibres and follicle patterns are removed when parchment is produced. This means legal deeds are often catalogued as “vellum” (usually meaning calfskin), “parchment” (typically reserved for sheep or goatskin) or even more generally as “animal membrane”.

A technique called peptide mass fingerprinting offers a new way to identify the species, by analysing proteins from the skin. Using this method, we examined 645 documents dated from 1499 to 1969, and found 96.4% of these were sheepskin.

Delamination

Parchment is made from the dermis, a layer of skin which is divided into two parts. There’s the fine dermal fibres of the upper papillary dermis and the larger fibres of the lower reticular dermis. In sheepskin, the interface of these two layers is weak because of an abrupt change in structure and a large quantity of fat, which forms at the junction.

During the production of parchment, the skin is submerged in an alkaline solution which draws out this fat. In sheepskin, which has more fat than cow or goat skin, this process has the potential to leave voids between the two layers. If the surface of the parchment is scraped in an effort to remove or alter text, these two layers are likely to detach – known as “delamination” – leaving a large blemish on the surface.

The risk of delamination is far greater in sheepskin than those of other animals typically used for parchment. Cutaneous fat accounts for as much as 30% to 50% of the dry weight of sheepskin, compared to just 2% to 3% in calf skin and 3% to 10% in goat skin.

This tendency of sheepskin to delaminate was recognised as being of benefit to legal documents as early as the 12th century. In a document called Dialogus de Scaccario, the Lord Treasurer Richard FitzNeal instructed scribes to use sheepskin “for they do not easily yield to erasure without the blemish being apparent”.

Later, in the 17th century, Sir Edward Coke – lord chief justice of the King’s bench – again noted the necessity of writing deeds on durable material such as parchment, “for the writing on these is least liable to alterations or corruption”.

More sheep than people

These anti-fraud properties were undoubtedly a factor in the early adoption of sheepskin for legal documents. But the continuation of this tradition into the late 19th century was likely influenced by their greater availability and lower cost than calfskin vellum.

While sheepskins of any age can be used for parchment, only those from calves younger than around six weeks can be used for vellum, due to their increasing thickness. Only a few hundred thousand skins would have been available annually to parchment makers.

In contrast, the UK was home to more sheep than humans until the Victorian era. The limited supply of calf skin meant that vellum was more than double the price of sheep skin parchment, and was reserved for particularly important documents such as record copies of acts of parliament.

Parchment was also more durable than paper, matching the intended durability of the agreement written on them. For common legal documents, sheepskin parchment presented the ideal inexpensive, durable and fraud-proof material.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 142

1. L’Anse aux Meadows is an important archaeological site from which culture?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Weekly History Quiz No.266

1. Which Empire operated the Manila Galleon trade?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.